I came across a couple of interesting pieces in the last week that had me thinking about the past, present and future of American cities again. After reading them, I felt somewhat upbeat and validated, but also concerned.

The first piece was a research paper by the Brookings Institution's William H. Frey. Frey, a senior fellow for the Brookings Metro research program, conducted an analysis of U.S. Census American Community Survey population estimates for metro areas between 2020 and 2023. He found that large metro areas (those with more than one million residents) have seen a rebound since the peak Covid pandemic period in 2020-21.

According to Frey:

“(t)his includes reduced out-migration and smaller population losses in major metropolitan areas such as New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, as well as shifts from sharp losses to gains in urban core areas such as San Francisco and Washington, D.C. While natural increase (the excess of births minus deaths) has improved almost everywhere, changing domestic migration patterns and especially a rise in international migration served to benefit population change in large metropolitan areas and their urban core counties.”

That’s great news for people who may have thought the so-called "urban doom loop" was an existential threat to American cities. I’d like to be on record as saying the urban doom loop phenomenon was overblown, because cities had adaptive and experiential advantages that would always make them attractive. Adaptive, in the sense that our largest and oldest cities have generally gone through multiple phases of development in their histories. Experiential, in the sense that cities increasingly have the economic and social infrastructure that appeals to today’s global movers and shakers. Good news for the nation’s biggest metro areas.

Unfortunately, the news is not so good as the places get smaller. Frey’s analysis includes a review of annual growth rates for small (with between 50,000 and one million residents) as well as non-metro areas (fewer than 50,000 residents) between 2010-11 and 2022-23. Smaller metro areas saw a boost in growth rates beginning in 2019-20, at the expense of the largest metros. That boost leveled off during the 2020-21, 2021-22 and 2022-23 periods, as larger metros rebounded. Non-metro areas, places with fewer than 50,000 residents, followed a similar trajectory as did smaller metros. However, overall they did not fare as well, because they were already witnessing population loss or minimal growth at the start of the analysis period.

Another trend was noted in the analysis as well. Generally, larger metros rely heavily on immigration and natural increase for population growth, and far less on domestic in-migration. Smaller metros and non-metro areas rely heavily on domestic in-migration for population growth, and far less on immigration or natural increase. That gap widens as places get smaller. The trend was accelerated during the peak pandemic years but appears to be returning to previous levels. But, in a nation with falling birth rates and a increasing reliance on international immigration to fuel economic as well as population growth, what does this means for smaller metros and even smaller non-metro places?

Read the rest of this piece at The Corner Side Yard. (now at Substack)

Pete Saunders is a writer and researcher whose work focuses on urbanism and public policy. Pete has been the editor/publisher of the Corner Side Yard, an urbanist blog, since 2012. Pete is also an urban affairs contributor to Forbes Magazine's online platform. Pete's writings have been published widely in traditional and internet media outlets, including the feature article in the December 2018 issue of Planning Magazine. Pete has more than twenty years' experience in planning, economic development, and community development, with stops in the public, private and non-profit sectors. He lives in Chicago.

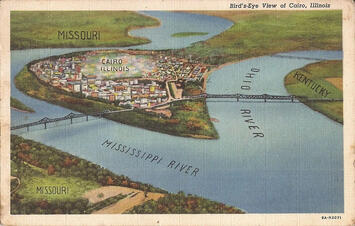

Photo: Postcard depiction of Cairo, Illinois, circa 1940.