Finally, an important turning point has been reached for Australians in the housing market: on 22 April 2010 the Council of Australian Governments endorsed a new housing supply and affordability agenda.

The shift in attitude is long overdue. The population of Australia has passed the 22 million mark and is growing at 2.1 per cent per annum. Until now, planning policies based on higher densities have been seen as the solution for this population increase. Such policies are variously euphemistically termed “smart growth”, “urban consolidation” or, more recently, “urban renewal”.

The deleterious results of high-density policies on both people and the environment are becoming more and more apparent. Australian cities, especially Sydney, are starting to exhibit the downside effects of what might be the most aggressive high-density policies in the world. The general public has not yet comprehended how tight the link is between these restrictive planning policies and the increasing prevalence of community problems.

The Australian strategy of high-density has had two components. The first has been to artificially strangle the land supply. Residential land release in Sydney has been reduced from a historic average of 10,000 lots per year to less than 2,000, thereby radically reducing the number of dwellings available from greenfield sites.

The second component of the high-density strategy has required each municipal council to submit a rezoning plan that increases population density to government satisfaction; otherwise, that municipality is adversely impacted. These tactics force high-density onto communities originally designed for low densities.

Smart-growthers claim a plethora of benefits resulting from high-densities. But any clear-headed examination shows that high-density is detrimental to the public good. Greenhouse gas emissions per person are greater in high-density. The policy overloads infrastructure; choking traffic congestion and longer travel times result. Sewers overflow, electricity supply reaches a breaking point, and there are chronic water shortages. Concrete, tiles and bitumen replace trees, gardens and public open space. Sustainability is adversely affected.

And, of course, high-density policies create land shortages that result in unaffordable housing. This is the darkest side to the impetus for Smart Growth. The resulting increase in the overall cost of housing is sobering. Even the global financial crisis had very little effect on house prices in Australia. Prices continue to rise, and the Australian Federal Government has become concerned about the impact of increasing housing costs on the economy. The Governor of the Australian Reserve Bank has said that the price of a marginal block of land is too high for a time when interest rates are low and credit is available , and similar sentiments have been expressed by other officials.

Time series data for Australian cities shows a strong correlation between inadequate land release and excessive housing cost. The land component of the price of a dwelling in Sydney has increased from 30% to 70%. It is apparent that strangling the release of land on the outskirts in order to force high-density has resulted in a shortage and, in the face of ever-increasing demand, the price of land has risen dramatically.

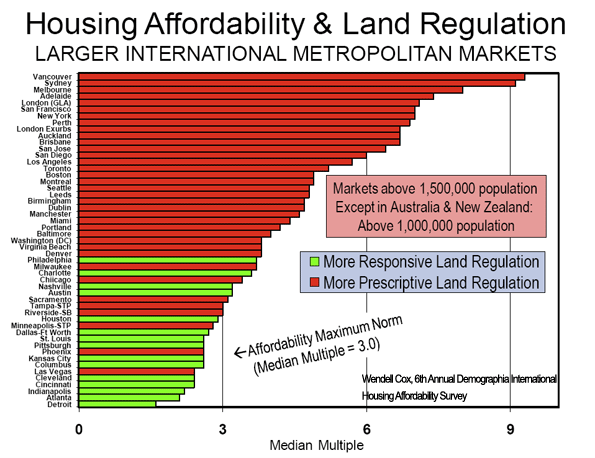

The 6th Annual Demographia Housing Affordability Survey of six countries portrays a widespread relationship between high housing cost and overly restrictive planning. In the chart below, housing cost is measured as years of family income needed to purchase a house. This year the picture is somewhat complicated by the collapse of the housing bubble in some prescriptive jurisdictions resulting in a substantial reduction of previous high prices.

Median house price divided by gross annual median household income.

Only about seven per cent of Australians wish to live in apartments. In spite of this, smart growth policies have resulted in apartments being the only type of housing available to most new entrants to the housing market. These apartments command higher prices than otherwise would be the case, due to an inadequate supply of competing single-residential housing resulting from the scarcity of available sites. This provides the potential for apartment developers to make large profits. Such profits provide the resources for developers to make large donations to the political parties.

Over the previous five years, the ruling New South Wales Labor Party received donations from the development industry of $9 million, while the Liberal opposition party netted $5 million. These donations exceeded the total contributions to all political parties over the same period from the gambling, tobacco, alcohol, hotel, pharmaceutical and armaments industries combined.

Numerous documented cases show a large donation being made shortly before permission is granted for a particular development. In response to long-term escalating public anger, the New South Wales Government in December 2009 passed legislation to prohibit donations from property developers. However, the public cynically consider this will not solve the problem and that “donations” will be given in other ways.

In the face of criticism, state governments maintain that recent land releases have been sufficient. The New South Wales Minister of Housing has stated that land for 131,000 homes has been released in Sydney. Yet the shortage continues to get worse. One reason is the tortoise-like progression of the rezoning process.

Another is market manipulation. As the Demographia survey points out, governments flag well in advance which greenfield areas will be zoned for developments. Sellers then realise they are cushioned from competition and can command higher prices for their land. Purchasers – developers -- know they can pay substantial premiums compared to what would be the case if land release were not so predictable.

It appears that developers (both government and private) then carefully control the rate at which these greenfield sites are made available to home buyers. It has been reported that the Melbourne government development agency is sitting on a stockpile of 25,000 house blocks that have been zoned for residential approval, but is selling just 700 per year. Private developers and landholders currently hold almost 70,000 house blocks, yet only 1400 of these are available to the market . In the current situation of high demand, it is evident that housing land is being drip fed onto the market, thus keeping prices high.

The Council of Australian Governments seems to have taken cognisance of this situation, as the review will examine large parcels of land “to assess the scope for increasing competition and bringing land quickly to the market”.

The Council’s review indicates a welcome change in thinking. Up to now it has not been generally recognised that planning policies are a significant factor in excessive housing cost. Other adverse effects of these policies still need to be acknowledged. One hopes that this review will represent the beginning of a broader appreciation of the downside of high-density policies.

Photo: A strip of 'Sydney Lace'in Balmain, Sydney, New South Wales

(Dr) Tony Recsei has a background in chemistry and is an environmental consultant. Since retiring he has taken an interest in community affairs and is president of the Save Our Suburbs community group which opposes over-development forced onto communities by the New South Wales State Government.

The bubble is already re-inflating in AU cities. Are we next?

I was a little surprised and at the same time concerned about the recent news I've been reading about Australia and what appears to be a new housing bubble in most of their major cities. Incredible because Australia actually had a severe housing bubble prior to ours that peaked sometime around 2003-2004, about 3 years before ours in the US. The stories coming out lately mention 20-30% appreciation. The prices in places like Sydney are in San Francisco territory as we speak thus having that level of appreciation is almost unfathomable.

My concern is that I hope we aren't seeing a repeat of the last pattern where Australia wound up being the opening act to our own housing bubble here. Just like Australia a lot of most bubbly US cities didn't have anything close to a significant correction. I'm not familiar with what the Australian government did during the bubble collapse there but the US government has thrown everything they can to keep the bubble inflated.

All I can say is that we're planning on leaving San Francisco in 6 months. It might be a good time to get away before we get our own bubble re-inflation.