Robert Sarnoff , the CEO of RCA before it was absorbed by GE, once said, “Finance is the passing of money from hand to hand until it disappears.” That process is very clearly defined in The Age of Greed by Jeffrey Madrick. It recounts, in concise terms, how a few dozen individuals—some in the private sector, some in government--brought us to our current economic pass, in which finance seems to have been completely detached from life. Names from the past come back, and their crimes are explained. Ivan Boesky, Michael Milken, and Dennis Levine look guiltier in the retelling than they did in the newspapers at the time. And in this telling, the philosopher king of the new finance was Walter Wriston, CEO of Citicorp.

I wrote for Wriston and other senior managers of Citibank from 1980 through his retirement in 1984, and for his successors through 1991. My colleagues and I were charged with helping Wriston make the case that the financial regulatory regime that was put in place during the Depression was obsolete. Let me make it clear: I was a footnote, although I occasionally run into old acquaintances who still shake their fingers at me.

Madrick’s Wriston is by far the book’s most compelling character. As with all the other subjects, there’s a smattering of armchair Freud, although most of the political figures who make appearances here escape their two minutes on the shrink’s couch. Wriston’s psyche was more interesting than the insecurities of Ivan Boesky and Sandy Weill, to name just two; his university-president father Henry Wriston despised the New Deal as it was happening, and imparted that attitude to the son. Henry then remarried too quickly after Walter’s mother died for the son’s taste, and they became estranged.

But there’s more to Wriston than you read in Madrick. He was a restless intellect, impatient with field of diplomacy he had studied for before World War II, and after taking a job in banking, which he once wrote seemed like, “the embodiment of everything dull,” found a vehicle for exerting his imagination, and then for fulfilling his ambitions. The First National City Bank, later to become Citibank and Citicorp, and then Citibank again, had inspired imperial dreams before. Through a series of mergers it became the biggest bank in the biggest city in the country. When trade followed the flag around the world, Citibank’s precursors were right there with it. During the Roaring Twenties, Charles Mitchell dreamed of a “bank for all”, the forerunner of Wriston’s vision of one-stop banking, although Mitchell’s stewardship ended with a trial (and an acquittal) after the stock market crash and the Pecora hearings in the early ‘30s. While the bank had social register threads running through its history—when Wriston started the president was James Stillman Rockefeller, descended both from the Stillmans and the Rockefellers, married to a Carnegie—the patrician elements always had hungry outsiders around to push the envelop of banking practice. When Rockefeller was chairman, he had a president named George Moore, and Wriston was his protégé. However, Moore was too frisky for Rockefeller, and when a successor was chosen, it was Wriston.

Wriston hung a portrait of Friederich Hayek on the wall of his office. He was a reader. When Adam Smith became the Holy Ghost of the Church of Deregulation, Wriston’s top writer (and later my boss) was the man who actually edited The Wealth of Nations for the Great Books. When I was new there, I asked one of the bigshot corporate bankers which great thinkers he liked to quote in his speeches. He answered, “The only person who can get away with that is Walt Wriston, and I’m not sure he can.” Wriston’s ambition may have been shaped by philosophy, but he achieved it with tactics and strategy that sprang from a contrary nature as much as by the force of his ideas, and Madrick recounts that. He wanted his bank to be valued like a growth stock, and promised analysts 15% a year return on equity—not a recipe for safety and soundness.

Whether it was inventing financial instruments to get around interest rate restrictions, making outsize bets on railroad bonds and New York City bonds, creating the Eurodollar market, blitzing the country with credit cards, or wholesale lending to developing countries to recycle petrodollars, Wriston had a knack for making money when the economy was right and then challenging the government to deregulate in time to accommodate his losses. Personally, I think that before the bank was too big to fail, it was too big to succeed.

Looked at now, there’s something quaint about these investments. At least they had to do with real things, like trains, oil, municipal governance, and the ostensible aspirations of people in emerging markets, although they were mostly oligarchs and autocrats. In Madrick’s account, Wriston was dismissive of the government’s capacity to efficiently recycle petro-dollars, among many other things, and contended that his loan officers knew more about their corporate customers than anyone else did, which would enable them to safely make riskier loans than capital standards would permit. We all know how that turned out.

Wriston was a real visionary. To underscore his then-revolutionary idea that information about money was as important as money itself, he bought a transponder on a satellite to carry the bank’s data stream, and then put a satellite on the cover of the annual report. Theoretically, all that proprietary information made it hard to hide bad news about a company’s finances or a country’s; executives and prime ministers beware of poor management! He was undoubtedly the first bank CEO to anticipate what Moore’s Law—quantifying the exponential growth of computing power—would mean to business and society. Unfortunately, that power is exactly what enables the hollow finance we have today.

