Like the rest of us, I pick over the stock market’s runic inscriptions to find meaning in earnings reports, ratios, analyst reports, and trend lines, hoping to divine the traces of an orderly world—something it clearly is not.

In modern nations, especially the United States, the averages of stock exchanges have, at least psychologically, become synonymous with the national pulse and well-being. America was a happier and more prosperous country when the Dow Jones industrial average was above 14,000, as opposed to its current levels of around 10,000. To be more precise, the country is about thirty percent less happy than before the crash of 2008.

What has accounted for the changes in the market, not to mention the selloff in the national psyche?

A favorite book about the market psychology of the U.S. economy, Clement Juglar’s “A Brief History of Panics,” was published in 1916. It makes the point that since the founding of the republic, the country has experienced booms and busts roughly every ten years, and that the market has three phases: Panic, when assets get dumped; Liquidation, a period of deflation, where we are now; and Prosperity, when credit is easy, people buy things, and stocks go up.

For the moment, the stock market, like the economy at large, is in Liquidation. Few investors wake up in the morning with the idea of acting on a tip that they heard whispered at a club dinner. Buying stocks is something that your grandfather did, probably in a drab suit and a kind of Jack Ruby hat.

Are stocks a good deal? The overall exchange is in the doldrums — real estate is bust, the only new employer is the Census Bureau, banks are black holes. Dow Theorist Richard Russell advises his subscribers, “We’re now in the process of building one of the largest tops in stock market history. The result, I think, will be the most disastrous bear market since the ’30s, and maybe worse.”

But unless you are a gold bug, even now stocks are better deals than the alternatives: lending your money to a wobbly government (T-bills and bonds to insolvent nations), leaving it on deposit at a bank (zero return, and bank balance sheet risk), or flipping condos in Miami (do you really want to be a landlord?).

I still believe there are quality stocks that are cheap enough to buy, and, chosen well, stocks throw off cash, offer an inflation hedge (those that can reprice their products easily), and can be bought in any amount. In high school I invested $180 in an obscure company my father had never heard of, Toyota. Wish I still had it.

The reason stocks are languishing, however, is that most investors feel burned by the collapse. They bought things that their brokers, their friends, or their golf buddies suggested, and those financial instruments went up and then down, for reasons few understand.

Take GE. When it was $57 a share, and growing at twenty percent a year, CEO Jack Welch was a genius and writing books with modest titles like “Leadership” or “Winning.” The company was “well positioned,” and, according to most brokers, a client's portfolio “needed a little” for the long term. Anyone who had it made money.

Now it’s $15, and is probably a better company than when it was at $57, but nobody wants any of it. Welch is remembered as just another guy who raked in millions in stock options, treated the company like a honey pot, and dumped his wife for a hot editor.

Even at $15, however, GE is still expensive to buy. It’s price-earnings ratio is twelve times (meaning you give them $12 for every $1 you get back in earnings), and the yield is 3.2 % (what you earn while holding the share). GE would actually be a good deal when the stock price drops to $10, the P/E is eight, and the yield is 5.4 %. From that low entry point, you will stay “in the money” for a long time.

What ruined the stock market in 2008? I would argue that the government’s demand for funding collapsed the pyramid schemes on which modern investment banks, not to mention stock markets, were built. In Juglar’s phrase, it was a panic of liquidity.

The federal demand to fund the U.S. deficit and the suspicious balance sheets of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac dried up the easy money that had previously allowed the Lehman brothers to party on in commercial real estate. In turn, the stock market ran up on the fumes of bank and personal leverage, much drawn from home equity. Now that money is propping up mattresses.

Much of the stock market collapse, however, is because buyers will only pay a low premium for shares. A stock that once traded at twenty times it earnings, but is now trading at twelve times earning, will have lost almost half its market value. Ironically, the underlying fundamentals of such a company may be little changed.

Look at Johnson & Johnson. Most of its key ratios have improved steadily over the last ten years, yet at the same time it’s stock price is down, because investors will not pay the multiple that they paid previously to own it.

