The idea of “intersectionality” originated with black feminism. Black feminist activists noted that they experienced racism on account of being black and sexism on account of being women. But their experience wasn’t simply racism + sexism, but was its own unique thing as well.

One does not have to agree with the way the idea of intersectionality is applied today to recognize that there’s something valid about this basic observation. Black feminists were both out of place among white feminists and out of place among the black power activists, a male dominated milieu.

This same idea applies in many other contexts. Consider, for example, working class men. They suffer from the general challenges facing men in our society today, but also from the challenges facing the working class. As with black feminists, their experience is not simply working class + men, but has unique aspects as well.

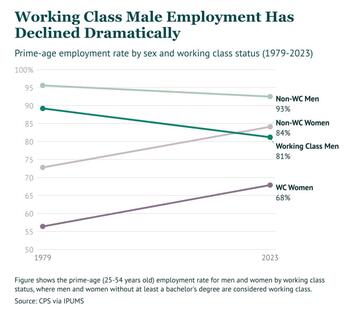

Richard Reeves’ American Institute for Boys and Men recently released a study looking at the state of working class men.* It’s a brief eleven-page paper, but with many sobering graphs.

For example, there’s been a significant decline in the share of working class men who are actually working. In fact, non-working class women are now more likely to be employed than working class men are.

This chart (above) on employment by race and class is revealing of the scale of the challenges. Although there’s a large white-gap black in most statistics generally, here we see that non-working class black men are significantly more likely to be employed than working class white men.

Read the rest of this piece at Aaron Renn Substack.

Aaron M. Renn is an opinion-leading urban analyst, consultant, speaker and writer on a mission to help America's cities and people thrive and find real success in the 21st century. He focuses on urban, economic development and infrastructure policy in the greater American Midwest. He also regularly contributes to and is cited by national and global media outlets, and his work has appeared in many publications, including the The Guardian, The New York Times and The Washington Post.

Photo: chart courtesy author.