Without a great deal of thought put into it, most urban observers can rattle off what can be considered a reasonable life cycle for neighborhoods – a growth phase, a stable peak or plateau, a period of decline, a phase of accelerated decline, then ultimately a chance at renewal. It’s a familiar pattern, not unlike the four seasons most of us experience every year. What distinguishes cycles in neighborhoods within and between cities is usually the height of their growth phases, the depths of their declines, and the overall duration of all cycles.

But Black urban neighborhoods in American cities seem to have a life cycle all of their own. The process in Black neighborhoods deserves keen understanding.

First of all, I think it’s important to note that the life cycle of Black neighborhoods usually starts well before any Black residents live in them. Indeed, in my view the growth phase of neighborhoods has almost always taken place without Black involvement. Historically the housing and commercial infrastructure of urban neighborhoods were created to appeal to specific market segments – working class laborers, office and administrative workers, upper middle class professionals. Such neighborhoods often had an immigrant or native component to them. However in 19th and 20th century America, that did not include Blacks, unless segregated areas were purposely developed to exclude Blacks from other parts of a city. Blacks have rarely gotten in on the ground floor of neighborhood growth.

After a certain period neighborhoods reach a level of stability. Whether they’re comprised of small workingmen’s cottages, walkup apartments or spacious homes, they reach a point when they’ve maximized their growth potential and the focus shifts toward maintenance. How long a neighborhood remains at this stable phase depends on who is permitted to live within it. There are neighborhoods that have been relatively stable for a half-century or more, because they continually appeal to and attract a market segment fairly consistent to what was attracted to it in its early days. But it’s often at this point that Black residents move in. But reactions to our arrival disrupts the trajectory of the cycle.

The Great Migration saw millions of Blacks move from rural locations in the South to urban neighborhoods across the nation. They were seeking the economic opportunity presented to them by the promise of well-paying manufacturing jobs, but they were also seeking the social opportunity to escape racial violence and dehumanizing second-class citizenship in the Jim Crow South. The economic importance of Blacks at the time was recognizable. But White society in Northern cities wasn’t any more interested in integration than their Southern peers.

Swift Transition

That created the “vacuum” – the White flight that precedes Black neighborhood residency, and continues to occur as Black neighborhood residency expands. This happens when a neighborhood reaches its peak, but there’s an uncertainty among White residents as to how long it will stay at that level. If White residents believe their stability is threatened, they’ll move – whether the move is viewed as a lure to greener pastures, or an outside force that compels them to do so.

My parents bought their first house, in Detroit, in the summer of 1968. I was almost four years old at the time and my sister was coming up on her first birthday. The house was a two-story, three-bedroom, one-bath brick Colonial style built in 1950. Probably about 1,800 square feet in size, with a half-finished basement. It was located on a 50-foot wide lot in a solid single-family residential neighborhood on the city’s Northwest Side. It’s still there.

Our house was one of maybe twenty on our Manor Street block. My parents told me we were the fourth, maybe fifth, Black family to move onto the block. If I remember correctly, they bought the house from another Black family that owned it for maybe five years or so. Being just short of four at the time I don’t recall many details, but I vaguely remember a White family living next door to us with a son about my age. I don’t remember any other White families from that time. What I do know is that by the time I started first grade two years later, there were no more White families on the block to remember, with only one elderly White couple across the street that remained through the ‘70s.

Read the rest of this piece at Corner Side Yard Blog

Pete Saunders is a writer and researcher whose work focuses on urbanism and public policy. Pete has been the editor/publisher of the Corner Side Yard, an urbanist blog, since 2012. Pete is also an urban affairs contributor to Forbes Magazine's online platform. Pete's writings have been published widely in traditional and internet media outlets, including the feature article in the December 2018 issue of Planning Magazine. Pete has more than twenty years' experience in planning, economic development, and community development, with stops in the public, private and non-profit sectors. He lives in Chicago.

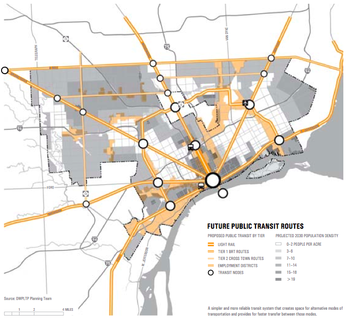

Graph: Proposed public transit routes identified in the Detroit Future City Strategic Framework, a 50-year comprehensive plan, which came out in 2013. Of particular note are the 2030 density estimates made by the planners: the huge uncolored areas northeast and northwest of downtown were projected to have a density of 0-2 persons per acre, indicating near abandonment. Source: detroitology.com