On the 14th October 2023, Australians were asked to vote in a national (and compulsory) referendum to alter the Constitution “to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.”

This vote – a simple “yes or “no” - was for more than just recognising indigenous Australians in the constitution: it proposed that this voice be a formal body which “may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.”

It was largely on this latter point that a vigorous and contentious debate raged. Would this create a separate class of Australian? Who would be appointed to this body? How would it work? What about the many billions of dollars already spent on indigenous issues apparently with little result – indigenous communities continue to suffer unacceptable levels of poor health, education, physical and mental abuse amongst adults and on children.

The “no” case was led by prominent indigenous Australians - Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Warren Mundine. Yes, that’s correct – not all indigenous Australians supported the proposed change and the public face of the “no” case was led by two indigenous Australians. So effective was Jacinta Nampijinpa Price that some are now suggesting she is future Prime Minister material. Should that ever happen she would make history as our first indigenous Prime Minister. (Australia currently has 11 of its national politicians proudly declaring their indigenous heritage – all of whom are freely elected. The current Federal Indigenous Affairs Minister is herself an indigenous Australian. We have already had a woman as Prime Minister – Julia Gillard, 2010-2013).

The proposal to change to Constitution was a 2022 election commitment of the Federal Labor Government, led by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. With Labor actively supporting the proposition, conservatives opposed it. The debate got political and like so many debates, truth was an early casualty and independent, unbiased information was hard to find.

Also supporting the “yes” case was a remarkable juggernaut of organisations, corporations and prominent individuals. The national airline Qantas painted jets with the “Yes” logo. Many national sporting organisations adopted a public stance in support of the “yes” campaign. Large corporates supported the “yes” campaign. One national supermarket chain promoted “yes” campaign material in its stores. Academics and Universities joined the “yes” case and many media identities and entertainment celebrities lent their support also. It would be hard to imagine a more concerted chorus of voices pleading for the nation to vote yes – to the extent that many ‘no’ campaigns failed to garner volunteer support to distribute campaign material or attend polling places. It looked overwhelming.

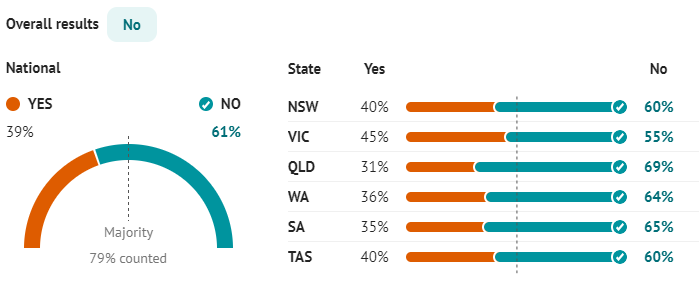

So, you can imagine the surprise when the “yes” case failed to win majority support. And it failed momentously. Constitutional change in Australia requires a majority of voters and a majority of states to effect change. It isn’t easy but the national 61% “no” vote was an emphatic rejection of the proposal. No state and only very few electorates returned a majority “yes” vote. (The exception being Canberra, the national capital which is our equivalent of Washington DC). Even regions with high proportions of indigenous Australians failed to return “yes” majorities.

