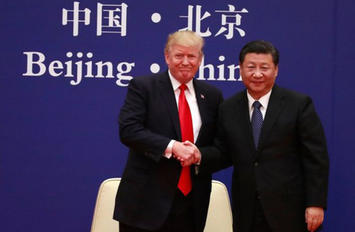

As President Trump visits China, the contrast between the president — at war with the national media, the corporate establishment, almost all of academia and even his own party — and the sure-handed Xi Jinping seems almost unbearable. Xi has consolidated power to an extent not seen since Mao’s time, while directing a global expansion of Chinese power, notably in central and south Asia as well as Africa.

Xi’s power is all the greater for how subtly it is applied. There are no great propaganda posters on the streets of Beijing. Last week at Peking University’s “Global Forum,” few scholars openly challenged the country’s authoritarian system although limited open debate and discussion was permitted. China may be authoritarian, but not crudely oppressive like the former Soviet Union, North Korea or Cuba.

What China craves, not surprisingly given its turbulent 20th century, is “order,” both at home and in its expanding roster of vassal states. Their soft authoritarianism, at least if you are not an open dissident, is now promoted as the new global “role model” in the Chinese media. No matter how much Trump tries to talk tough about no longer being a “chump,” it’s likely he will be portrayed here and abroad as ceding the center of the world stage to Xi.

The New Role Model?

China’s ascendency appeals to many in America’s intellectual classes, and not only them, who historically have a soft spot for “enlightened” autocrats and overweening bureaucracies. In the progressive era, the lodestone was imperial Germany, in the 1930s for many the “future” was to be seen in the Soviet Union and even fascist Italy. In the 1980s, Japan emerged as the role model, followed in the late 1990s by a united Europe that seemed to many more humane and successful than the U.S.

In all cases, these role models ultimately failed to stay competitive with the United States. The Soviet Union is long gone and Mussolini, at best, is regarded as an almost comically bombastic figure. Both Japan and Europe have lagged the United States in innovation and are fading demographically.

To be sure, China may pose a greater challenge than any other in our history. It is poised to surpass the U.S. in terms of aggregate economic output; it enjoys a rapidly growing educated population, bustling cities and a strong sense of national unity. It also has seen more people lifted more quickly out of poverty than any regime in history and some suggest it is about to be the leader in technology as well.

Read the entire piece at The Orange County Register.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book is The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo: Via BBC.

Ineffective?

If by "second-rate autocrat" Kotkin means an executive who refuses to use his power to the utmost to quash all dissent and punish his political enemies, then yeah, Trump is surely second-rate. It would be nice if Kotkin and other generally sound writers could manage somehow to decouple their visceral, aesthetic loathing of Trump (which is perfectly legitimate) from their assessments of his Presidency.

But Kotkin's assertion of the "ineffective politics" in the US as not constituting our historical "edge" is patently wrong. It is China, and not the US, who has made politics ineffective. It is the very efficacy of our contentious, messy politics that secures the "internal regime change" that Kotkin lauds. It is precisely the goal of the progressives, as Kotkin suggests by his historical overview, to limit the efficacy of politics.