Reading Madrick’s book was like watching my life pass before my eyes, including the parts I slept through, and it certainly brought me up to date on events that happened long after my eyes glazed over.

It reminded me that when Wriston ran it, Citibank was fun to work for, as jobs in tall buildings went. My closest colleagues were well-educated and witty refugees from college faculties. The bank’s historian worked closely with us, and we learned the secrets that never made it into the deadly official history, such as the fact that one of Wriston’s predecessors kept a house in Paris, where he was known among the haute couturiers as le bonbon, or that when the Titanic went down, some hard-money banker had written to customers that there was good news—the loss of all the paper currency aboard would strengthen the dollar. Wriston set the tone: History counted, an attitude that wouldn’t survive the cost-cutting that came later. Wriston was renown for his sharp needle, but when I found myself in his office with the portrait of Hayek staring down, he seemed to enjoy the relief from the routine pressures of his job. I always had some kind of bleeding heart question based on current events, and he always had a sharp, witty retort.

He was also a citizen. When the City of New York had its own financial collapse in 1975 (“Ford to City: Drop Dead”), Wriston represented the commercial banks on the committee charged with rescuing the city’s finances. One of the bank’s economists assigned to work with him saw the beating Wriston took every day at the hands of the municipal unions and asked why he carried on. He answered, “Because I live here.” I wish some of the new financiers who have benefited from the work Wriston did would exhibit some evidence that they felt that way about the city. About the country. About the world.

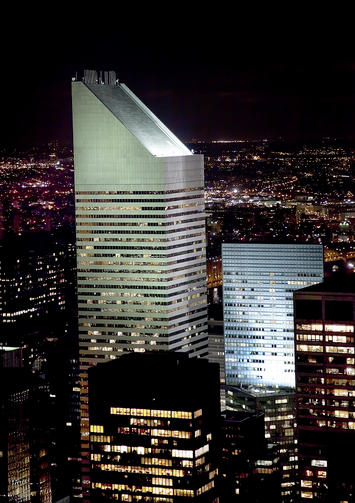

Photo: Bigstockphotos.com; the old Citibank and newer Citicorp buildings.

Henry Ehrlich no longer writes for bankers, although he still likes money. He is editor of

www.asthmaallergieschildren.com, and co-author of Asthma Allergies Children: a parent's guide.

Citibank, Citizen Wriston, And The Age of Greed

I really enjoy. The thing I like most farming but I have been taking on new things lately. I've been focusing on my website for some time now.

Take a look here:http://howdoyougrowtaller.tumblr.com/post/60517831905/grow-taller-4-idiots-review-darwinsmith-medical

hollow finance

We definitely do live in an age of hollow finance. As our country becomes more of a service-oriented republic that is eventually built upon credits that are transferred via the web (as many credit analysts believe) it's easy to see all of that evaporating by the simply click of a mouse. We live in an age where we have intellectual property and no way to rightfully value it.

CEO Greed

Henry Ehrlich is one of the nation's best speechwriters. Can he help it if his speeches were so convincing? He had no trouble convincing President Clinton that is was safe to repeal of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act. Never mind that this was a favor to his Treasury Secretary, the former CEO of Goldman Sachs and future Vice Chairman of Citibank. But neither Henry nor Clinton -- nor possibly even Wriston himself, could foresee that once the government tears down the Chinese wall between commercial banks and investment houses, another wall needs to be erected -- a wall of political protection. Because when you’re too big to fail, you’re clearly too big not to pay bonuses or legal bribes to politicians. Wall Street’s stupendous bonuses are illustrative of the degree to which shareholders have lost control of the firms they own to CEOs.

And the bigger they are, the harder they are to control. But simply being big – so big that the firm’s failure is destabilizing – was never addressed in our anti-trust laws. And it’s not easy to address now. When heiress Hetty Green removed her deposits from the Knickerbocker Trust Company, the bank went under, triggering the Panic of 1907. Knickerbocker wasn’t a large institution even by the standards of the day. But its failure was destabilizing for the same reason AIG’s failure would have been destabilizing. Who could have imagined that that AIG would be the linchpin of the world economy? But the it was the insurer’s relationships with giant counterparties to its derivative deals that rendered its failure unthinkable.

Needless to say, these linkages were meant to insure the CEO and the reckless undertakings that he spawned. No one ever helped his victims, who are linked to the economy at large. These people lost close to $10 trillion in stock market and housing wealth – many ending up both homeless and jobless. And later, when rates on many adjustable rate mortgages were reset upward, adding an average of $450 to monthly payments, defaults doubled and the US was in a foreclosure crisis.

