Advances in information technology have made it possible to provide estimates of job access by transportation mode in metropolitan areas. The University of Minnesota’s Accessibility Observatory has positioned itself as the leader in this field.

Data for the average metropolitan area resident is now available for 2019 for 50 of the largest US metropolitan areas for autos and transit. A 30-minute standard has been generally adopted for comparing metropolitan areas. This is similar to the average one-way work trip travel time in the United States, which was 27.6 minutes in 2019, according to the American Community Survey.

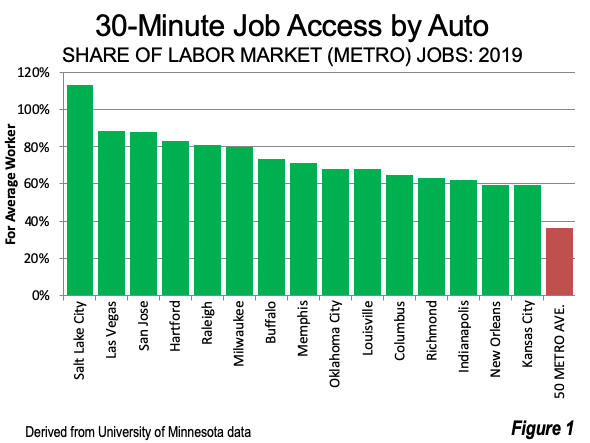

Best Auto 30-Minute Job Access

The best auto access is in metro Salt Lake City (Figure 1), where about 114% of the metropolitan area’s jobs are accessible to the average resident worker. This may seem impossible, but favorable employment geography is responsible. The urban core of Salt Lake City, which includes not only downtown but also the highest densities in the metro area and Temple Square is about five miles south of the Ogden metropolitan area line (Davis County), This makes it possible for Salt Lake City residents to reach jobs in the two adjacent metropolitan areas. Not only is there continuous urbanization to the north, the area along Interstate 15 to the Provo metropolitan area (Utah County) also provides nearby employment opportunities for Salt Lake City metro workers. The employment in these two adjacent metros is nearly as large as that of metro Salt Lake City.

Five more metropolitan areas have 30-minute job access of 80% or more, Las Vegas, San Jose, Hartford, Raleigh and Milwaukee. San Jose’s 88% figure is especially impressive given its location in the traffic clogged San Francisco Bay Area. Like Salt Lake City, San Jose residents benefit from access to the adjacent San Francisco metropolitan area and the jobs-rich, dispersed Silicon Valley extension into San Mateo County.

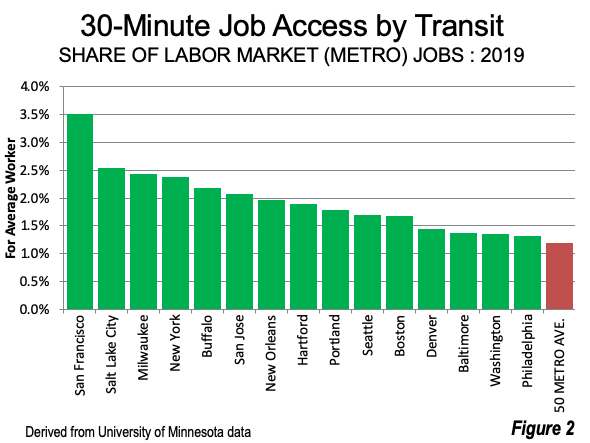

Best Transit 30-Minute Job Access

The best 30-minute transit job access is in the San Francisco metropolitan area, at 3.51% (Figure 2). This compares to the 29.1% of San Francisco metropolitan area jobs that can be reached by autos in 30 minutes, 8.3 times (830%) that of transit.

Salt Lake City ranks second in 30-minute transit access, at 2.54%, followed by Milwaukee at 2.43%. Milwaukee is not surprising, because in my days of chairing American Public Transit Association committees (1980s), Milwaukee was often referred to as a particularly good transit city.

Perhaps surprisingly, New York, which dominates US transit ridership and has by far the most comprehensive transit system in the nation ranks only fourth in 30-minute transit job access, at 2.39%.

The city of New York accounts for about one-half of the jobs in the metropolitan area. The transit market share is 32% in the metropolitan area --- no other metro reaches even 20%. Transit carries 58% of commuters to jobs in the city, but less than six percent of the equally large number of jobs outside the city.