In 2007, J&J earned $3.63 a share, when it traded around $67 (that’s a P/E of eighteen). Now it brings in about $4.84 a share, yet the company’s stock price is $58. It still sells for a premium of twelve times, which is low for Johnson & Johnson, but not the kind of bargain that would tempt Warren Buffett, who wants the companies he buys to sell for a P/E under ten.

To make money in the stock market, forget about “market sentiment,” “investor psychology,” or Jim Kramer’s “Mad Money.” Instead, think of the stock market as a mall that has high-priced boutiques, discounters, mom and pop stores, and even Wal-Mart. Who in America doesn’t understand malls?

When you buy from the elegant boutiques (stocks in favor, selling at high premiums, with brands that everyone wants, like Google), know that you are indulging an impulse, fashion buy, and that someday you may be trying sell the equivalent of last year’s Gucci loafers on eBay. (“Common stock, hardly used, a lot of buzz about this co., you pay shipping.”)

In the stock-market mall, however, there are other shops, with companies that no one wants or has heard off, that will let you share in their profits, treat your money with respect, and even pay you dividends while you own them. Search for companies that have a sustained record of profitability, regularly increase their dividends, have relatively low debt relative to their capital, employ drab managers who drive Buicks, and have diverse products with broad appeal.

Never buy a stock that has naming rights to a professional stadium.

It helps if this company, for reasons beyond its control, has been “beaten up” in the stock market and if it trades at a historic low premium. In summer 1982, GE traded at a P/E of five times its earnings. When I started in banking, banks sold for less than book value, and a P/E of about seven times. At their peak, some traded at 32X earnings.

If you are nervous about owning stocks, only buy a few, in companies that you can study and understand. Sell them the moment they reach your “selling price,” which is almost the moment when you look at your statement and think, “That’s doing okay.”

In looking at the cycle of the American economy and its markets, Juglar saw Panic lasting a few months to a few years, Liquidation going on for several years, and Prosperity running five to seven years.

Think roughly of the bull markets between 1982-89, and 1996-2001, and 2003-2008, and they reasonably track Juglar’s timetables. Yes, the current phases of Panic and Liquidation are no fun, but the pattern was familiar in 1916.

Juglar's investment advice: “Buy when the decline caused by a panic has produced such liquidation that discounts and loans, after steady and long-continued diminution, either become stationary for a period, or else increase progressively coincident with a steady increase in available funds; and sell for converse reasons.”

I prefer the more shorthand market expression: “The only time to buy a stock is when you feel like throwing up.”

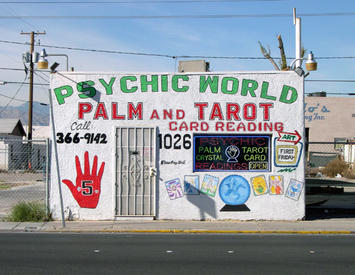

Photo by roadsidepictures of Psychic World, Las Vegas, Nevada, built in 1938.

Matthew Stevenson is the author of Remembering the Twentieth Century Limited, winner of Foreword’s bronze award for best travel essays at this year's BEA. He is also editor of Rules of the Game: The Best Sports Writing from Harper's Magazine

. He lives in Switzerland.

Reading Tea Leaves is as good a method as any.

Information on how to read them is on the web. Just get some loose tea, make some tea, and then drink it leaving the leaves and interpret away. For the Greek debt crisis I wanted CNBC to send one of their reporters to Delphi in Greece and consult a re-set up oracle to see what she would say.

One could be Roman about it but PETA would object (cut open a chicken and do harspex). All are as good as the analysists that CNBC runs, in its BiPolar way. J.P.Morgan the Banker was right when he said that the market would fluctuate.

Everyone thinks they can outsmart the market when in the long term (and indeed in the short term also) at best 1/2 can beat the market. Since that is likley less due to the friction of the market so that the house can get its cut, the number rapidly decreases over time. So just like I remarked a few years ago on the Ethernet versus Token Ring battle, don't fight the market you will loose in the long term.