Twenty years ago, America’s cities were making their initial move to regain some of their luster. This was largely due to the work of mayors who were middle-of-the-road pragmatists. Their ranks included Rudy Giuliani in New York, Richard Riordan in Los Angeles, and, perhaps the best of the bunch, Houston’s Bob Lanier. Even liberal San Franciscans elected Frank Jordan, a moderate former police chief who was succeeded by the decidedly pragmatic Willie Brown.

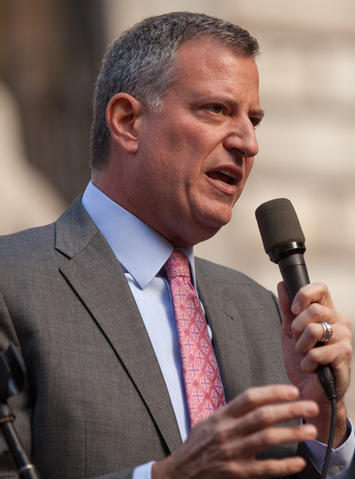

In contrast, a cadre of modern mayors is minting a host of ideologically new urban politics that put cities at odds with millions of traditional urban Democrats. This trend is strongest on the coasts, but is also taking place in many heartland cities. Bill de Blasio is currently its most prominent practitioner, but left-wing pundit Harold Meyerson says approvingly that many cities are busily mapping “the future of liberalism” with such policies as the $15-an-hour minimum wage, stricter EPA greenhouse gas regulations, and housing policies intended to force people out of lower density suburbs and into cities.

For the Democrats, this urban ascendency holds some dangers. Despite all the constant claims of a massive “return to the city,” urban populations are growing no faster than those in suburbs, and, in the past few years, far slower than those of the hated exurbs. This means we won’t see much change in the foreseeable future in the current 70 to 80 percent of people in metropolitan America who live in suburbs and beyond. University of Washington demographer Richard Morrill notes that the vast majority of residents of regions over 500,000—roughly 153 million people—live in the lower-density suburban places, while only 60 million live in core cities.

This leftward shift is marked, but it’s not indicative of any tide of public enthusiasm. One-party rule, as one might expect, does not galvanize voters. The turnout in recent city elections has plummeted across the country, with turnouts 25 percent or even lower. In Los Angeles, the 2013 turnout that elected progressive Eric Garcetti was roughly one-third that in the city’s 1970 mayoral election.

Bolstered by this narrow electorate, liberal pundits celebrate the fact that 27 of the largest U.S. cities voted Democratic in 2012, including “red” state municipalities such as Houston -- but without counting the suburbs, where voter participation tends to be higher. An overly urban-based party faces the same fundamental challenges of a largely rural-oriented one—for example, the right-wing core of the GOP—in a country where most people live in neither environment.

Demographic and Political Transformation of American Cities

City dwellers have historically voted more liberally than their country or suburban cousins, but demographic trends are exacerbating this polarizing impulse. Simply put, the cities that could elect a Giuliani or a Riordan no longer exist. The centrist urban surge of the 1990s was both a reaction to the perceived failures of Democratic “blue” policies as well a reflection of the makeup of white-majority, middle-class neighborhoods in places like Brooklyn, Queens and the San Fernando Valley that featured healthy numbers of politically moderate “Reagan Democrats”—or Bill Clinton Democrats, circa 1992

Since then, these communities have been largely supplanted by groups far more likely to embrace a more progressive political stance: racial minorities, hipsters, and upper-class sophisticates. These groups have swelled, and gotten much richer, in places like brownstone Brooklyn or lakeside Chicago, while the number of inner city middle-class neighborhoods, as Brookings has demonstrated, have declined, to 23 percent of the central city—half the level in 1970.

This new urban configuration, notes the University of Chicago’s Terry Nichols Clark, tend to have different needs, and values, than the traditional middle class. Since their denizens are heavily single and childless, the poor state of city schools does not hold priority over the political power of the teachers unions. The key needs for the new population, Clark suggests, are good restaurants, shops and festivals, not child-friendly parks and family-oriented stores. Sometimes even crazy notions—such as allowing people to walk through the streets of San Francisco naked—are tolerated in a way no child-centric suburb would allow.

These tendencies underscore as well the increasingly homogeneous political culture emerging in cities. In 1984, for example, Ronald Reagan took 31 percent of the vote in San Francisco, and 37 percent in New York. He actually carried Los Angeles. By 2012, a Republican with a more moderate history could not muster 20 percent of the vote in San Francisco. And Mitt Romney lost Los Angeles by more than a 2-1 margin, while garnering barely 20 percent in all New York boroughs besides Staten Island.

Economic Hubris

These changes also reflect a shift in the economic role of cities. Until the 1970s, cities were centers of production, distribution and administration. Then the industrial base of urban areas, and related jobs such as logistics, began moving away from the traditional manufacturing cities to overseas, the suburbs or the Southeast. In 1950 New York, according to economic historian Fernand Braudel, 1 million people worked in factories, mostly for small companies. Today the city’s industrial workforce now stands at a paltry 73,000, a dramatic decline from some 400,000 as recently as the early 1980s.

