There was a time when downtown Los Angeles was the commercial center of Southern California. According to Robert Fogelson, writing in his classic Downtown: Its Rise and Fall (1880-1950)"nearly half" of Los Angeles residents went downtown every day in the middle 1920s. A time traveler from 1925 might think that to still be the case, with the concentration of tall buildings, and the frequent press reports about downtown’s resurgence.

Downtown LA got a late start with high-rises. Until the middle 1960s, there were few buildings exceeding the 13 story height limit repealed in 1958 by city of Los Angeles. The most important exception is City Hall, opened in 1928, which is 454 feet tall (137 meters). By 1989, the city's tallest building, Library Tower (First Interstate Tower), had been opened, topping out at 1,018 feet (310 meters). The under-construction Wilshire-Grand Tower will soon rise 80 feet (25 meters) above Library Tower. From the flight path to Los Angeles International Airport (above) and many ground vistas, the vertical profile of downtown Los Angeles will continue to stand tall over the city.

Yet, far less understood is that downtown has declined in metropolitan importance for decades. Now, downtown has only 2.4 percent of employment the metropolitan area (Los Angeles and Orange Counties). Between the 2000 Census and the 2006-2010 American Community Survey, employment in the central business district dropped approximately five percent. At least four other employment areas, all freeway oriented with lower employment density, equal or exceed downtown's employment (these include the Airport-El Segundo area and nameless employment areas straddling the Santa Ana Freeway in Los Angeles County, the Harbor and San Diego Freeways in the South Bay and the Costa Mesa Freeway in Orange County). More important still, approximately two-thirds the metropolitan area's employment is not in a large employment area at all. This dispersion of employment is one reason why Los Angeles –despite its reputation for horrendous traffic – has the shortest one-way commute time of any world megacity for which there is data.

Shifting Downtown

Following World War II, the heart of downtown Los Angeles shifted west from Broadway, Hill and Spring Streets, leaving a large stock of quality commercial buildings vacant. This was well before the end of their useful lives, yet decades of disuse followed. Most of these buildings rose to the 13 floors height limit, though one, the 18 story United California Bank headquarters at 6th and Spring, was completed not long before its competitors hired moving vans to move west. Soon after, the United California Bank built the UCB Tower (now Aon Tower) on Hope Street, with 62 floors (1973), which at the time was the tallest building in the world outside New York and Chicago.

Adaptive Reuse

The UCB Building and many more on the now more residential east side of downtown been converted to apartments and condominiums under the city's creative "adaptive reuse" ordinance, which facilitates conversions from office to residential use. According to the city of Los Angeles, the ordinance has facilitated conversion of downtown commercial space into more than 3,000 residential units. Another 7,000 are either under construction or being considered.

The conversion of office buildings to residential has spread to post war structures, such as the Mobil Oil Building (now the Pegasus Apartments). This building, on Flower Street, was one of the earliest examples of the more modern styles that were to proliferate throughout the downtown areas of the nation. The Signal Oil Building, also one of the first to exceed the 13 story limit has also become residential (1010 Wilshire). This building had been the subject of an unusual 1980s remodeling that enlarged the footprint and the floors, while materially changing the outside angles and the decor. Another nearby office building (1100 Wilshire) sat empty for two decades after construction, before being converted to residential use.

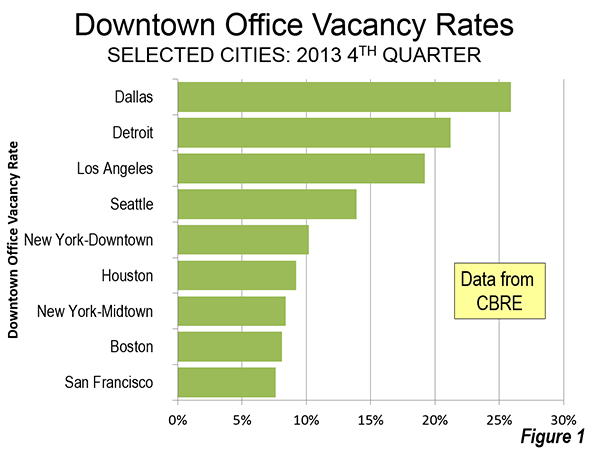

The shift to residential makes sense given that most downtown office buildings are having difficulty filling their space. Downtown's glutted office market is indicated by a 19.2 percent vacancy rate in the fourth quarter of 2013. This is better than such market laggards as downtown Detroit or downtown Dallas, both over 20 percent, but higher than the Los Angeles suburban office vacancy rate, at 15.9 percent. Downtown’s vacancy rate is also approximately double or more those of dynamic downtowns such as San Francisco, Boston, New York, and Houston, which are all under 10 percent (Figure 1).

It appears likely that the Crocker Citizens Plaza, opened as the city's tallest building in 1969 (42 floors), is slated for conversion to residential. After Crocker Bank moved to its new Crocker Center (now Wells Fargo Center) on Bunker Hill, Crocker Citizens Plaza became the AT&T Building. AT&T vacated the building and moved to the earlier 1960s Transamerica Building, which urban legend indicates was built well south of downtown because consultants convinced the developers that this would be the center of an even larger downtown. The Transamerica, now AT&T, is even more divorced from the commercial core than when it was built. By the time Crocker Citizens Plaza (now "611 Place") is converted to residential, it could be the third tallest mixed use building in downtown.

