Over the last half-century, more restrictive urban planning policies have been associated with undermined housing affordability for the middle class. Given the primacy of housing costs in household budgets, this also means that these restrictive policies, especially urban containment, have been associated with greater overall poverty. Some research even suggests that rigid regulation has taken a heavy toll on the economy.1

Unfortunately, much of the present housing affordability discussion profoundly misses what is probably the biggest issue — metropolitan area (market) restrictions on urban fringe development (the theological term is “urban sprawl.” Instead we here about smaller lot sizes (as if lot size matters much), parking (as if people will give up their cars and walk), historic preservation and a host of minutia that cannot hold a candle to the effect of blocking development in the one part of the market) that defines the land value base for the entire enclosed area — the urban fringe.

Fundamentally, urban containment seeks to stop the expansion. of urban areas (sprawl) and increase urban population densities. The international planning orthodoxy uses strategies such as greenbelts, urban growth boundaries, rural (large lot) zoning on urban peripheries, and compact city policies.

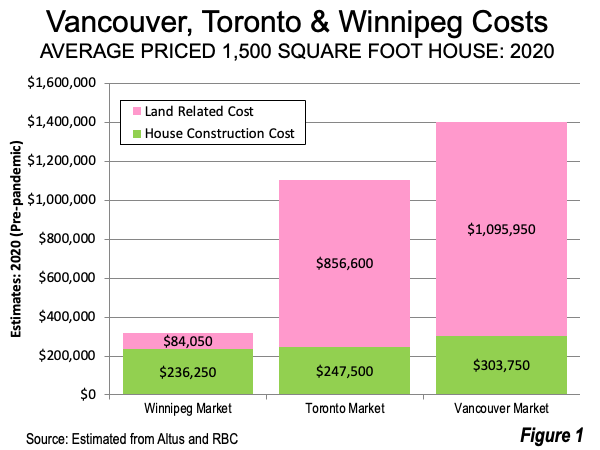

Generally, land values in the physical city (built-up urban area) increase toward the urban center and stronger commercial centers (all else equal).2 Urban containment disrupts this pattern, causing abrupt land value spikes at urban growth boundaries and greenbelts — as well as higher land prices throughout the encircled area, including the inner city. This drives up land prices, which tend to become the most expensive factor of production where there is urban containment (Figure 1), as is indicated in Vancouver and Toronto, compared to Winnipeg.

It’s rather like eggs. When there is a shortage of hens, the prices of eggs rise. When there is a shortage of land the price of housing rises, often at very high rates.

Much of this can be traced back to the British Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, which established large greenbelts around urban areas, in which it was illegal to build houses, leading land and house cost escalation.

London School of Economics professor Christian Hilber told The Wall Street Journal: “What is striking is that the countries at the top [of home-price growth] are all Commonwealth countries that copied elements of the restrictive British planning system.” This is evident not only London, but also Vancouver, Toronto, Auckland, and all of Australia’s major markets. This also extends to many markets throughout the world where similar policies have produced similar consequences (Portland, Seattle, Denver, Miami and virtually all of California and a number of European markets).

Each of these strategies reduces the land available for development of middle-income housing in the forms most households prefer (ground-oriented, such as detached, semi-detached, or row houses).

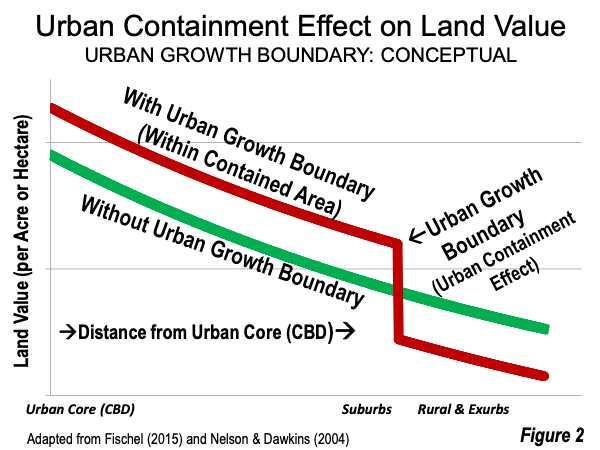

The impact of urban containment on land values is illustrated in Figure 2. The land value increases within the urban growth boundary (UGB) are the “urban containment effect.” These regulations make it all but impossible to profitably build tracts of housing affordable to middle-income households in many markets.

