The New York Times reported on July 4 that 239 scientists in 32 countries had signed an Open Letter to the World Health Organization (WHO) outlining “the evidence showing that smaller particles can infect people, and are calling for the agency to revise its recommendations.” The letter was published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, co-authored by Lidia Morawska (Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane) and Donald K. Milton (University of Maryland) under the title “It is Time to Address Airborne Transmission of COVID-19” and was signed by 239 others (view/download a PDF copy of letter here).

According to Vox.com, WHO had “maintained that airborne transmission was unlikely to occur outside the hospital setting, where some procedures can generate super-small particles that linger in the air longer than large respiratory drops.”

According to MIT’s Technology Review the “signatories of the Open Letter say the organization is underestimating the role of airborne transmission, where much smaller droplets (called aerosols) stay suspended in the air. These aerosols can travel farther than droplets and linger in an area even when an infected person has left.”

Comments on WHO Position and Response

When the Open Letter was released, WHO had come under criticism for its position on airborne infection.

The scientists wrote: “We are concerned that the lack of recognition of the risk of airborne transmission of COVID-19 and the lack of clear recommendations on the control measures against the airborne virus will have significant consequences: people may think that they are fully protected by adhering to the current recommendations, but in fact, additional airborne interventions are needed for further reduction of infection risk.”

According to The New York Times “interviews with nearly 20 scientists — including a dozen WHO consultants and several members of the committee that crafted the guidance — and internal emails paint a picture of an organization that, despite good intentions, is out of step with science.”

Dr. Linsey Marr, virus airborne transmission expert Virginia Tech told The Times that “WHO also is relying on a dated definition of airborne transmission.”

Within a few days of the Open Letter release, WHO responded that “Short-range aerosol transmission, particularly in specific indoor locations, such as crowded and inadequately ventilated spaces over a prolonged period of time with infected persons cannot be ruled out.”

Ventilation in Enclosed Spaces, Crowding and Exposure Duration

According to the Open Letter: “Studies by the signatories and other scientists have demonstrated beyond any reasonable doubt that viruses are released during exhalation, talking, and coughing in microdroplets small enough to remain aloft in air and pose a risk of exposure at distances beyond 1 to 2 m from an infected individual.”

Noting that WHO and other public health organizations “do not recognize airborne transmission except for aerosol-generating procedures performed in healthcare settings,” the scientists express doubt about the sufficiency of current social distancing and hand washing recommendations, “Hand washing and social distancing are appropriate, but in our view, insufficient to provide protection from virus-carrying respiratory microdroplets released into the air by infected people.”

The authors found:“This problem is especially acute in indoor or enclosed environments, particularly those that are crowded and have inadequate ventilation relative to the number of occupants and extended exposure periods.”

Reducing the Airborne Transmission Risk

The Open Letter proposed the following measures to mitigate airborne transmission risk:

- Provide sufficient and effective ventilation (supply clean outdoor air, minimize recirculating air) particularly in public buildings, workplace environments, schools, hospitals, and aged care homes.

- Supplement general ventilation with airborne infection controls such as local exhaust, high efficiency air filtration, and germicidal ultraviolet lights.

- Avoid overcrowding, particularly in public transport and public buildings.

The Open Letter suggests that: “Such measures are practical and often can be easily implemented; many are not costly. For example, simple steps such as opening both doors and windows can dramatically increase air flow rates in many buildings.”

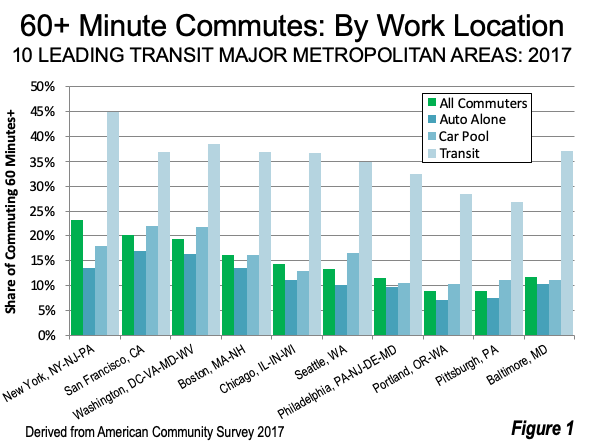

At the same time, providing sufficient ventilation in enclosed environments can be difficult, especially in higher density areas that are typically associated with more situations of overcrowding. At the most basic level, many high rise office buildings packed with employees have windows that do not open. Beyond that, improving ventilation can require major capital and operational expenses. Lengthened elevator wait times could make daily work trips even longer for commuters traveling more than 60 minutes each way and are more than twice as likely to take transit than drive alone (Figure 1).

Already, efforts to address overcrowding have led to mass transit ridership reductions well below the level that a transit dependent urban core must rely upon.For example, daily New York subway and commuter rail ridership (Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North Railroad) is languishing at more than 75% below its pre-Covid levels.

Minimizing the potential for airborne transmission of the COVID-19 virus is essential, not only for the present crisis. This requires not only social distancing but also sufficient ventilation in enclosed spaces. As Open Letter co-author Lidia Morawska told Vox. “If Covid-19 is in indoor air, we should also be doing something about the air.”

Over the coming months, these findings will shape the debate about how to adjust to the pandemic and the ensuing era shaped by it, and also potentially new infections. The challenges will be particularly difficult in higher density urbanization, with which much overcrowding is associated, including offices, factories, warehouses, stores, residences as well as transit vehicles and stations around the world.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a founding senior fellow at the Urban Reform Institute, Houston and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is co-author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Mayor Tom Bradley appointed him to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (1977-1985) and Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council, to complete the unexpired term of New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman (1999-2002). He is author of War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life and Toward More Prosperous Cities: A Framing Essay on Urban Areas, Transport, Planning and the Dimensions of Sustainability.

Photo: United Nations Building, New York via Wikimedia under CC 3.0 License.