As traffic levels decline nationally in defiance of the usual state DOT forecasts projecting major increases, a number of commentators have claimed that we’ve reached “peak car” – the point at which the seemingly inexorable rise in vehicle miles traveled in America finally comes to an end. But while this has been celebrated, with some justification in the urbanist world as vitiating plans for more roads, the implications for public policy haven’t been fully faced up to.

Indeed, the “peak car” is antithetical to the reigning urbanist paradigm of highways known as “induced demand.” Induced demand is Say’s Law for roads: supply of lanes creates its own demand by drivers to fill them. Hence building more roads to reduce congestion is pointless. But if we’ve really reached peak car, maybe we really can build our way out of congestion after all.

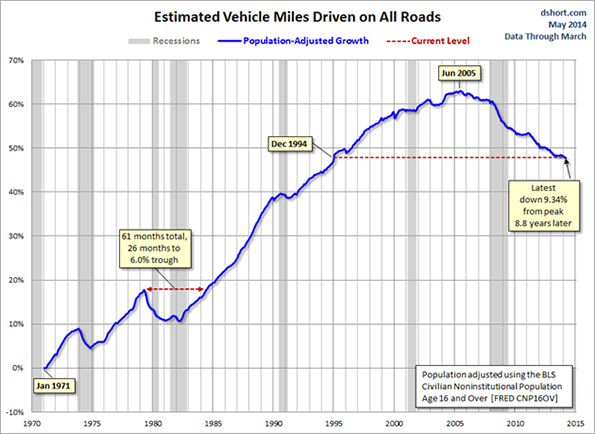

Traffic levels have stabilized or even fallen in recent years. According to analysis by economist Doug Short featured in Streetsblog, aggregate auto travel peaked on a per capita basis in 2005 and has fallen since. Per capita traffic levels are now back to 1994 levels, a two decade rollback in traffic increases.

Population adjusted traffic growth. Image via Doug Short

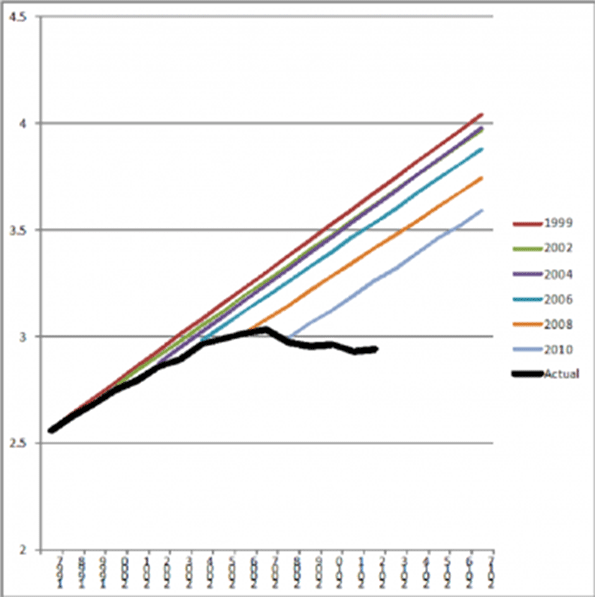

Even looking at total, not per capita travel shows a marked reversal. The State Smart Transportation Initiative, a pro-environmental research center, put together a graph showing how high the US DOT’s traffic projections have turned out to be:

VMT forecasts vs. actual. Source: SSTI

This data is complemented by a slew of recent stories about the poor financial performance of toll roads, resulting in part from traffic falling far below projections. For example, the concessionaire operating the Indiana Toll Road recently went bankrupt. Streetsblog reported that while projections forecasted traffic level increase of 22% in the first seven years, traffic actually fell 11% in the first eight.

Recent traffic declines are a reversal of a long running trend of Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) increases at above growth in population. Some of this is no doubt due to the poor macro-economy. But there are reasons to believe we may be in a new era of traffic growth or lack thereof. Many of the trends that drove high growth have largely been played out: household size declines, suburbanization, the entry of women into the workforce, one car per driver, etc. That’s not to say these will necessarily reverse. But we’ve reached the point of diminishing returns in terms of how many more women, for example, will join the labor force given that there’s already 57% female participation and their labor force participation rate is projected to decline in the future.

This is potentially very good fiscal news, especially given tight budgets. Clearly many of the freeway expansion projects on the books that have been driven by speculative demand should be revisited. For example, the state of Wisconsin has massive investments planned in Milwaukee area freeway system even though the metro area is very slow growth in population. Are these really necessary? Projects in more rapidly growing boomtown regions in places like Dallas, Houston or Charlotte may well continue to make sense. From top to bottom, engineers need to recalibrate their forecasting models to better correspond to reality. And to revisit highway plans accordingly.

