I recently made a couple of tweets/Facebook posts pointing out that market declines threaten California’s budget surplus. I referenced articles in the WSJ and Bloomberg, and I thought the observation was non-controversial—almost banal.

So I was surprised at the feedback. One person asked why. Another said it doesn’t mean anything until holders of declining assets cash out. Yet another pointed out that the wealthy were back to where they were eight months ago. Finally, one said we wouldn’t know of the impact until after the end of the next budget year.

Let’s answer the question "Why?" first: A decline in asset prices would have a detrimental impact on California’s budget because California’s tax system is extraordinarily progressive, with the result that a few really wealthy people pay a huge proportion of California’s taxes. California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office has estimated that the top one percent of California’s population paid half of the state’s income taxes in 2012. Income taxes are California’s major revenue source, comprising about 65 percent of the state’s income.

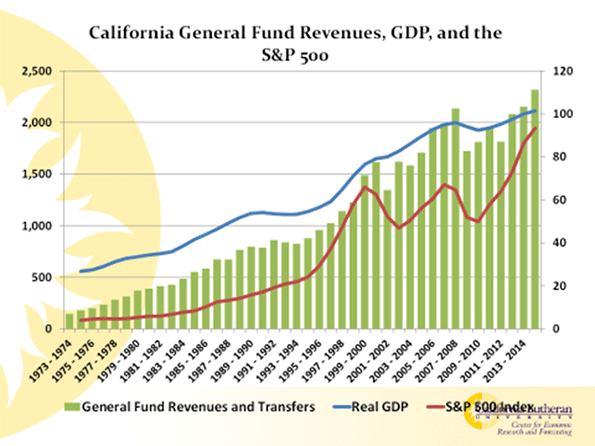

Since much of wealthy people’s income is from increased asset values—capital gains—rather than from wages that have been paid to them, their income, and thus California’s tax revenue, is more volatile than the economy. California revenue tracks changes in asset values more closely than it tracks changes in economic growth. See the following chart:

The increased revenues from the dot-com boom, the 2000s asset boom, and today’s boom are readily apparent in the chart. The declines that inevitably follow booms are also apparent.

California goes through these repeating cycles like a bad dream. Asset prices increase. California’s revenues increase. Sacramento spends that windfall as if asset prices will continue to rise forever. Worse, legislators commit to future spending as if the boom will continue forever.

Of course, booms don’t go on forever. Inevitably, prices fall. The gains that drive California’s revenue turn into losses, and California faces yet another budget crisis. Sacramento responds by raising taxes on the wealthy, and increasing the state’s reliance on the few wealthy. This pretty much guarantees that the problem will be even worse in the next cycle.

It’s a self-reinforcing boom and bust cycle of ever increasing revenue volatility.

It’s amazing to me that California’s leadership continues to do this, and that Californians allow it. It can only be possible because so few Californians understand the state’s finances. The people who responded to me are relatively well informed; far better informed than most Californians. Yet, even they don’t know how California’s revenues work.

It appears that California’s susceptibility to asset volatility is California’s best kept secret. That needs to change.

Governor Brown was hailed as a hero when proposition 30 was passed, raising taxes on those who earn over $250,000 a year. It was even retroactive. California’s revenues soared, a result of the combination of new taxes and a huge bull market on Wall Street. It was said that Brown had solved California’s deficit problem. What he really did was sow the seeds of California’s next budget crisis.

What about the next response I heard, the objection that losses have to be realized before they impact California’s budget? Can we be realistic? The people who pay over half of California’s income taxes have resources that are unimaginable to most of us. You can bet your net worth that, for tax purposes, they recognize losses as quickly as possible and do their best to never realize gains. The gains we’ve seen were only reluctantly recognized. The losses will be enthusiastically recognized.

The comment about retained wealth—that the wealthy were back to where they were eight months ago—is a red herring. Wealth is irrelevant. Income taxes are paid on changes to wealth, not wealth. And, we don’t have to wait until after the fact, or until the end of the fiscal year, to know what the story will be. We don’t even need a real bust to see California’s surplus slip away. The surplus is dependent on increasing asset values. It's not necessary for asset prices to decline for the surplus to be eliminated. All that is required is that asset values cease increasing.

I thought it was irresponsible for people to cheer California’s surplus without at least recognizing its fragility. Ignoring the fragility now, when asset prices are especially volatile, is foolhardy. Our governor and legislators know what will become of California’s surplus when asset prices decline. They should be developing a plan.

Of course, California’s leadership is not working on a plan. Instead, the best of them (admittedly a low hurdle) continue to pat themselves on the back and hope for the best. Some do worse by attempting to increase California’s spending even more.

Besides developing a plan to deal with the sure-to-come deficit, Sacramento should be working on a plan to make California’s revenues more closely track broad economic activity, instead of volatile asset prices. This would require a broader tax base and a less progressive income tax. Unfortunately, that’s not likely to happen.

Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org.

Flickr photo by Thomas Hawk: The Good Life; the Ritz Carlton, Laguna Niguel, California.