We are paying for CEO greed. While unemployment and underemployment were earlier the results of off-shore production, now they result from CEO recklessness in the financial markets. Officially, the current unemployment rate is the highest it has this far into a recovery since the 1940s. But as we all know it’s worse than that as the definition of unemployment changes when the unemployed become discouraged and stop looking for work. Unofficially, the unemployment rate is about 16 percent. But the official numbers keep track only of those receiving unemployment benefits. The government is simply too embarrassed to count those workers who still don't have a job and would take one if they could get it; and even if you're still looking after 6 months, a sign of true hardship, they stop counting. To further veil the numbers, they arrange the "job creation" statistics so that only the number of W-2's are counted. This idiocy doesn’t consider if the W-2 represents full-time or part-time work. Hence, if someone loses a full-time job with benefits and has to take three part-time jobs to get by (without benefits), the statistics would show that the economy created two new jobs.

Of course, those who get even part-time work are lucky. Over 6 million are officially out of work, having been unemployed for more than a year. This is the largest in recorded history. When discouraged workers are added to the list, the number swells to over 14 million. Some of us wonder how some 14 million unemployed suddenly disappeared from the face of the earth. They have been erased from the national consciousness like the hobos who rode the rails during the first Great Depression.

Is it any wonder that most companies have replaced the term “performance bonuses” with “retention bonuses” That’s how Citigroup described the $23.2 million award it made to CEO Vikram Pandit. What it was retaining was a string of bad performances. In April 2007, Pandit sold his hedge fund to Citibank for $800 million – a fund that failed so miserably the bank had to close it down.

CEOs have only two approaches to business– fire more workers and give me more money. It is beyond them to try to create their way out of a problem. In a letter to Parade Magazine during the fourth year of the economic crisis, Queen Latifah, a truly creative entrepreneur, wrote, “People in business kind of freak out looking at the economy. I guess if you’re used to having all the money in the world, you don’t see how to makes things work in bad times. But if you built things from the ground up, you’re used to creating with less. We saw it coming and looked at it as a time to be creative. We’ve gotten so much accomplished behind the scenes in the last year – in film, music, television, Web content, food, beverage and clothing – that I can’t wait to see things come to fruition. The good thing about doing what I do is that, if it’s not already there, hopefully, I can create it.”

Clearly we need more CEOs like Queen Latifah.

BS found in BSDetective's comment

Ehrlich is clearly not writing a straightforward review but instead providing a small and affectionate portrait of "Wriston: The Man" that would not necessarily appear in an expansive work of popular history like The Age of Greed. Your inability to recognize this is surprising considering that the article doesn't bill itself as a review at all.

Furthermore, Ehrlich's apparent disapproval of the bankers' poor corporate citizenship can hardly come as a surprise considering the economic collapse of the last half-decade. Your own claims about Ehrlich's politics are equally puzzling. You seem to possess an unparalleled ability for mind-reading in your helpful translation of Ehrlich's apparently innocuous reminiscences about his former colleagues.

Finally, most confusing is your anti-regulatory pronouncement at the end. It seems that you disapprove of the idea of financial regulation because its American iteration has done more to preserve wealth for the few. And you call Ehrlich a socialist?

And as long as we are complaining about copy-editing: you would do well to review the difference between "possessive" and "plural" nouns (re: your use of the word "enemy's" when you meant to say "enemies.")

What??

Does anyone proof-read anymore? Besides being pocked with grammatical errors, this book review makes no sense. What is Mr Ehrlich's point in all this except, perhaps, letting us know that he was once employed in a job that mattered and that he's a socialist.

With absolutely nothing to back up his leftist innuendo, comrade Ehrlich claims government regulations as a necessity are a foregone conclusion, Hayek is somehow a symbol of corporate greed, Henry Wriston was evil because he saw the folly of the "New Deal", that President Ford told New York to "Drop Dead" and a host of other pinhead insinuations about bank operations then and now.

Mr Ehrlich exposes his anti-American, anti-capitalist leanings when he gushes about working for Wriston back in the good ol' days, when he played patty-cake with his "well-educated"(read: communist), "witty" (read: boorish) college refugees (read: bed-wetters).

Mr Kotkin and his lazy brain-trust at PSG, are the last, if we're lucky, of the liberal morons who were never bright enough to consider that the reason we have moved from one financial disaster to the next is BECAUSE of Fed regulations.

Since the turn of the last century, when Teddy Roosevelt started protecting his rich pals from their rich enemy's, the Federal Government has made it easier and easier for the rich to game the system. And the reason we never learn the folly of government regulation, is because there are so many stupid people, like Kotkin and Ehrlich, perpetually blind to the FACT that the Federal Government belongs to the rich and powerful. Exactly as our forefathers, you konw, those evil slave owners, warned would happen with an all powerful Federal government.

America the beautiful, land of mostly morons.