A long succession of urban theorists, including Jane Jacobs, have intuited, implied, or proclaimed the “organic” nature of cities. This organic concept of cities describes them as self-organizing, complex systems that might appear messy, but that disorderliness belies a deep structure governed by fundamentally rule-bound processes.

Is this view of cities just another esoteric construct, or a valid theory that has yet to take root and become operational? This article examines the trajectory and recent research into the concept for revelations and implications to the field of planning.

It's organic!

In the 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs mused: “[…] why have people professionally concerned with cities not identified the kind of problem they had?” as their colleagues in the life sciences did. She was not alone to guess that city problems “[…] are all problems which involve dealing simultaneously with a sizeable number of factors which are interrelated into an organic whole.”

Fig.1 (left) A network of leaf veins, inherently organic, appears haphazard and unsystematic, yet also rule-bound (e.g., a hierarchy and fractal scaling). The leaf is observably patterned but also non-replicable and unique. (right) A network of streets, which, by appearing vein-like and messy, earned this city (Medina, Fez), among others, the classification “organic.” The first results from an enigmatic “genetic code,” the second from a traceable “generative code.” Both unfold over time—a leaf in weeks, a city in centuries.

Soon after (1965), Christopher Alexander showed that “a city is not a tree” (i.e., a simplistic geometric construct), but rather a complex Venn-type diagram, “with multiple cross links and overlapping sets that can be understood but defy a designer’s ability to conceptualize them.” Alexander then admits: "I cannot yet show you plans or sketches [of such a city]. It is not enough merely to make a demonstration of overlap – the overlap [of sets] must be the right overlap.”

The “right” overlap remains observable but, evidently, intractable and unquantifiable—a handicap for planning professionals who need actionable concepts. Similar outcomes resulted from other attempts to create “a science of cities”—brilliant insights and fierce debates, but little tangible guidance.

Biomorphic

When grasping for a concrete, tangible model biomorphism holds instant appeal. In comparing the left and right sides of Figure 1, each showing networks at vastly different scales, we see striking similarities that have led theorists to conflate the configuration of street networks with the proclaimed “organic” nature of a city. In fact, leaf vein patterns encompass numerous distinct types and several variations of each—many entirely dissimilar in configuration to that of figure 1. The same applies to village/town/city street patterns; they too vary widely. Figure 1 shows just one specimen of many. In addition to their vein pattern variety, leaves, just as cities, span a thousand-fold range in size—from pine mini-leaves to banana mega-leaves (Fig.2). This analogy dissolves into a multitude of questions about which comparisons are meaningful or fruitful.

Fig. 2 Leaves: vein patterns and leaf sizes vary as much as street patterns and size of settlements—no representative type or size exists that can claim exclusivity to the “organic” label. All of them are organic.

These descriptive facts reveal the futility of trying to fathom an obscure entity (“the organic city”) by incidentally built form shapes and by analogy to the chosen forms of living things—mixing scales and focusing on the appearance of disparate subcomponents in a conceptual mishmash. This exploratory track of biomorphism left the question of what is “organic” about a city unanswered and planners bewildered. It also led to seeking old, presumed “organic” forms as prototypes for building new ones—to no avail (as we discussed here). But the “organic” intuition persists.

A New Thread

The question that Jacobs asked, rhetorically, in 1961: “Why have cities not […] been identified, understood and treated as problems of organized complexity?” found its answer in specialized research after 1980 —the tools for such perspective and treatment were previously unavailable.

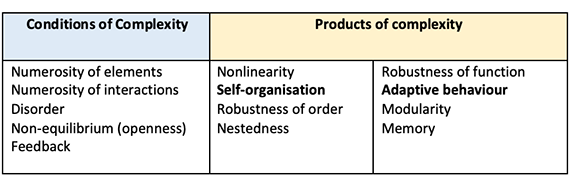

Powered by new computation and simulation tools, the science of (organized) complexity has made big strides. A first, decisive departure from previous approaches proceeds from the realization that a city is “[…] really it’s own new thing, for which we don’t have a strict analogy anywhere else in nature” (Bettencourt 2013). It is neither a “tree” nor semilattice, neither is it leaf-like nor anthill-like. It shares essential attributes with many complex systems (e.g.beehives, the brain, the Internet, the stock market, and ecosystems), but bears no resemblance to any. These attributes have now been identified and crystalized into a lens through which a new appreciation of what we observe in cities can guide future investigations (Table 1).

Table 1. Conditions and products of complexity (reconstructed from "Measuring complexity" by K. Wiesner and J. Ladyman) that produce detailed elaboration. Some terms are self-explanatory, others obscure, but terms are shown here as proof of in-depth investigation of the subject.

Research in a variety of complex systems clarifies that “[…] a complex system is a system that exhibits all of the conditions for complexity and at least one of the products emerging from the conditions.” (Link in table caption) An example of self-organization and robustness of order in cities has been hiding in plain sight.

