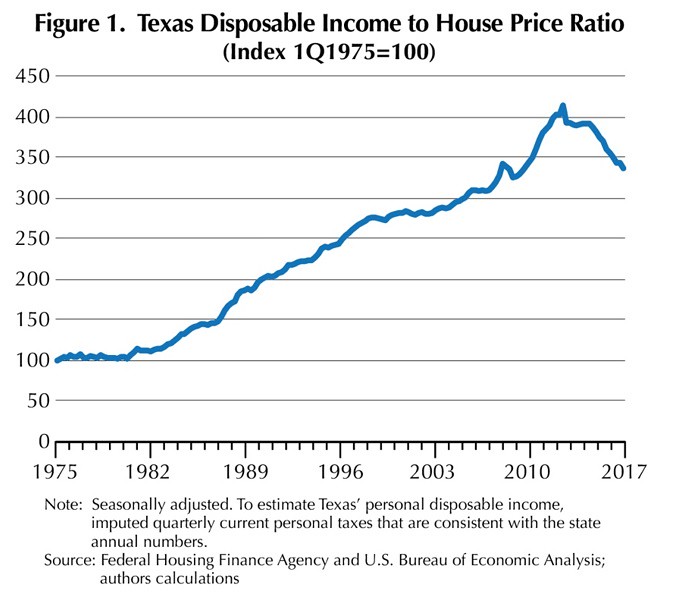

The strong recovery from the Great Recession, fueled by the shale oil boom, propelled the demand for single-family homes in Texas. Homebuilders have been unable to keep pace with increasing demand. Supply is limited by the availability of land and labor constraints, pushing up home prices. Since 2012, Texas housing prices have been rising faster than incomes (Figure 1).

Prices Rise to New Highs

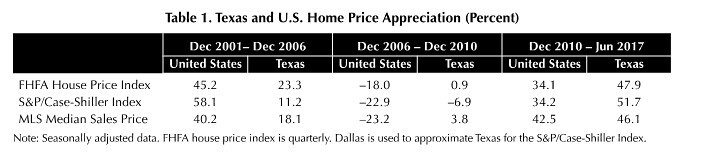

Texas has a vast supply of land suitable for development and relatively few building regulations. Construction typically responds quickly to demand, resulting in smaller home price swings than other large states. During the U.S. housing boom in the mid-2000s, Texas recorded modest home price appreciation, while prices nationwide climbed to record levels (Table 1). Similarly, when the housing market peaked and home values collapsed across the U.S., price declines in Texas were muted.

During the housing recovery, Texas price gains uncharacteristically outpaced those at the national level from December 2010 to June 2017, pushing home prices to record highs. Prices rose 43.8 percent in second quarter 2017 from fourth quarter 2007—the high before the housing bust, according to Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) data. In contrast, U.S. home prices did not surpass their prerecession peak, registered in first quarter 2007, until first quarter 2016 and were only 9.3 percent above their previous high.

Driven by Population and Economic Growth

Texas has been a leading state for domestic migration since the mid-2000s, only losing the top spot to Florida in 2015 (Figure 2). California is by far the leading “sending” state as both companies and people have increasingly departed for Texas. This influx of people isn’t limited to domestic transfers; Texas has been consistently among the top five states for international migration.

This mass migration to Texas has propelled strong population growth. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, since 1990, the state’s population has grown on average almost a full percentage point faster than the U.S. Texas’ relatively low cost of living, strong economic growth due to the most recent oil boom, and lightly regulated commercial environment have attracted businesses and people. Naturally, this has increased demand for housing, particularly in the major metros. The number of households in Texas grew 1.6 percent on average annually from 2006 through 2016, compared to 0.6 percent in the U.S. and 0.6 percent in California. The number of housing units (including apartments) also increased 1.6 percent, dragging existing-home inventories to record lows.

The strong recovery from the Great Recession catapulted the Texas economy to breakneck job growth from 2012 through 2014. Demand for housing increased as home sales began climbing in mid-2010. Employment continued to grow despite the oil bust at the end of 2014 but briefly below the national pace. After fourth quarter 2016, Texas job growth once again surpassed the U.S., fueled by the recovery in the oil sector and continued U.S. economic growth. This put pressure on housing supply.

