Globalization, technology, productivity improvements, and the resulting restructuring of the world economy have led to fundamental changes that have destroyed the old paradigms of doing business. Whether these changes are on the whole good or bad, or who or what is responsible for bringing them into being, they simply are. Most cities, regions, and US states have extremely limited leverage in this marketplace and thus to a great extent are market takers more than market makers. They have to adapt to new realities, but a lack of willingness to face up to the truth, combined with geo-political conditions, mean this has seldom been done.

Three of those new realities are:

1. The primacy of metropolitan regions as economic units, and the associated requirement of minimum competitive scale. It is mostly major metropolitan areas, those with 1-1.5 million or more people, that have best adapted to the new economy. Outside of the sparsely populated Great Plains, smaller areas have tended to struggle unless they have a unique asset such as a major state university. Even the worst performing large metros like Detroit and Cleveland have a lot of economic strength and assets behind them (e.g., the Cleveland Clinic) while smaller places like Youngstown and Flint have also gotten pounded yet have far fewer reasons for optimism. Many new economy industries require more skills than the old. People with these skills are most attracted to bigger cities where there are dense labor markets and enough scale to support items ranging from a major airport to amenities that are needed to compete.

2. States are not singular economic units. This follows straightforwardly from the first point. As a mix of various sized urban and rural areas, regions of states have widely varying degrees of economic success and potential for the future. Their policy needs are radically different so the one size fit all nature of government rules make state policy a difficult instrument to get right. Additionally, many major metropolitan areas that are economic units cross state borders.

3. Many communities may never come back, and many laid-off workers may never be employed again. Realistically, many smaller post-industrial cities are unlikely to ever again by economically dynamic no matter what we do. And lost in the debate over the n-th extension of emergency unemployment benefits is the painful reality that for some workers, especially older workers laid off from manufacturing jobs, there’s no realistic prospect of employment at more than near minimum wage if that. As Richard Longworth put it in Caught in the Middle, “The dirty little secret of Midwest manufacturing is that many workers are high school dropouts, uneducated, some virtually illiterate. They could build refrigerators, sure. But they are totally unqualified for any job other than the ones they just lost.” This doesn’t even get to the big drug problems in many of these places. This isn’t everybody, but there are too many people who fall into that bucket.

I want to explore these truths and potential state policy responses using the case study of Indiana. An article in last week’s Indianapolis Business Journal sets the stage. Called “State lags city with science, tech jobs” it notes how metropolitan Indianapolis has been booming when it comes to so-called STEM jobs (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math). Its growth rate ranked 9th in the country in study of large metro areas. However, the rest of Indiana has lagged badly:

Indiana for more than a decade has blown away the national average when it comes to adding high-tech jobs. But outside the Indianapolis metro area, there isn’t much cause for celebration.

Careers in science, technology, engineering and math—typically referred to as STEM fields—have surged in growth compared to other careers in Marion and Hamilton counties. It’s a boon for economic development, considering the workers earn average wages almost twice as high as all others, and employers sorely need the skills. Dozens of initiatives focus on building STEM jobs in the state.

A recent report ranked the Indianapolis-Carmel metro area ninth in the country in STEM jobs growth since the tech bubble burst in 2001. But while the metro area has grown, the rest of Indiana has barely budged from the early 2000s, an IBJ analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics found.

Indianapolis grew its STEM job base by 39% since 2001 while the rest of the state grew by only 10% (only 6% if you exclude healthcare jobs). Much of the state actually lost STEM jobs.

This divergence between metropolitan Indianapolis (along with those smaller regions blessed with a unique asset like Bloomington (Indiana University), Lafayette (Purdue University) and Columbus (Cummins Engine)) and the rest of the state is a well-worn story by now. Here are a few baseline statistics that tell the tale.

| Item | Metro Indianapolis | Rest of Indiana |

| Population Growth (2000-2012) | 15.9% | 4.1% |

| Job Growth (2000-2012) | 5.9% | -7.2% |

| GDP Per Capita (2012) | $50,981 | $34,076 |

| College Degree Attainment (2012) | 32.1% | 20.1% |

Additionally, there does appear to be something of a brain drain phenomenon, only it’s not brains leaving the state, it’s people with degrees moving from outstate Indiana to Indianapolis. From 2000-2010 a net of about 51,000 moved from elsewhere in Indiana to metro Indianapolis. As Mark Schill put it in the IBJ:

“Indianapolis is somewhat of a sponge city for the whole region,” said Mark Schill, vice president of research at Praxis Strategy Group, an economic development consultant in North Dakota.