A Curious, Surprising Variant

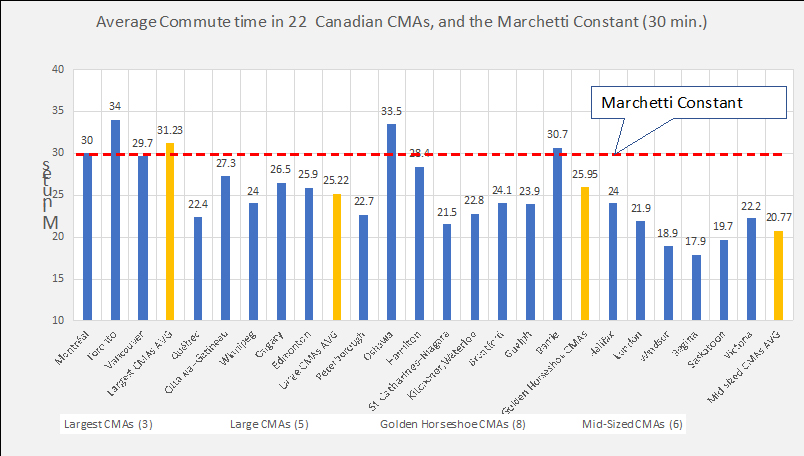

One of Jacobs’ observations already presaged the numerosity of elements and of interactions and also the outcome of robustness of order: “[…] intricate order—a manifestation of the freedom of countless numbers of people to make and carry out countless plans—Is in many ways a great wonder.” Recently, planners were struck by an inescapable contradiction between continual city growth (in some cases by orders of magnitude) and the constancy of the daily commute time, coined “the Marchetti Constant” (1994). Laube, Kenworthy and Zeibots (1999) found that the average commute time for 46 international cities is 28.9 minutes, ranging from 25.3 to 34.0 min. They cite an earlier study that shows journey-to-work times in the UK holding constant at around 30 minutes over the past 600 years. To these examples, we add the 2016 stats for Canadian cities. (Fig 3)

Fig. 3 Average commute time in 22 Canadian CMAs and the averages (yellow bars) of groupings of CMAs- source:(StatsCan 2016)

As in the previous examples, these cities vary greatly in age, land area, population, and density, as they do in wealth, car ownership rates, provision and quality of transit, road capacity, and climatic conditions. Yet, in spite of these differences, they register consistent commute times. This counterintuitive finding is surprising, but only when the city is seen from a mechanistic perspective of causes and effects (i.e., larger size = longer commute time). Through this approach, the apparent disparity between city expansion and constancy of commute time would elude analysis due to the multiplicity of variables and because it misses a confounder: “adaptive behavior.” But from the complex systems viewpoint, this result can be seen as an expected outcome, “robustness of order,” or a Jacobsian “intricate order”.

Solution, Evidence, Action

In a complex system that produces opportunity, wealth, health, safety, and security for its members, such as a city, time is a resource. By implication, unproductive time is a liability or a fault. A system might be expected to react in ways that reduce this liability. And since a multitude (or “numerosity”) of independent agents and an even greater number of potential interactions between them affect this outcome, it would be far too complex a problem to solve, if at all possible, with top-down interventions. Here, then, we have strong evidence of a bottom-up self-organization achieved through adaptive behavior by numerous agents “making countless plans.” These two traits are expected products of a complex system (i.e., “organic wholes”). (Fig. 4)

Fig.4 The “organic” emoji: The most succinct embodiment of the “organic” nature of cities, is a vast, empty, lifeless square at daytime, which later in the day mutates into an exuberant, energetic place of exchange by a multiplicity of individuals each pursuing their own goals. Many English towns were born of and at the places of open fairs and markets. (Mark Girouard)

If at least one constant has been found, other metrics might also exist that indicate an optimal, “healthy” system, analogous to metrics found in diagnostic tools for living organisms (e.g., Body Mass Index, blood pressure, reflexes, etc.). Identifying such metrics can enhance the understanding of “the-city-as-a-complex-system” concept. It is meaningless and unhelpful to appraise a city’s performance without a reference to a baseline stemming from the city itself.

More unhelpful is the tendency to revert back to the mechanistic model and interpret this newfound constant as proof for reverse cause-and-effect intervention, as in: If commute time is a universal constant, then building more roads (to reduce travel time) is unwarranted. It is hard to imagine that the Romans would have made this argument two millennia ago, or that railroads would have stopped expanding in the 19th century on these grounds: Extensive transport networks are integral to and vital for empires (i.e., complex economic and political systems) or any multi-city or -country unions. The pragmatic question here is not whether more transport infrastructure is needed but rather what the balance point is (i.e., a metric) between demand for total network capacity (for all modes) and available supply per inhabitant to render the entire system optimal and productive.

Pause and Reflection

Intuitions about a city’s organic nature and biomorphism left planners without a clear conception of “the city” or the role of planning in a city's evolution. The dominant city image has been that of an artifact that can be molded at will with good intentions. Jacobs already showed how good planning intentions can misfire because of misconceptions of what constitutes “order.” The knowledge and precise description of a city as self-organizing, complex system might change all that. We now have evidence that this order comes from within and cannot be imposed. The task facing planners is to understand and unveil its organic structure with precise metrics and, along the way, define their own exact role in a multi-agent system that shapes its own function.

All photos courtesy of the author. Lead image via Flickr under CC 2.0 License

Fanis Grammenos is the director Urban Pattern Associates in Ottawa, Ontario and the author of Remaking the City Street Grid: A Model for Urban and Suburban Development. (i.e. The fused grid.) Reach him by email with questions or comments.