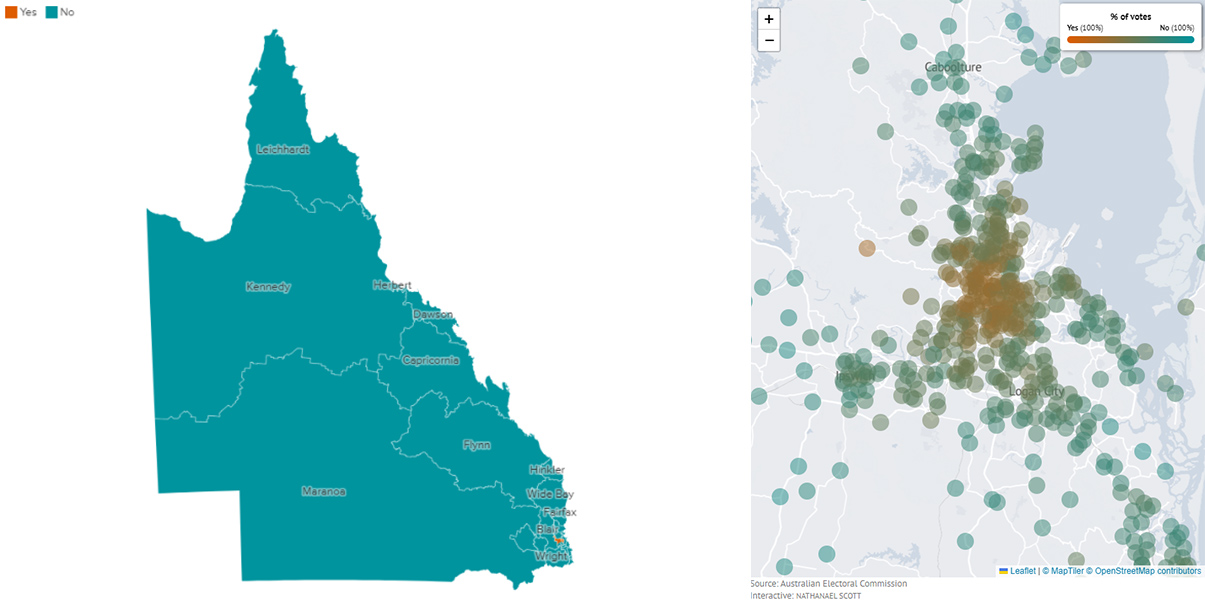

But one pattern did become quickly evident: support for the “yes” case was almost entirely concentrated within a few miles of the city cores of our capital cities. In almost algorithmic patterns, the further from a capital city centre, the lower the “yes” vote and the higher the “no.” Suburbs of capital cities, regional cities and rural areas across the country all returned strong “no” votes. This was typically the inverse of what Australians living within easy reach of capital city centres voted for.

Why?

One prominent progressive TV commentator suggested it reflected higher education qualifications of inner-city residents. The assumption that this meant he saw people without higher education degrees as of inferior intelligence was quickly howled down. After all, there are many people with doctorates who we might struggle to describe as intelligent?

True, the inner-city areas of the capitals are typically home to more higher education degrees than elsewhere. There are also typically more professional workers, on higher incomes and living in some of the most expensive real estate in the country. This concentration of wealth and privilege is, by the results of this referendum, increasingly detached from the values or beliefs of suburban and regional areas. It is also increasingly concentrated to within just a few miles of major city centres, no more. Once called “the goat cheese curtain” it is now being called “the Tesla curtain.” A significant number of inner-city Australians now have a lived experience which is unrecognisable from that of their fellow Australians.

Irrespective of opinions on whether the referendum vote could have gone another way had it restricted itself to a more benign but more broadly acceptable proposal for constitutional recognition of indigenous Australians, the geography of the voting patterns illustrates a very clear divide, which in turn creates problems for political parties. For example, the Labor Party’s traditional support base of working-class Australians has been in the suburbs and in many regions – all of which unequivocally rejected the Labor sponsored referendum question. The conservatives who supported the “no” case may look as if they have won the suburbs and regions but they have arguably also lost their traditional higher income, higher educated cohort which now inhabits inner cities.

Where does this leave traditional party-political pitches? Labor was once for the worker and for socially funded safety nets; conservatives were for business, individual responsibility, and free enterprise. Neither pitch was based on geography. Both pitches are more or less now redundant: corporates and the wealthy are now more likely to support progressive causes promoted by the left, while many workers in traditional working-class areas reject progressive causes and support conservative values around family, crime prevention, schooling, and household budget priorities.

Is it possible that existing political parties will begin to realign? This may already be underway: in the last national election in Australia, a number of traditionally “safe” conservative seats in inner urban areas fell to “Teals” who were typically wealthy but promoting very progressive agendas – some of them former conservatives themselves. The same has happened for Labor, with a number of once safe inner working-class seats now in the hands of the left leaning Greens. The political futures of major parties do not any longer lie in continuing with the traditional appeals but instead, potentially lie in a more place-based policy pitch.

In this new contest, the battle lines will no longer be based on political philosophy but on geography.