A similar, if less spectacular, decline has taken place in what are still the two largest industrial metropolitan statistical areas, Chicago and Los Angeles. The one-time “City of Big Shoulders” and its environs had 461,600 industrial jobs in 2009. Today it has fewer than 300,000. Los Angeles, in a process that started with the end of the Cold War, has seen its once-diverse industrial base erode rapidly, from 900,000 just a decade ago to 364,000 today.

In some cities, a new economy has emerged, one that is largely transactional and oriented to media. The upshot is that denizens of the various social media, fashion and big data firms have little appreciation of the difficulties faced by those who build their products, create their energy and food. Unlike the factory or port economies of the past, the new “creative” economy has little meaningful interaction with the working class, even as it claims to speak for that group.

This urban economy has created many of the most unequal places in the country. At the top are the rich and super-affluent who have rediscovered the blessings of urbanity, followed by a large cadre of young and middle-aged professionals, many of them childless. Often ignored, except after sensationalized police shootings, is a vast impoverished class that has become ever-more concentrated in particular neighborhoods. During the first decade of the current millennium, neighborhoods with entrenchedurban poverty actually grew, increasing in numbers from 1,100 to 3,100. In population, they grew from 2 million to 4 million.Some 80 percent of all population growth in American cities, since 2000, notes demographer Wendell Cox, came from these poorer people, many of them recent immigrants.

Such social imbalances are not, as is the favored term among the trendy, sustainable. We appear to be creating the conditions for a new wave of violent crime on a scale not seen since the early 1990s. Along with poverty, public disorderliness, gang activity, homelessness and homicides are on the rise in manyAmerican core cities, including Baltimore, Milwaukee, Los Angeles and New York. Racial tensions, particularly with the police, have worsened. So even as left-leaning politicians try to rein in police, recent IRS data in Chicago reveals, the middle class appears to once again be leaving for suburban and other locales.

Urbanity and Politics

These social and economic changes inform the new politics of the Democratic Party. On social policy, the strong pro-gay marriage and abortion positions of the Democrats makes sense as cities have the largest percentages of both homosexuals and single, childless women. When the party had to worry about rural voters in South Dakota or West Virginia, this shift would have been more nuanced, and less rapid.

Yet with those battles essentially won, the new urban politics are entering into greater conflict with the suburban mainstream, which tends to be socially moderate, and even more so with the resource-dependent economies of rural America. The environmental radicalism that has its roots in places like San Francisco and Seattle now directly seeks to destroy whole parts of middle America’s energy economy.

Such policies tend to radically raise energy costs. In California, the green energy regime has already driven roughly 1 million people, many of them Latinos in the state’s agricultural interior, into “energy poverty”—a status in which electricity costs one-tenth of their income. Not surprisingly, those leaving California, notes Trulia, increasingly are working class; their annual incomes in the range of $20,000 to $80,000 are simply not enough to make ends meet.

Geography seems increasingly to determine politics. Ideas on climate policy that seem wonderfully enlightened in Manhattan or San Francisco—places far removed from the dirty realities of production—can provide a crushing blow to someone working in the Gulf Coast petro-chemical sector or in the Michigan communities dependent on auto manufacturing.

It’s more than suburban or rural jobs that are on the urban designer chopping block. Density obsessed planners have adopted rules, already well advanced in my adopted home state of California, to essentially curb much detested suburban sprawl and lure people back to the dense inner cities. The Obama administration is sympathetic to this agenda, and has adopted its own strategies to promote “back to the city” policies in the rest of the country as well.

But as these cities go green for the rich and impressionable, they must find ways to subsidize the growing low-paid service class—gardeners, nannies, dog walkers, restaurant servers—that they depend on daily. This makes many wealthy cities, such as Seattle or San Francisco, hotbeds for such policies as a $15-an-hour minimum wage, as well as increased subsidies for housing and health care. In San Francisco, sadly, where the median price house (usually a smallish apartment) approaches $1 million, a higher minimum wage won’t purchase a decent standard of living. In far more diverse and poorer Los Angeles, nearly half of all workers would be covered -- with unforeseen impacts on many industries, including the largegarment industry.

These radicalizing trends are likely to be seen as a threat to Democratic prospects next year, but instead will meet with broad acclaim among city-dominated progressive media. Then again, the columnists, reporters and academics who embrace the new urban politics have little sympathy or interest in preserving middle-class suburbs, much less vital small towns. If the Republicans possess the intelligence—always an open question—to realize that their opponents are actively trying to undermine how most Americans prefer to live, they might find an opportunity far greater than many suspect.

This piece first appeared at Real Clear Politics.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo by Kevin Case from Bronx, NY, USA (Bill de Blasio) [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

A $15 minimum wage will make

A $15 minimum wage will make many low-skilled people unemployable. Maybe the idea is to get them out of the cities or the states? I don't know but if you want to raise their take-home above the market rate an expanded and improved earned-income tax credit is the way to go. It is dumb to think you can make employers fix the problem by simply mandating higher wages. Econ 101

Why are we so poorly led?