Even so, 30-minute transit access within the urban core is impressive. This can be illustrated by data from the Center for Neighborhood Technology’s alltransit.cnt.org website. Transit 30-minute job access in the city of New York is about four times that of the metropolitan area. And within Manhattan (New York County) transit 30-minute job access for the average resident worker is about 107%. CNT ‘s 30-minute access criteria differ from that of the University of Minnesota. The CNT figure is more than three times as high for the New York metropolitan area, presumably reflecting more liberal criteria).

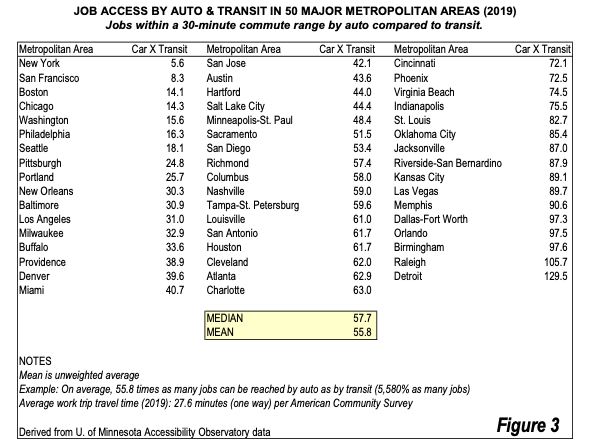

Comparing Auto and Transit 30-Minute Access

Overall, the unweighted average number of jobs accessible by car in 30 minutes in the 50metropolitan areas is 55.8 times that of transit (cars can reach 5,580% as many jobs as transit). The median is somewhat higher, at 57.7 jobs accessible by cars for each job accessible by transit. This ranges from New York, where autos can provide 5.6 times the 30-minute access of transit, to Detroit, where autos provide nearly 130 times the access.

The number of jobs accessible in 30 minutes by auto times those accessible by transit is indicated in Figure 3.

Improving 30-Minute Job Access: The Opportunity for Transit

For more than one-half century, metropolitan areas have pursued the objective of attracting drivers from their cars. Yet in 2019another record was set for driving alone to work (119.2 million daily), This is up from 111.5 million just in 2014, an increase of 7.7 million (American Community Survey data). This is about the same as the total daily transit commuting in 2014 (7.8 million).

Transit’s limited 30-minute job access relative to the auto probably the principal issue behind this. As former principal planner of the World Bank Alain Bertaud put it, if commuting were faster by transit “…drivers would have switched modes already.” It is notable that the seven metropolitan areas with the best transit 30-minute job access also have the seven largest central business districts (downtowns) measured by employment --- the six with transit legacy cities, New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Boston and Washington plus Seattle. These municipalities, as opposed to their much larger metropolitan areas, account for about 50% of the transit commuting destinations in the United States.

It is virtually impossible for transit to close the gap with autos. On the other hand, transit resources should be used most effectively and the access metrics available today make that possible. Maximizing job access, especially in low-income areas where automobile availability is limited could not only improve transit ridership but also reduce poverty. For people without cars, transit’s limited access provides considerable disincentives for working, especially, for example, by single parents needing to make child-care arrangements (For an analysis of 30-minute job access in metro Seattle, see here).

Post Pandemic: 30-Minute Job Access Should Improve

Critically these data are all pre-pandemic. It is likely that remote working will substantially increase as the nation returns to normal. Jose Maria Barrero (Instituto Tecnologico Autonomo de Mexico) Nicholas Bloom (Stanford University) and Steven J. Davis (University of Chicago) report survey data to the effect that 20% of full workdays will be from home after the pandemic. This is more than three times the 2019 level of 5.8%, as reported by the American Community Survey. This would reduce traffic flows and improve work trip travel times (a phenomenon documented in the latest Texas A&M Transportation Institute 2021 Urban Mobility Report). The benefits would be substantial. Not only would workers have more time for leisure or other preferred activities, but 30-minute job access would be improved, with gains to be expected in economic production and poverty reduction.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a founding senior fellow at the Urban Reform Institute, Houston, a Senior Fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy in Winnipeg and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is co-author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Mayor Tom Bradley appointed him to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (1977-1985) and Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council, to complete the unexpired term of New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman (1999-2002). He is author of War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life and Toward More Prosperous Cities: A Framing Essay on Urban Areas, Transport, Planning and the Dimensions of Sustainability.

Photo credit: New York, Lower Manhattan (middle), downtown Brooklyn (bottom) and Exchange Place in Jersey City (top), by author.