The situation in Indiana, Schill said, is common throughout the United States: States with one large city typically see their engineers, scientists and other high-tech workers flock to the urban areas from smaller towns.

Even I find it very surprising that of my high school classmates with college degrees, half of them live in Indianapolis – this from a tiny rural school along the Ohio River in far Southern Indiana near Louisville, KY.

What has Indiana’s policy response been to this to date? I would suggest that the response has been to a) adjust statewide policy levers to do everything possible to reflate the economy of the “rest of Indiana” while b) making subtle tweaks attempt to rebalance economic growth away from Indianapolis.

On the statewide policy levers, the state government has moved to imposed a one size fits all, least common denominator approach to services. The state centralized many functions in a recent tax reform. It also has aggressively downsized government, which now has the fewest employees since the 1970s. Tax caps, a comparative lack of home rule powers, and an aggressive state Department of Local Government Finance have combined to severely curtail local spending as well. Gov. Pence took office seeking to cut the state’s income tax rate by 10% (he got 5%), and now wants to eliminate the personal property tax on business. Indiana also passed right to work legislation.

I call this “the best house on a bad block strategy.” I think Mitch Daniels looked around at Illinois, Ohio, and Michigan and said, “I know how to beat these guys.” Indiana is not as business friendly as places like Texas or Tennessee, but the idea was to position itself to capture a disproportionate share of inbound Midwest investment by being the cheapest. (I’ll get to Pence later).

The subtle tweaks have been income redistribution from metro Indianapolis (documented by the Indiana Fiscal Policy Institute) and using the above techniques and others to apply the brakes to efforts by metro Indy to further improve its quality of life advantage over many other parts of the state (see my column in Governing magazine for more). One obvious example is a recent move by the Indiana University School of Medicine to build full four year regional medical school campuses and residency programs around the state with the explicit aim of keeping students local instead of having them come to Indianapolis for medical training.

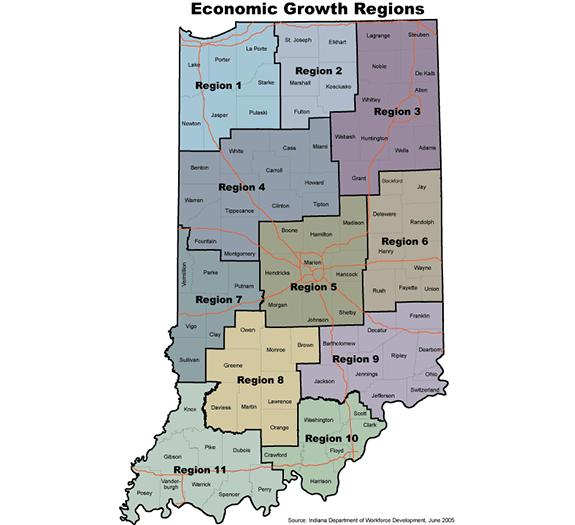

What there’s been next to nothing of is any sense of metropolitan level or even regional thinking. The state does administer programs on a regional level, but the strategy is not regionally oriented and the administrative borders don’t even line up. Here are the boundaries of the various workforce development boards:

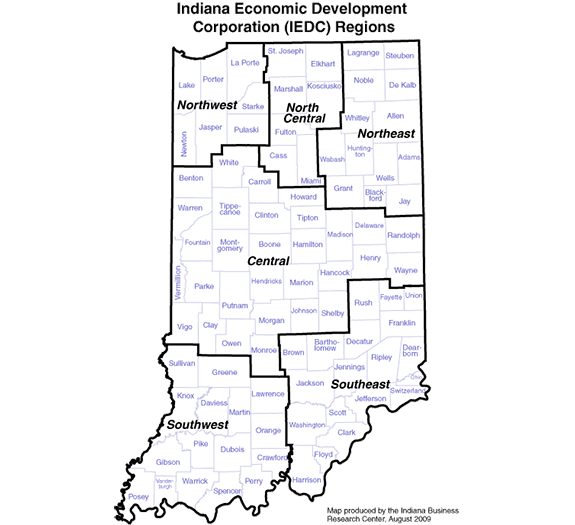

There’s a semi-metropolitan overlay, but as I’ve long noted places like Region 6 are economic decline regions, not economic growth regions. Here’s how the Indiana Economic Development Corp. sees the world:

These are not just agglomerations of the workforce districts, there are numerous differences between them. The point is that clearly the organization is driven by administrative convenience and the political need for field offices, not a metro-centric view of the world or strategy.