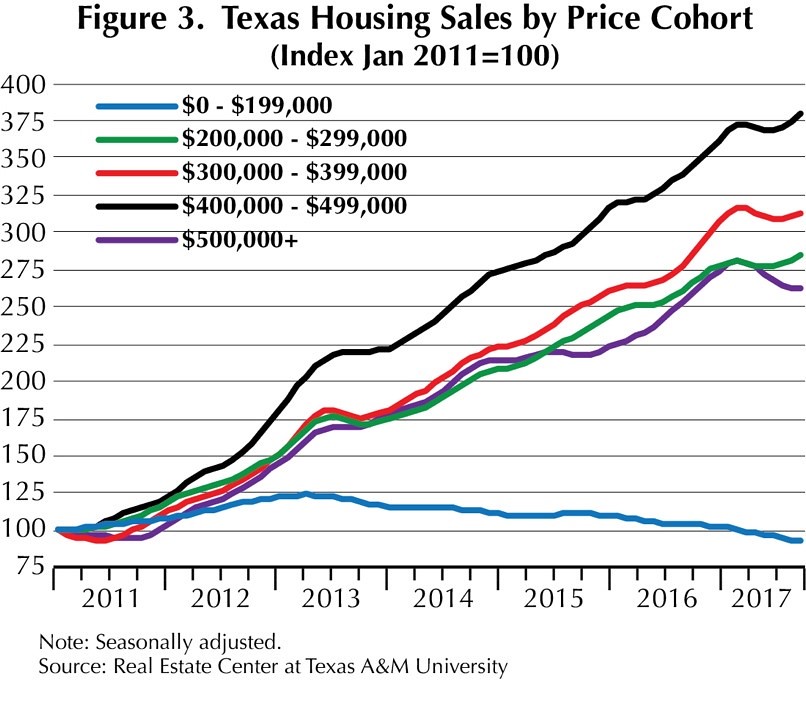

This picture is even more pronounced when home sales are divided into price ranges. Since 2011, growth in sales of homes priced between $200,000 and $499,999 have jumped in Texas (Figure 3). Sales of lower-priced homes have been constrained by the tightening supply.

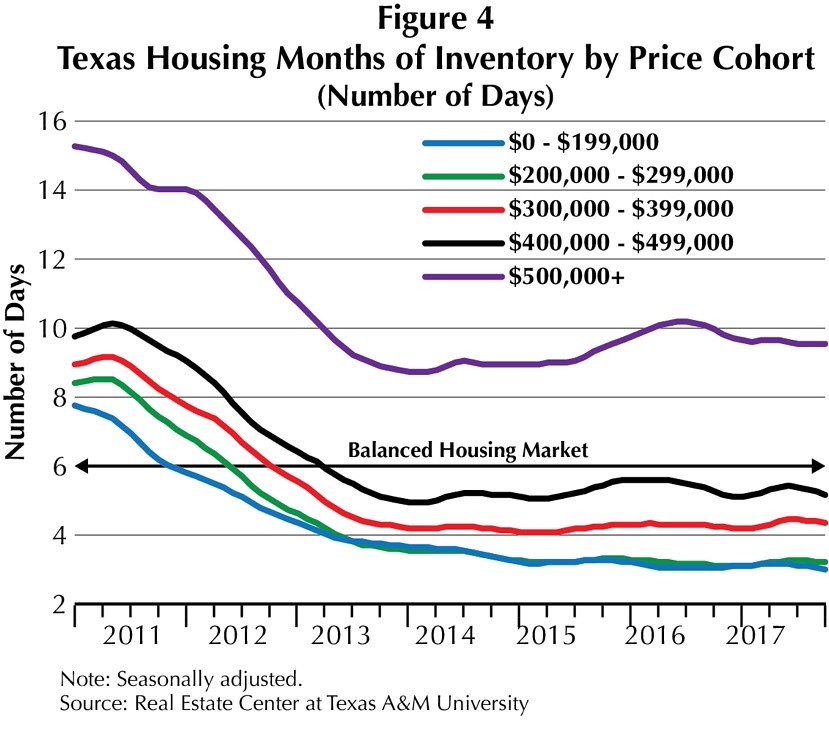

In January 2011, homes under $200,000 represented 67 percent of total sales that go through the Multiple Listing Service (MLS) compared with 41 percent in June 2017. Inventory for these entry-level homes has fallen to historically low levels of about three months (Figure 4). Around 6.0 months of inventory is considered balanced. Inventories are even tighter at the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) level, coming in at around two months for Houston and San Antonio and about one month in Austin and Dallas-Fort Worth (DFW).

