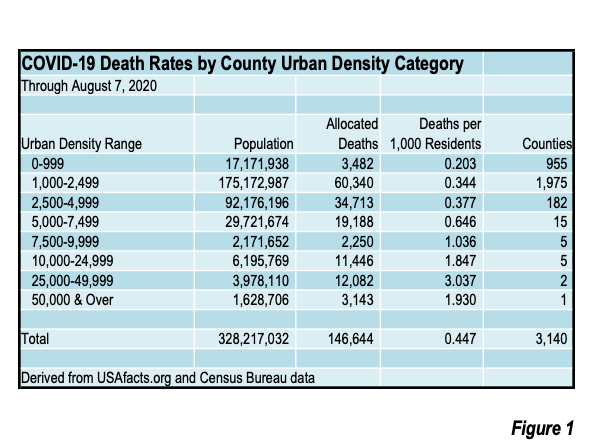

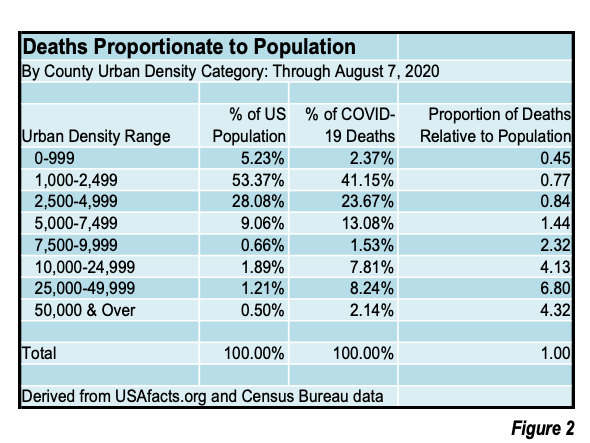

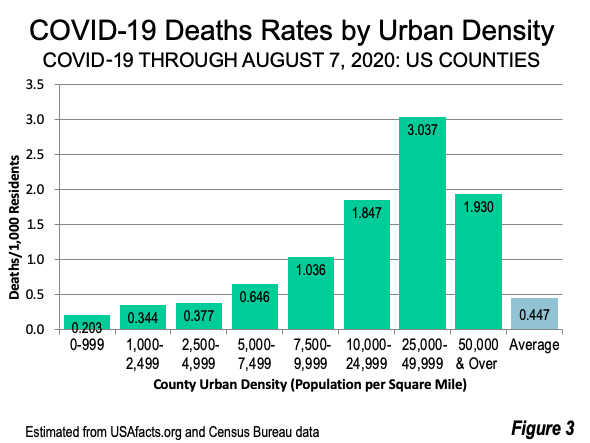

The Figures below provide an update through August 7, 2020 to the relationship between county urban densities and COVID-19 death rates. The data continues to show a strong association between higher urban densities and death rates. The analysis approach and method are described in “Perspective: US Covid-19 Deaths and Urban Population Density.” See: Figure 1: “COVID-19 Death Rates by County Urban Density Category” and Figure 2: “Deaths Proportionate to Population” and Figure 3: “COVID-19 Death Rates by Urban Density.”

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a founding senior fellow at the Urban Reform Institute, Houston and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is co-author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Mayor Tom Bradley appointed him to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission (1977-1985) and Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich appointed him to the Amtrak Reform Council, to complete the unexpired term of New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman (1999-2002). He is author of War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life and Toward More Prosperous Cities: A Framing Essay on Urban Areas, Transport, Planning and the Dimensions of Sustainability.