So the idea that we need to build fewer roads than we thought is sound. But less attention has been paid to the flip side implications of this. To repeat, the induced demand theory says that there is a more or less infinite supply of traffic, thus any new roadway capacity will be used up shortly, leaving congestion as bad as the status quo ante. Despite peak car, articles touting induced demand as a reason not to build roads continue unabated, including recent ones in Wired (“What’s Up With That: Building Bigger Roads Actually Makes Traffic Worse”) and Vox (“The ‘fundamental rule’ of traffic: building new roads just makes people drive more”). In a world of peak car, where traffic levels are flat to declining on a per capita basis, induced demand no longer holds court, certainly not to the level claimed by those who believe it’s pointless to build roads.

In fact, what peak car means is that while speculative projects may be dubious, there many be good reasons now to build projects designed to alleviate already exiting congestion. Places like Los Angeles remain chronically congested, which has great economic and social consequences, not the least of which is the value of untold hours lost sitting in traffic. While individual projects there might indeed be boondoggles, maybe it’s worth building some of the planned freeway expansions there in light of peak car. In short, in some cases peak car strengthens the argument for building or expanding roads.

On the other hands, many of the regional development plans designed to promote compact central city development and transit may be predicated on an analysis that assumes large future traffic increases in a “business as usual” scenario. Not just highways but all aspects of regional planning are dependent on traffic forecasts. That’s not to say that such plans are necessarily wrong, but clearly revised traffic reality needs to be reflected in all plans, not just highway building ones.

It’s not clear how this will all play out, but urbanists and policy makers of all stripes need to think about the full implications of peak car. At a minimum, the traditional “you can’t build your way out of congestion” rhetoric should be supplanted, at least in most areas, by a more nuanced approach that neither overestimates demand, nor ignores the problems caused by rapid growth in some regions and pockets of congestion in others.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile.

Peak cars

Especially in urban regions we have found the concept of peak cars; in these regions due heavy traffic rush people are suffering from various problems. Therefore in different sector we have found ply overs and better traffic system in order to put a control over the rush problems; it ultimately affect our vehicle's mileage system and affects the engine control system also. I hope the concept of peak car also works and serve a better result to the people.

BMW Repair Walnut CA

No doubt car is an essential

No doubt car is an essential way of communication than other vehicles as it is comfortable. Our environment get polluted due to emission of CO2 from vehicles. So automobile industries try to implement new technology to stop or reduce this.Green transportation and blue technology is the best solution, so go for this.

Mutually Exclusive?

I'm not sure that peak car and induced demand are mutually exclusive concepts. If you build a road along a corridor where there is little demand for travel, it won't be well used (especially if a free alternative exists). Expand the capacity of a highly congested roadway and you will certainly induce more car traffic (especially if it's free). Congested roadways, though, are typically in built up areas, making them incredibly expensive to build/expand and politically challenging to pursue, especially given the infrastructure maintenance costs of our existing roads. As a society, it seems to me that we've made a decision not to build many roads that would significantly induce more car travel. In addition, as you mention, the rise of women in the workforce has leveled off, the middle class is no longer booming, demographics are changing, and the suburban ideal is fading. All of this has led us to peak car. However, I'd bet that if we pumped gazillions of dollars into double decking all of our congested urban highways, I'm sure people would drive even more than they do now, but you'd be hard pressed to find many people who think that that is a good idea.

SSTI

SSTI is a project at the University of Wisconsin, not an environmental advocacy group as the post states.

"Induced demand" is bad????? Only for roads??????

"Induced traffic" always was a fraudulent argument. Most of the growth in traffic was going to happen anyway - women joining the workforce, automobility becoming affordable to people lower and lower in the income distribution, and a boom in the number of seniors with health and independence.

It is a half-truth that cities that build, build, build highways do not "solve traffic congestion". But the cities that DON'T build highways end up with far WORSE traffic congestion; plus the cost-benefit of transit spending is a fiscal disaster compared to the same money spent on roads. In the long term, transit subsidies are just moving a certain number of people around every year, but road "subsidies" are building permanent surfaces on which car drivers PAY THEIR OWN WAY for something like THIRTY TIMES AS MUCH travel per subsidy dollar.

I argue that a typical comparison of cities runs something like this: there are US "automobile dependent" cities that have literally 3 times as much highway and arterial lane-miles per capita as anti-car planning cities like Stockholm; and the TomTom congestion delay per 1 hour of driving at peak is typically 15 minutes versus 45 minutes in the cities like Stockholm and Auckland. VMT per capita might be 20% to 30% higher, and this indicates a kind of logical upper limit to "induced driving".

And the cost of transit subsidies, enabling only 1/30 as much actual travel per $ spent, has to be an bankrupter of finances in the long run, for the anti-car dystopias, plus with the cost of congestion and the foregoing of "demand enabling" in the local economy.

It always DID make sense to BUILD freakin' road space as demand for it grew, and it always WAS likely that growth in car travel would reach saturation eventually! This is not rocket science! It is no different to growth in the use of refrigerators, hot water, and telephones! Roads must be just about the only thing where a weird back-to-front assessment has prevailed. Generally something that does NOT "induce" demand - whether carrier pigeon communication, liquid sodium silicate food preservation or public transit - is rightly regarded as obsolete and superseded by something better. Selecting something as the target of investment on the grounds that it does NOT "induce demand", over something that DOES, is and always has been an evidence of insanity.