The second tallest mixed use tower could well be the prestigious Library Tower, which stands half-empty. There are rumors that the new owners may convert a large part of the structure to condominiums and a hotel. No major office skyscraper has opened in downtown Los Angeles in the last 20 years. Nor will that change when the Wilshire Grand Tower is completed. Wilshire-Grand will only be partially an office tower and will include a hotel. Only 30 of the 73 floors will be offices. This is a climb-down from the original design, which included two buildings – a 60 story office tower and a 40 floor hotel and condominium project. The new building is little of an endorsement of downtown's office demand.

Transitioning from Adaptive Reuse?

This conversions may be the tail end of trend. DT News reports that it has become more economical for many developers to construct new residential buildings, rather than to convert empty commercial buildings. As demand has increased, so have prices of existing buildings, which makes adaptive reuse less attractive. Further, many of the structures on Broadway, which casual observation might indicate have potential for conversion, but the density of development may make offering enough natural light difficult for residences.

Ups and Downs of Downtowns

As employment has dispersed throughout the Los Angeles area, there has been less of a need for a central business district. Among the nation's larger downtowns, only downtown Los Angeles has undertaken wholesale abandonment of its commercial core and built a new one. Perhaps this is, in part, because the 13-story height limit rendered the older buildings uneconomic for the second half of the 20th century.

New York (Manhattan), south of 59th Street also has seen its ups and downs. But New York did not abandon large swaths of development, only to move elsewhere. Downtown Chicago expanded northward along Michigan Avenue, but little if any of the Loop was ever abandoned and it has undergone continuous renewal. The West Coast's premium downtown areas, San Francisco and Seattle, have interspersed new development along with the old, and remain more important to their metropolitan areas than downtown Los Angeles, accounting for from four to six times its employment share (though still less than 15 percent). Even Houston, which most resembles Los Angeles in its post war downtown rebuild, managed its transformation without abandoning the historic core. And, at the same time, all are enjoying increasing residential demand, like downtown Los Angeles.

Rising Demand

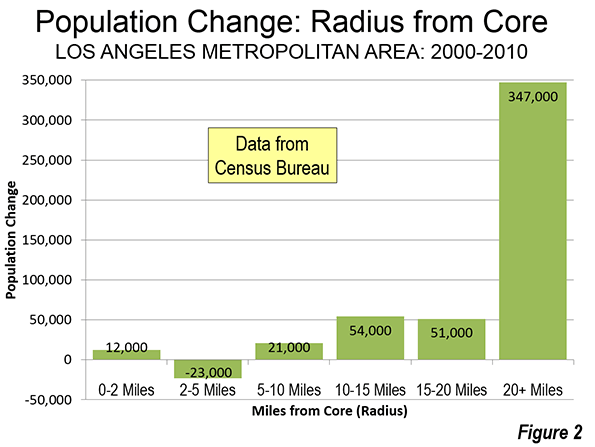

Downtown interests are rightly proud of the rising residential population. This has occurred in many downtowns across the nation. Between 2000 and 2010, areas within 2 miles of City Hall gained 206,000 residents in the major metropolitan areas (over 1 million population). However, within in the next ring, from 2 to 5 miles from City Hall the decline in population more than compensated for the core gains (minus 272,000).

The situation was the same in Los Angeles, where the Census Bureau reports that population within 2 miles of City Hall rose 12,000, while it declined 23,000 between 2 and 5 miles. The growth of downtown Los Angeles is impressive in part because it was stagnant for so many decades. In context, however, it is no "game-changer." Overall in the last decade all growth in the Los Angeles metropolitan area was outside the 5 mile ring, and 75 percent of that was more than 20 miles from City Hall (Figure 2).

A New Species is Born

It would be a mistake to characterize the emerging downtown Los Angeles as reasserting any economic primacy. Its former function is beyond revival. This was indicated by UCLA Anderson Forecast economist David Shulman, who indicated that he was "not bullish on Downtown Los Angeles." The report by public radio station KPCC continued:

"That view runs counter to the impression that downtown L.A. is staging an urban comeback. But the resurgence is more about sports and entertainment venues, restaurants and bars, loft conversions, and hotels than it is about companies that need a lot of floors in tall buildings. Nightlife and streetscapes trump florescent light and cubicles."

This refers to the new entertainment venues, such as the Staples Center, the Walt Disney Concert Hall and "LA Live," which may be joined by a new football stadium for a proposed National Football League franchise.

The transformation of downtown Los Angeles is not so much a renaissance of a business core, but a shift into a new, and different, function. The new downtown serves a function similar to that of Wilshire Boulevard’s more heavily residential high-rise district. But it's not likely to ever resemble the Upper East Side or Upper West Side in New York, not only because its residential base will remain small, but because downtown is hardly an ascendant business center. Downtown’s recovery as a residential district – with a population roughly equivalent to the suburb of Diamond Bar – is indeed impressive, but its role as a vital urban economic center remains relatively small.

-------

Photo: Downtown Los Angeles toward the Hollywood Hills and the San Fernando Valley (by author)

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

True, but - so what?

I don't think any serious person would contend that LA isn't polycentric. Polycentricity is good, but it doesn't mean low density - to the contrary, one would envisage several pockets of medium density. Places like Palms would be the model, not Manhattan. Short of building a bunch more freeways (at grade: politically infeasible; tunneled: prohibitively expensive), that would suggest that light rail is actually a sensible alternative in a lot of areas.

Similarly, I don't think the population growth data really says much except that it's easier to build in the Inland Empire and than in more central places. Market prices for rent, etc., suggests that people want to live in more central areas, That suggests the problem is insufficient building (e.g., due to restrictive zoning laws) rather than any lack of desire to live there.