The name sounds like something a screenwriter might contrive – but not even Hollywood would buy a character as unlikely as William May “Billy “Garland.

Maybe that’s why so few of us have heard of Garland despite his role as one of the self-made SoCal aristocrats of the early 20th century who helped define the LA we inhabit today.

There’s a “truth-is-stranger-than-fiction” quality to Garland’s life story – from a New Englander with ailing lungs to omnipresent power broker in the City of Angels.

Or maybe it’s an “only-in-LA” tale.

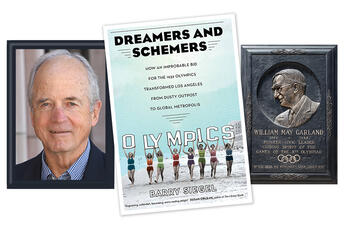

But Garland did exist, no matter how you slice it, and his tale is worth the telling it gets in a newly published non-fiction narrative from the University of California Press titled “Dreamers and Schemers – How an Improbable Bid for the 1932 Olympics Transformed Los Angeles From Dusty Outpost to Global Metropolis.”

All of this – Garland, his story, the book’s author – stretches across SoCal.

And it comes at an opportune moment, with LA just getting ready to get ready to host another Olympiad.

Start with the author, Barry Siegel, who grew up on the Westside in simpler times and went on to become a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer for the LA Times before founding and running the Literary Journalism program at the University of California-Irvine.

Siegel remains an LA guy even with his UCI credentials. He’s been known to haunt Art’s Deli on Ventura Boulevard in Studio City, and he’s just as comfortable with Factor’s Deli on Pico Boulevard in the Pico Robertson district, not far from where he grew up in the 1950s.

Those were the days when Siegel and his dad regularly made the drive down Exposition Boulevard to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, where the newly arrived Dodgers played for several years before a neighborhood in Chavez Ravine made way for the team’s own stadium just northwest of Downtown.

Siegel didn’t know then that he’d spend a good chunk of time decades later learning about how the Coliseum came to be. He couldn’t have known that he’d be professionally captivated for a spell by the driving force behind the stadium that opened with capacity for 75,000 fans and grew to accommodate 101,000 at one point.

And how would he have known?

How many of us have spent much time pondering why LA built a gigantic sports palace in 1923, when the city was still three decades away from big league sports and USC had yet to play its first game against Notre Dame?

How many of us wonder why the Coliseum went up nine years before LA put it to its intended use as host of the 1932 Olympics?

The short answer is Billy Garland.

The long answer is given ably by Siegel, who takes readers on a tour of yesteryear’s LA and manages to link the history and characters – those dreamers and schemers – to the present.

The past and the present came together for Siegel thanks indirectly – but nevertheless in large part – to the efforts of Peter Ueberroth, another fellow with ties to LA and OC.

Much of Siegel’s research came courtesy of the archives of the LA 84 Foundation, which was established with the surplus of funds generated by the 1984 Olympics that Ueberroth led in LA.

The LA 84 Foundation is located in the West Adams district in South LA – where Garland lived in one of the many mansions populated by business magnates and Hollywood stars back in the day. The foundation operates a treasure trove of a library and archive alongside programs committed to “radically expanding youth sports opportunities; and improving the social, academic and health outcomes through structured sports participation,” according to its stated mission.

Ueberroth these days runs the Contrarian Group, a venture capital and private equity firm based in Newport Beach, which gives him a perch in the world of commerce – one of a number of similarities to Garland.

Both Garland and Ueberroth led an edition of the Olympic games in Los Angeles as the global movement faced existential threats.

Garland’s 1932 games came as the world grappled in the depths of the Great Depression.

Ueberroth’s turn came amid some diplomatic dog days in 1984, when the games were stuck with some global payback for the U.S.’ move to boycott the preceding Olympiad in Moscow. The Soviet Union commanded more than a dozen satellite states at the time, and it responded with a boycott of its own, putting a crimp in the global turnout of LA’s games.