Add it all up and it appears that Indiana has decided to fight against all three new realities above rather than adapting to them. It rejects metro-centricity, imposes a uniform policy set, and is oriented towards trying to reflate the most struggling communities. I don’t think this was necessarily a conscious decision, but ultimately that’s what it amounts to.

When you fight the tape, you shouldn’t expect great results and clearly they haven’t been stellar. Since 2000, Indiana comfortably outperformed perennial losers Michigan and Ohio on job growth (well, less job declines), but trailed Kentucky, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri. But notably, Indiana only outpaced Illinois by a couple percentage points. That’s a state with higher income taxes (and that actually raised them) that’s nearly bankrupt and where the previous two governors ended up in prison. Yet Indiana’s job performance is very similar. What’s more, Hoosier per capita incomes have been in free fall versus the national average, likely because it has only become more attractive to low wage employers.

Fiscal discipline, low taxes, and business friendly regulations are important. But they aren’t the only pages in the book. Workforce quality counts for a lot, and this has been Indiana’s Achilles heel. (My dad, who used to run an Indiana stone quarry, had trouble finding workers with a high school diploma who could pass a drug test and would show up on time every day – hardly tough requirements one would think). Also aligning with, not against market forces is key.

I will sketch out a somewhat different approach. Firstly, regarding the chronically unemployed, clearly they cannot be written off or ignored. However, I see this as largely a federal issue. We need to come to terms with the reality that America now has a population of some million who will have extreme difficulty finding employment in the new economy (see: latest jobs report). We’ve shifted about two million into disability rolls, but clearly we’ve to date mostly been pretending that things are going to re-normalize.

For Indiana, the temptation can be to reorient the entire economy to attract ultra low-wage employers, then cut benefits so that people are forced to take the jobs. I’ve personally heard Indiana businessmen bemoaning the state’s unemployment benefits that mean workers won’t take the jobs their company has open – jobs paying $9/hr. Possibly the 250,000 or so chronically unemployed Hoosiers may be technically put back to work through such a scheme – eventually. But it would come at the cost of impoverishing the entire state. Creating a state of $9/hr jobs is not making a home for human flourishing, it’s building a plantation.

Instead of creating a subsistence economy, the focus should instead be on creating the best wage economy possible, one that offers upward mobility, for the most people possible, and using redistribution for the chronically unemployed. You may say this is welfare – and you’re right. But I would submit to you that the state is already in effect a gigantic welfare engine. In addition to direct benefits, the taxation and education systems are redistributionist, and the state’s entire economic policy, transport policy, etc. are targeted at left-behind areas (i.e., welfare). Even corrections is in a sense warehousing the mostly poor at ruinous expense. So Indiana is already a massive welfare state; we are just arguing about what the best form is. I think sending checks is much better than distorting the entire economy in order to employ a small minority at $9/hr jobs – but that’s just me. Again, we are in uncharted territory as a country and this is ultimately going to require a national response, even if it’s just swelling the disability rolls even more. I do believe people deserve the dignity of a job, but we have to deal with the unfortunate realities of our new world order.

With that in mind, the right strategy would be metro-centric, focusing on building on the competitively advantaged areas of the state – what Drew Klacik has called place-based cluster – and competitively advantaged middle class or better paying industries.

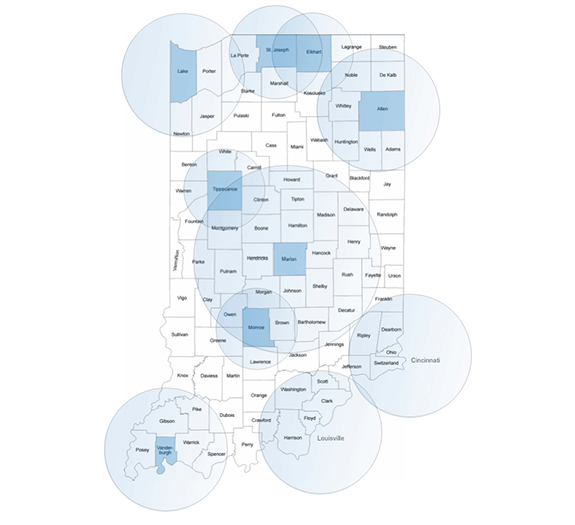

Contrary to some of the stats above, this is not purely an Indianapolis story. Indiana has a number of areas that are well-positioned to compete. Here’s a map with key metro regions highlighted:

This may look superficially like the maps above, but it is explicitly oriented around metro-centric thinking. Metro Indy has been doing reasonably well as noted. But Bloomington, Lafayette, and Columbus (sort of small satellite metros to Indy) have also done very well. In fact, all three actually outperformed Indy on STEM job growth.