State by state

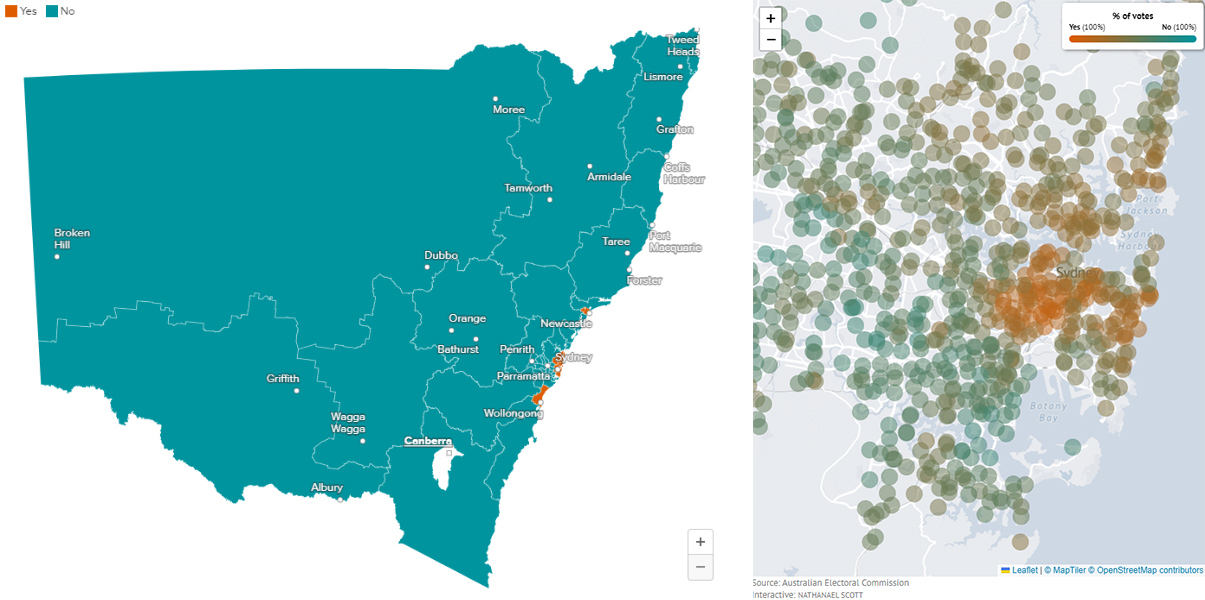

Below is the state of New South Wales (left) with “Yes” voting electorates in Sydney in orange. At right is a zoomed in map of Sydney, showing the higher proportion of “yes” polling places clustered in and around the city core. Orange represents “yes” and green represents “no.”