The Soviet boycott compounded a structural problem in the very concept of staging the global sports festival every four years – the LA games were preceded by a string of financial disasters for Olympic host cities that stretched back 20 years.

Garland managed to pull the games off – and he might have forever changed the equation on promoting LA in the process.

Ueberroth also pulled them off, putting on a show that defied predictions of an international cold shoulder and civic meltdown to revive the Olympic movement, setting a new standard for staging the games.

More common ground for Garland and Ueberroth: Both were self-made entrepreneurs who took on the challenges of the Olympics at the urging of a representative of LA’s institutional power structure.

Harry Chandler, boss of the LA Times and perhaps the ultimate mover and shaker in SoCal’s history, was in Garland’s corner.

Ueberroth took on the challenge at the request of Mayor Tom Bradley, who served in LA’s top elective office longer than anyone in history, bridging the city’s transition from a place where Anglo-Americans kept a tight lid on the good life to an atmosphere that continued the trail toward its remarkable diversity of today.

Both Garland and Ueberroth had to find ways to stage the games without public financing.

Garland worked around the wishes of voters who had voted down a referendum to publicly finance the construction of the Coliseum through bonds – although Siegel illuminates how Garland fixed it so they ultimately bore the risk whether they realized it or not.

Ueberroth lined up with the 80% or so of Angelenos who voted against putting any public money toward 1984 games. He then pioneered corporate sponsorships and other revenue streams that produced the surplus and changed the equation for the Olympic movement.

There also were some key differences between Garland and Ueberroth. Garland was a dreamer and a schemer. So were Chandler, E.L. Doheny and a host of other civic leaders who formed an upper crust of power brokers who took hold of LA in the first half of the 20th century and led – sometimes dragged – the city along a path of steady economic and population growth.

Ueberroth represented a different LA – a city entering a new phase of its history under the helm of a mayor who represented a break from the past.

Ueberroth brought vision and transparency – a refinement of the dreams and schemes of Garland’s age.

The similarities and differences between the two bring to mind the 2028 Olympics, which are slated for LA and raise an obvious question: Who will take the baton from Garland and Ueberroth?

Will they dream and scheme or lean toward vision and transparency?

What tangible assets might the 2028 games leave as a legacy for LA?

Difficult to say for a number of reasons.

Garland and Ueberroth might have been buffeted by events beyond their control – an economic crash and a diplomatic breakdown, respectively – but their institutional partners were steady. Chandler and Bradley provided continuity throughout the runup to the games in both instances.

Garland and Ueberroth both were the clearly designated leaders on their respective Olympian efforts.

The effort to land the 2028 Olympics came under the leadership of current Mayor Eric Garcetti, who will be long out of office by the time planning gets into full gear for those games.

Another key player in landing the 2028 games has been Casey Wasserman, scion of a Hollywood legend, well-known talent agent and studio executive Lew Wasserman.

The younger Wasserman’s professional life is steeped in sports as an agent, one-time franchise owner, and UCLA athletics booster.

Now he’s chairman of the LA 2028 Organizing Committee, putting him next in line after Ueberroth and Garland.

Ueberroth came along in a much different world – and a much different LA – from what Garland wrangled for the 1932 games.

The 2028 games that Wasserman has signed on to lead will take place in a world that’s much different from the atmosphere that surrounded Ueberroth’s games. Indeed, the digital revolution we’re living through means that Wasserman’s games will come in a world and city very much changed from today – let alone 1984 – and it seems unlikely he’ll get the benefit of the sort of continuity Garland and Ueberroth could count on in the form of Chandler and Bradley.

Siegel’s “Dreamers and Schemers” is an entertaining look at the life of a largely forgotten giant of LA’s history in Garland. The book also gives plenty of reason to realize that an Olympiad is a matter of great consequence for a host city – and now is the time to start paying attention to planning for the 2028 games.

Sullivan is founder and chief columnist of SullivanSaysSoCal.com

@SullivanSaysSC