Because of tight inventories, home sales in Texas’ major metros have been flat or declining in the under-$200,000 price range while growing rapidly at higher price points. This trend is most evident in Austin, which has experienced a noticeable drop in sales of homes priced below $200,000 since 2011. DFW and Houston have reported similar trends. San Antonio has fared better.

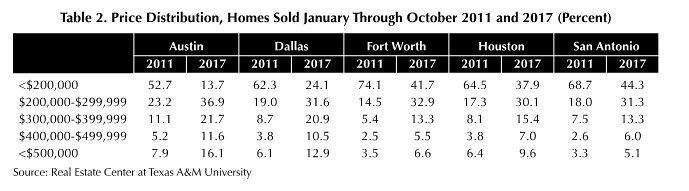

Declining Housing Affordability

With more inventory at the higher price points, sales growth at the higher end of the market has taken off. This has shifted the composition of homes sold. In 2011, 68 percent of homes sold in Texas were under $200,000. By 2017, they represented only 41 percent of the market. Table 2 compares the percentages of homes sold in each price range in the major metros for the same periods in 2011 and 2017. The lowest price range experienced largest shift is in, falling by 24 to 39 percentage points. Noticeable increases are seen in both the $200,000–$299,000 and $300,000–$399,000 price ranges. Houston and Fort Worth have similar distributions, while Austin and Dallas are skewed higher and San Antonio lower.

Supply Constraint, Accelerated Price Growth

This low-inventory, high-demand market has contributed to median home prices rising faster than incomes. This is a break with the past as income growth would exceed housing price growth. From 2012 through 2016, Texas household incomes rose at an average annual rate of 2.8 percent, while the median sales price of existing homes increased by more than twice that—7.4 percent per year on average.