Additionally, three other large, competitively advantaged metro areas take in Indiana territory: Chicago, Cincinnati, and Louisville. These are all, like Indy, places with the scale and talent concentrations to win. True, none of the Indiana counties that are part of those metros is in the favored quarter. But they still have plenty of opportunities. I’ve written about Northwest Indiana before, for example, which should do well if it gets its act together.

This covers a broad swath of the state from the Northwest to the Southeast. It comes as no surprise to me that Honda chose to locate its plant half way between Indianapolis and Cincinnati, for example.

The state should align its resources, policies, and investments to enable these metro regions to thrive. This doesn’t mean jacking up tax rates. Indiana should retain its competitively advantaged tax structure. But it should mean no further erosion in Indiana’s already parsimonious services. The state is already well-positioned fiscally, and in a situation with diminishing marginal returns to further contraction.

Next, empower localities and regions to better themselves in accordance with their own strategies. This means an end to one size fits all, least common denominator thinking. These regions need to be let out from under the thumb of the General Assembly. That means more, not less flexibility for localities. Places like Indianapolis, Bloomington, and Lafayette would dearly love to undertake further self-improvement initiatives, but the state thinks that’s a bad idea. (I believe this is part of the subtle re-balancing attempt I mentioned).

It also means using the state’s power to encourage metro and extended region thinking. For example, last year within a few months of each other the mayors of Indianapolis, Anderson, and Muncie all made overseas trade trips – separately and to different places. That’s nuts. The state should be encouraging them to do more joint development.

This also means recognizing the symbiotic relationship that exists between the core and periphery in the extended Central Indiana region, clearly the state’s most important. The outlying smaller cities, towns, and rural areas watch Indianapolis TV stations, largely cheer for its sports teams, get taken to its hospitals for trauma or specialist care, fly out of its airport, etc. Metro Indianapolis and its leadership have also basically created and funded much of the state’s economic development efforts (e.g., Biocrossroads) and many community development initiatives (the Lilly Endowment). Many statewide organizations are in effect Indianapolis ones that do double duty in serving the state. For example, the Indiana Historical Society. (There is no Indianapolis Historical Society).

On the other side of the equation, Indianapolis would not have the Colts and a lot of other things without the heft added from the outer rings out counties that are customers for these amenities. It benefits massively from that, particularly since it’s a marginal scale city. One of the biggest differences between Indy and Louisville is that Indy was fortunate enough to have a highly populated ring of counties within an hour’s drive.

So in addition to aligning economic development strategies around metros, and freeing localities to pursue differentiated strategies, the state should encourage the next ring or two of counties that are in the sphere of influence of major metros to align with their nearest larger neighbor.

Contrary to popular belief, this is a win-win. When I was in Warsaw, Indiana, people were concerned that many highly paid employees of the local orthopedics companies lived in Ft. Wayne. From a local perspective, that’s understandable and obviously they want to be competitive for that talent and should be all means go for it. On the other hand, what if Ft. Wayne wasn’t there for those people to live in? Would those orthopedics companies be able to recruit the talent they need to stay located in small town Indiana?

It’s similar for other places. Michael Hicks, and economist at Ball State in Muncie, said, “Almost all our local economic policies target business investment and masquerade as job creation efforts. We abate taxes, apply TIFs and woo businesses all over the state, but then the employees who receive middle-class wages (say $18 an hour or more) choose the nicest place to live within a 40-mile radius. So, we bring a nice factory to Muncie, and the employees all commute from Noblesville.” Maybe Muncie isn’t completely happy about this, understandably. But would they have been able to recruit those plants at all (and the associated taxes they pay and the jobs for anybody who does stay local) if higher paid workers didn’t have the option to live in suburban Noblesville? Would the labor force be there?

I saw a similar dynamic in Columbus. Younger workers recruited by Cummins Engine chose to live in Greenwood (near south suburban Indy). Columbus wants to keep upgrading itself to be more attractive – a good idea. But the ability to reverse commute from Indy is an advantage for them.

Louisville, Kentucky has one of the highest rates of exurban commuting the country because so many Hoosiers in rural communities drive in for good paying work.

This is the sort of thinking and planning that needs to be going on. Realistically, most of these small industrial cities and rural areas are not positioned to go it alone and they shouldn’t be supported by the state in attempting to do so. They need to a align with a winning team.

