This summer, five different immersive Van Gogh opportunities are circulating in dozens of cities around the world, including Detroit, Buenos Aires, and Perth, Australia. If you live in one of the cities that has (or soon will be) hosting one of these exhibits, you have no doubt been bombarded with social media promotions, many involving insufferable “Gogh” puns: “It’s Time to GOGH to see Immersive Van Gogh!” “It’s Safe to Gogh!” “Like Yoga? Try Van Goghga!”

How should this phenomenon be assessed? Popular reactions fall broadly into two categories: 1) excitement about seeing Van Gogh’s work projected, illuminated, animated, and scored or 2) disdain for the flashy, costly exhibits as an Instagram era substitution for genuine art appreciation.

I’m in a third camp; I’m fascinated by the history and appeal of these exhibits, and I also wonder what they can tell us about the relationship between art, social class, and work.

Immersive art exhibits have been around for nearly two decades. The Dali museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, for example, has been showing “Van Gogh Alive” since 2011. In 2017, MOMA offered a hugely popular immersive version of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” Beginning in 2021, larger cities like New York, Chicago, and LA had multiple competing immersive Van Gogh exhibits, while in dozens of other cities there was at least one version of immersive Van Gogh. More than 5 million tickets have been sold worldwide, and, with ticket prices averaging $35 a piece, that’s at least 175 million dollars in sales.

The tipping point may have come in early 2020, when home bound Netflix viewers watched as Emily in Paris visited an immersive Van Gogh exhibit. Immersive art exhibits were not designed with the pandemic in mind, but in 2021 immersive Van Gogh became the most profitable form of in-person entertainment in the US.

What makes digital art immersion so popular? Part of it might be the experience of being out in public with a large crowd, especially after so many months of being confined. Josh Jacobs, one of the creators of Immersive Van Gogh, explained that he was inspired by “collective action. And the idea that experiences change based on the people who are going through it together.”

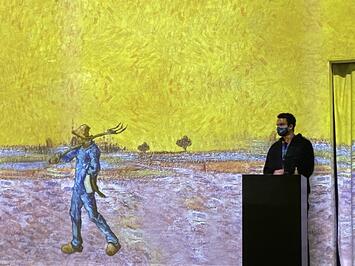

I had my own immersive Van Gogh experience in 2021. During a low point in Pittsburgh’s viral transmission last November, I entered a large hall in a defunct factory on the Southside of Pittsburgh. Van Gogh’s paintings, enlarged to the size of the two-story building, wavered and wafted, appeared and disappeared. Sometimes a cicada or a flock of birds from one of the paintings was animated, flapping their wings toward the ceiling. Iconic songs such as Edith Piaf’s “On, Je Ne Regrette” and more avant-garde works by the Italian composer Luca Longobardi accompanied the images. In a time of doomscrolling and social media distraction, immersive Van Gogh gave me a sense of complete absorbtion, similar to that of an escape room.

Read the rest of this piece at Working Class Perspectives.

Kathy M. Newman is an Associate Professor of English at Carnegie Mellon University and author of Radio-Active: Advertising and Activism 1935-1947.

Photo: Two workers in the Immersive Van Gogh exhibit in Pittsburgh, by Kathy M. Newman.