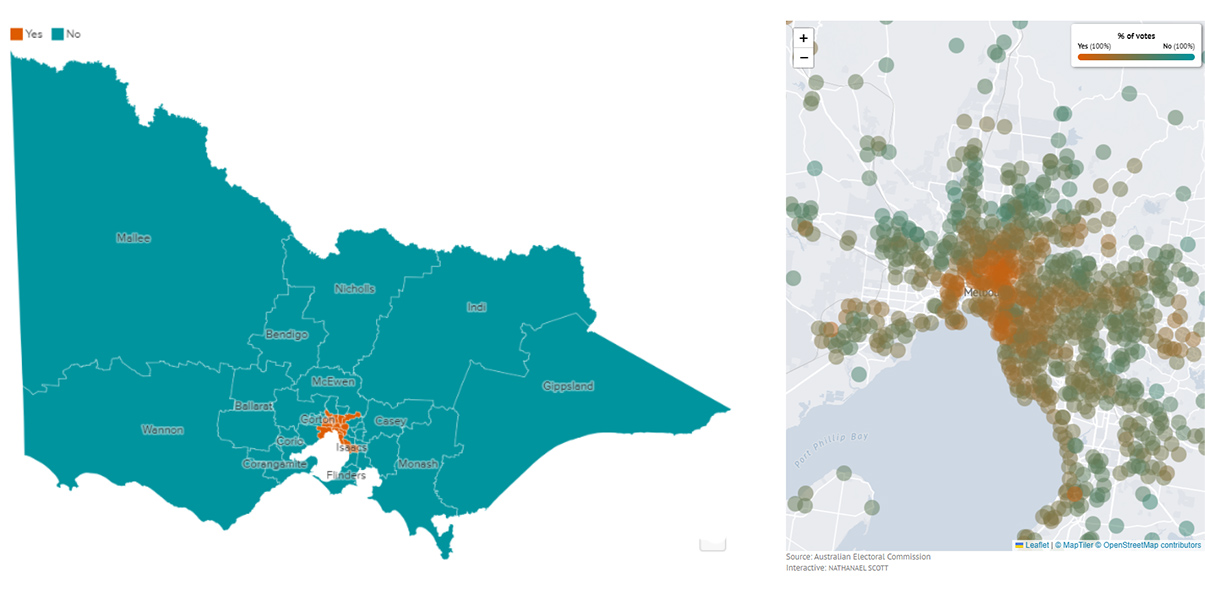

Below is the State of Victoria, showing a cluster of “yes” voting electorates in inner Melbourne, while at right the clustering of “yes” polling places around inner Melbourne is evident.

Below is a map of Queensland, with the small dot that is inner Brisbane “yes” shown in orange, while at right, the inner-city cluster of “yes” polling places is evident.

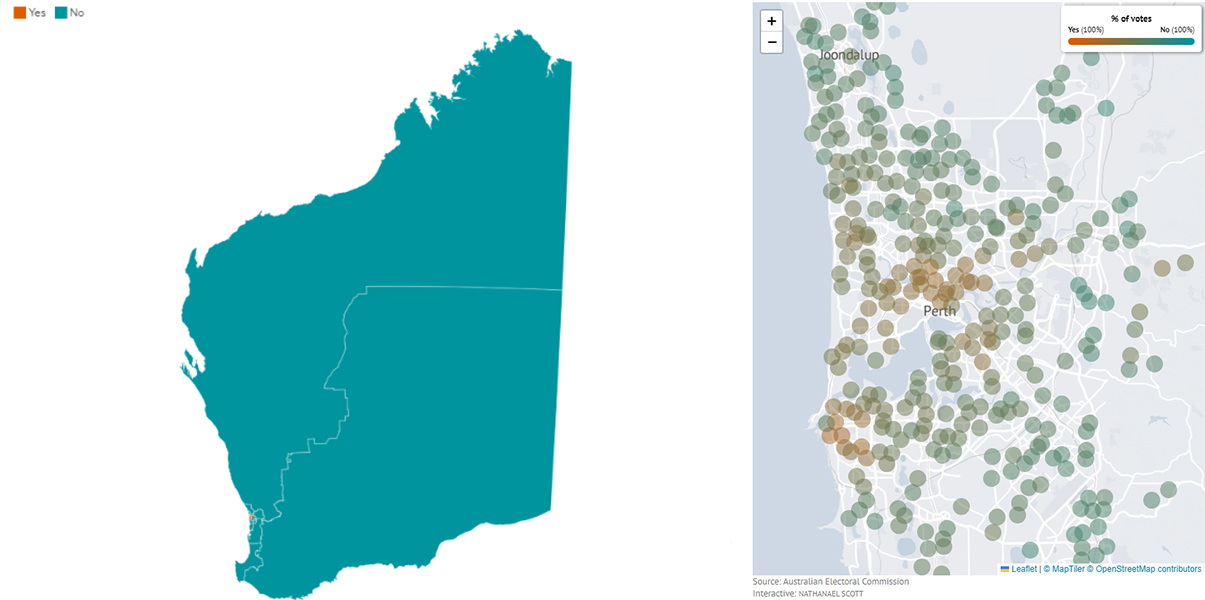

Below is West Australia, with just one electorate (barely visible) supporting the “yes” case, with the Perth metro area at right showing the pattern of support at polling places.

Ross Elliott is a leading industry practitioner with over 35 years' experience in property and urban development across a number of industry sectors. He has held senior roles with the Property Council of Australia as Executive Director, National Chief Operating Officer, and National Executive Director of the Residential Development Council. Ross has been a frequent writer and guest speaker on urban development themes both in Australia and the US. In 2018 he published a piece on Australia in a global study of suburban development by the MIT Center for Advanced Urbanism (Cambridge, Mass.) Ross is also founding director of suburban issues think tank Suburban Futures.

Photo: Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and Warren Mundine at a political rally.