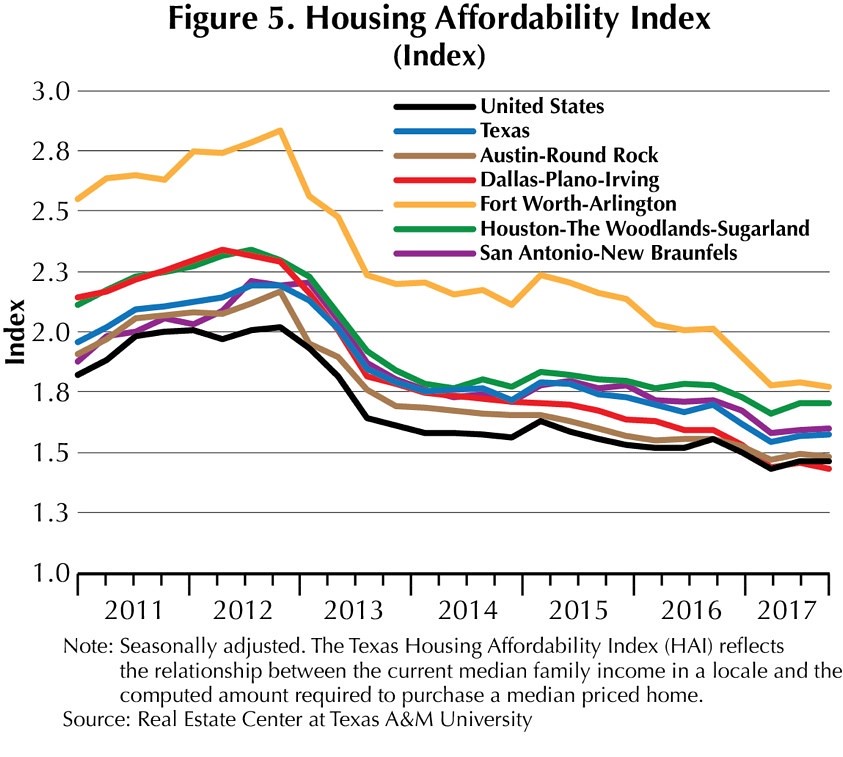

As a result, Texas housing is less affordable, particularly in certain metros. Dallas, according to the Real Estate Center’s Housing Affordability Index, suffered the steepest decline in affordability, while Austin was a close second, followed by Houston. Fort Worth dropped as well but remains the most affordable and San Antonio had the smallest decline in affordability since 2011.

Worryingly, single-family permits in Texas remain below highs recorded during the U.S. housing boom. Despite strong demand for single-family homes since the end of 2011, building has been limited, something exacerbated by increased local government-imposed impact fees, lot costs from regulatory processes, and tight credit for land development.

Initially during the housing recovery, vacant, developed lots were plentiful. Supply dwindled in most major metros as delays in land permitting and shortages of skilled construction workers extended lot delivery times. Available lots fell consistently from 2011 through 2013 in Texas’ major metros (Figure 6). Total lot supply appears to have stabilized and in first quarter 2016 stood at around 20 months supply or more in most major Texas metros, signaling a nearly normal market. Austin and DFW are the exceptions, with supply remaining somewhat tight below 20 months.

The decline in lots has been particularly evident in the under $200,000 price range. Lot supply for housing at this price point is tight as higher land, labor, and material costs have shifted developers and builders from entry-level to higher-priced homes.

Growth in Texas residential construction employment has been slow despite strong statewide job gains. It took Texas about eight and a half years for jobs to reach its pre-Great Recession high of 50,550 workers, registering 900 more jobs in March 2017. This slow labor recovery was partly due to the shale oil boom, which created nonresidential construction jobs such as downstream energy plants and offices.