There are two groups of places that require special attention. One is the mid-sized metro regions of Ft. Wayne, Evansville, and South Bend-Elkhart. These places are too far from larger metros and aren’t large enough themselves to have fully competitive economies. No surprise two of the three lost STEM jobs. Evansville has done better recently on the backs of Toyota, but has a vast rural hinterland it cannot carry with its small size. The region has done ok of late, but it has also received gigantic subsidies in the form of multiple massive highway investments, and now a massive coal gasification plant subsidy. I don’t believe this is sustainable. These places need special assistance from the state to devise and implement strategies.

The other grouping consists of rural and small industrial areas that are too far outside the orbit of a major metro to effectively align with it. This would includes places like Richmond or Blackford County. They might get lucky and land a major plant, but realistically they are going to require state aid for some time to maintain critical services.

For the last two groups especially, there also needs to be a commitment by the state’s top brain hubs – Indy and the two university towns – to applying their intellectual and other resources to the difficult problem at hand. Part of that involves helping them be the best place of their genre that they can. While cities are competitively advantaged today, not everybody wants to live in one. So there is still an addressable market, if not as large, for other places.

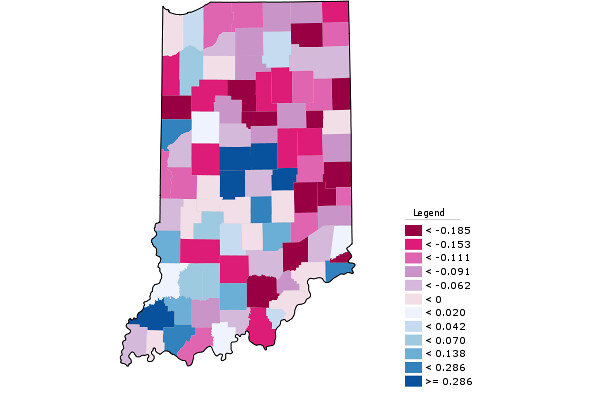

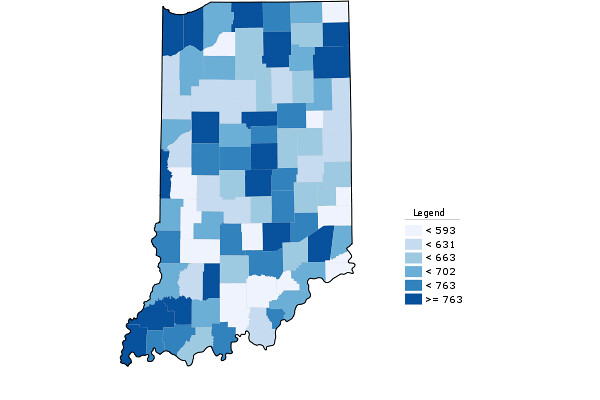

Put it together and here’s the map that needs to be changed. It’s percentage change in jobs, 2000-2012:

Pretty depressing. Urban core counties had some losses, but suburban Indy, Chicago, and Cincy did decently (Louisville’s less well), plus Bloomington area, Lafayette, and Columbus. You see also the strong performance of Southwest Indiana which is fantastic, but the sustainability of which I think is in question. Wages are higher in metro areas too, by the way. Here’s the average weekly wage in 2012, which shows most of the state’s metros doing comparatively well:

In short, I suggest:

- Retain lean fiscal structure but limit further contractions

- Goal is to build middle class or better economy, not bottom feeding

- Align economic development efforts to metro areas, particularly larger, competitively advantages locations. Align capital investment in this direction as well.

- Greater local autonomy to pursue differentiated strategies for the variegated areas of the state

- Special attention/help to strategically disadvantaged communities, but not entire state policy directed to servicing their needs.

- Utilization of transfers for the chronically unemployed pending a federal answer, but again, not redirection of state policy to attract $9/hr jobs.

This requires a lot of fleshing out to be sure, but I think is broadly the direction.

Back to Gov. Mike Pence, would he be on board with this? He’s Tea Party friendly to be sure and interested in fiscal contraction. But he’s not a one-trick pony. He’s actually taken some interesting steps in this regard. He is subsidizing non-stop flights from Indianapolis to San Francisco for the benefit of the local tech community. He also wants to establish another life sciences research institute in Indy. And he’s talked about more regionally focused economic development efforts. It’s a welcome start. I think he groks the situation more than people might credit him for. Keep in mind that he did not establish the state’s current approach, which arguably even pre-dated Mitch Daniels, and he has to deal with political realities. And if as they say only Nixon could go to China, then although a reorienting of strategy is not about writing big checks, still perhaps only someone with conservative bona fides like Pence can push the state towards a metro-centric rethink.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile, where this piece originally appeared.