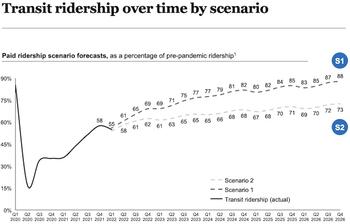

In November 2020, a report from McKinsey & Co. to the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority predicted that transit ridership would recover to as high as 92 percent of pre-pandemic levels by 2025. Now McKinsey has revised that number downward to as low as 70 percent. Even that is probably optimistic considering that recent data indicate that New York subway ridership has been flat at least since February 2022, and has even declined somewhat since June.

More than in most cities, transit in New York depends on fare revenues. Before the pandemic, fares covered more than half the operating costs of New York City transit but only about a quarter of the costs elsewhere. A decline in ridership hits the city’s transit budget harder than almost anywhere else, so it’s no surprise that both national and local media are focused on the “fiscal cliff” that MTA is likely to hurdle over when it runs out of federal COVID relief funds, probably in 2024.

As the New York state comptroller noted in a recent publication, this is more than just a question of increased subsidies vs. reduced service. Instead, it is truly an existential issue for transit agencies nationwide.

Although transit agencies all over the country are quietly lobbying for tax increases to fund them despite low ridership, they are getting push back. The governor of Arizona vetoed such a tax increase for Phoenix transit early this month. The Central Ohio Transit Authority had proposed a ballot measure to increase taxes to support Columbus transit, but dropped it from the ballot when it was clear there was no support.

Meanwhile, transit crime is up 53 percent. Due to driver shortages and poor maintenance, transit has become increasingly unreliable. Having shut down the nuclear power plant that once provided much of New York City’s electricity, New York transit will probably be producing far more greenhouse gases per passenger-mile than many private automobiles, which was already true for almost all other transit agencies.

Given these and other factors, why would anyone want to ride transit? About the only answer many transit agencies have to this question is, “Let’s make it free!” Of course, that will require even more subsidies.

Instead of asking, “How do we fund transit when ridership is down by 60 percent from pre-pandemic levels?” voters and politicians need to ask, “Why should we continue to fund transit when ridership is down by 60 percent from pre-pandemic levels?” There is no good answer to this question.

This piece first appeared at The Antiplanner.

Randal O'Toole, the Antiplanner, is a policy analyst with nearly 50 years of experience reviewing transportation and land-use plans and the author of The Best-Laid Plans: How Government Planning Harms Your Quality of Life, Your Pocketbook, and Your Future.

Chart image: In McKinsey’s study, scenario S1 assumes people will steadily return to working in offices while the much more likely S2 assumes many will continue to work at home at least three days a week. Neither is good news for New York City transit but S2 is particularly bad, especially since even it is probably optimistic.