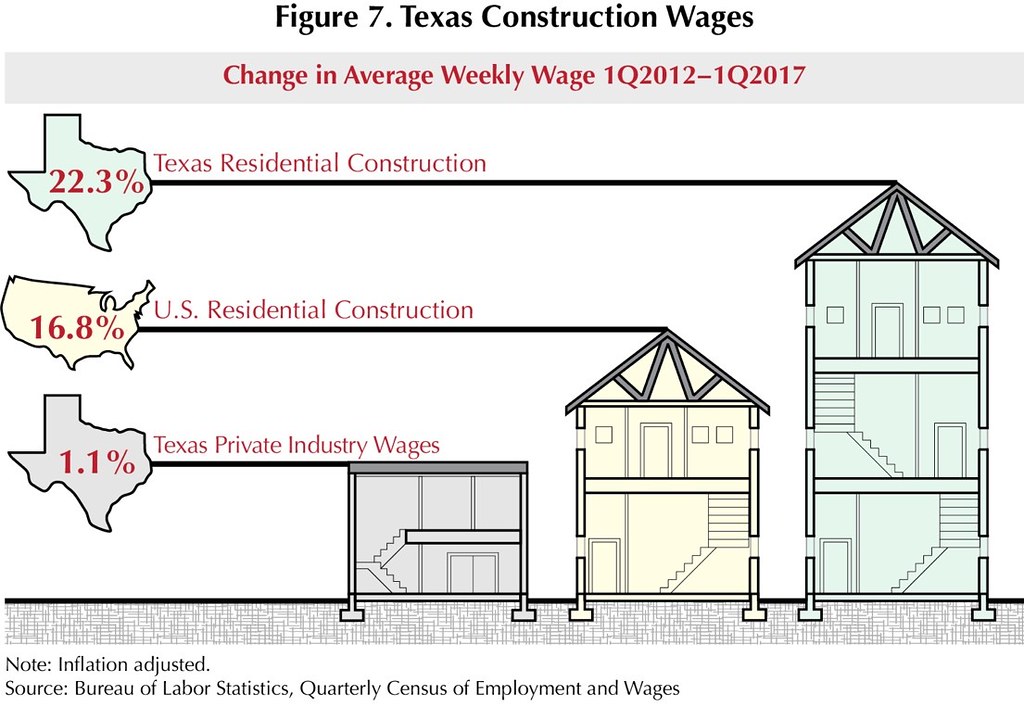

Labor Constraints Drive Costs

Strong demand for single-family homes combined with a tight construction labor market has resulted in stronger wage growth in residential construction in Texas than in the nation. Inflation-adjusted average weekly wages in residential construction climbed 22.3 percent from first quarter 2012 through first quarter 2017. Meanwhile, residential construction wages in the U.S. increased 16.8 percent, and Texas’ total private industry wages were up 1.1 percent (Figure 7).

Affordability an Issue Going Forward

Entry-level Texas homes constitute a smaller share of the market today than they did when the housing recovery began following the Great Recession—a result of unprecedented home-price appreciation. The accelerated price gains are due to the constrained supply in the presence of strong housing demand.

After the Great Recession, the lack of developed lots caused by financial constraints on commercial loans for land development and regulation by local government authorities affected homebuilders’ production capabilities. The lack of lots has pushed up prices for developed land creating an incentive for a homebuilder to build more expensive housing to make a profit.

Anecdotal evidence suggests small homebuilders are hurt the most as they must purchase land from third parties at higher prices. Major homebuilders, on the other hand, can purchase and develop their own land. In addition, labor constraints for skill labor has put pressure on homebuilders to supply new housing, also pushing up costs.

If Texas’ housing supply dynamics do not change as the state’s economy grows, the state will lose some of its comparative advantages in affordable housing. It may be far from the drastic situation in California, but should be leery of anything that puts the Lone Star into a similar trajectory.

Dr. Luis Torres is the Research Economist at the Real Estate Center Texas A&M University, which focuses on real estate economics, regional economics, macroeconomics and applied econometrics. Formerly with Mexico's central bank, Banco de Mexico, Luis previously served four internships with the El Paso office of the Dallas Federal Reserve. Luis understands the workings of central banking, a key driver of U.S. and world economies.

Photo: La Citta Vitta, via Flickr, using CC License.

Texan experts integrity is admirable

It is always heartening to see the genuine concern expressed about any loss of housing affordability in Texas.

Here in New Zealand, we have had most politicians denying for more than a decade that there is any problem, as the median multiple in Auckland has risen through 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10. Even the politicians who have been promising reform, are now talking about getting "affordable housing" built in the form of townhouses "below $650,000" and stand alone family homes "below $800,000".

"Tear-down" houses in old suburbs are commonly over $1,000,000 just as in Vancouver and Sydney. Bear in mind that Auckland is comparable to Indianapolis and Nashville in population, so it is probably the smallest and economically-weakest absurdly-expensive city in the Anglo new world.

So this New Zealander feels like spewing in sheer jealousy at the genuine concern displayed by TX advocates and politicians, when there is a lack of sub-$200,000 houses in boom cities like Houston.

Things to point out in the “we should be so lucky” category, is that growth in the number of households in TX has been 1.6% per annum and the number of houses has also grown by 1.6% per annum, over a sustained time frame, which is totally different to markets distorted by utopian urban planning, where the problem is always relentless undersupply of housing units.

Household income growth in TX has been running at 2.8% per annum - although this has not kept up with house price inflation, TX is obviously are not in the condition of fiscal sabotage where a bubble in house prices is accompanied by flat income growth - as exists in Australia, NZ and Canada.

Also indicating a properly adjusted market in TX: incomes for construction workers have risen 22% in five years; the share of “increased demand” captured by labour is not completely crowded out by incumbent site owners zero-sum gains. NZ has had a worsening housing shortage, a price bubble, construction companies going broke, and construction workers paid appallingly low, all at the same time. In fact builders have been leaving the country because prospects are so poor.

We are watching anxiously to see which way TX goes in the long run. I know experts in TX who suspect that the powerful evil rentiers in property and finance are deliberately trying to starve the development sector in TX of funding because the TX model for development and competing land rent down, is such a “shining light on a hill” against their program which has been so successful in so much of the rest of the world.