According to prominent urban planners Arthur C. Nelson and Casey J. Dawkins: “Urban containment programs can be distinguished from traditional approaches to land-use regulation by the presence of policies that are explicitly designed to limit the development of land outside a defined urban area while encouraging infill development and redevelopment inside the urban area.”

They also emphasize that: “If a gap in land values on both sides of the boundary does not emerge, either the boundary is too large in the near term or there is too much development potential remaining in rural areas regardless of any land-use restrictions.”

Regrettably, proponents of the international planning orthodoxy were right—urban containment is associated with materially higher land prices. The planning retort is that people can live at higher densities, such as in high rise apartments or condos. The problem is that’s not how most households prefer to live and many consider this a lower standard of living. Households are leaving the most expensive areas not only because of the high price to income ratios, but also because of an association (perceived or real) between higher crime rates and higher densities, not to mention pathetic education performance.

The preference for lower densities is illustrated by the much lower urban densities in major metropolitan counties attracting net domestic migrants between 2020 and 2023 (2,150 per square mile), compared to the much higher urban densities of major metropolitan counties losing domestic migrations (11,500 per square mile)

More than five decades ago, legendary planner Sir Peter Hall (London School of Economics) concluded that “perhaps the biggest single failure” of British urban containment had been its failure to prevent losses in housing affordability.3 Notably, this was before the comprehensive urban containment policies were adopted in Portland and many other markets in Canada, Australia, the United States and elsewhere.

This is consistent with economic principle. Former principal urban planner at the World Bank, asserts that Alain Bertaud: “arbitrary limits on city expansion” (such as urban growth boundaries and greenbelts) result in “predictably higher prices.”

Worse off due to planning? Ultimately, the purpose of urban planning should be about people. Fabled urbanist Jane Jacobs offered the test: “If planning helps people, they ought to be better off as a result, not worse off.” Paul Cheshire, Max Nathan, and Henry Overman of the London School of Economics put said “The ultimate objective of urban policy is to improve outcomes for people rather than places; for individuals and families rather than buildings.”

In recent years, the densification agenda of urban planning has become more evident. The solution, say some planners is (to repeat The New York Times headline) “Build Build Build Build Build Build Build Build Build Build Build Build Build Build.” No matter how many “builds” in a headline,” it does nothing to reform the regulations in Portland, Seattle, California and elsewhere where houses that are affordable cannot be legally built where it matters. Moreover, in many markets land prices have been driven up so much that houses cannot be profitably built at prices affordable to middle-income households

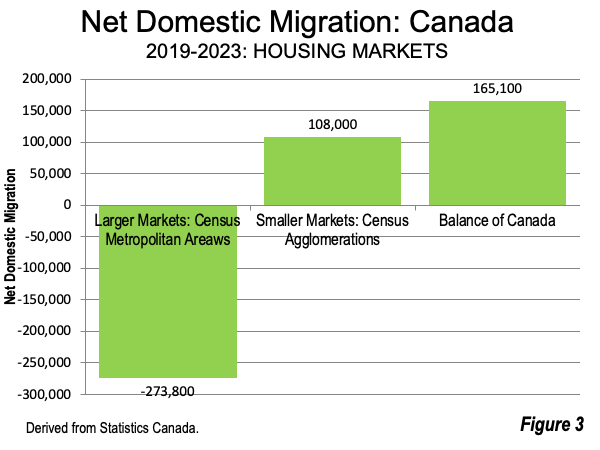

Meanwhile, households are taking housing affordability policy into their own hands, by leaving the dysfunctional urban containment markets and heading to where housing and the standard of living is more affordable.

In Canada, between 2019 and 2023, large markets (Census Metropolitan Areas) experienced a net loss of nearly 275,000 domestic migrants. Smaller markets (Census Agglomerations) gained nearly 110,000, while the rest of the country gained 165,000 (Figure 3). This contrasts sharply with 2004–2018, when large markets gained 19,000 and smaller markets 77,000, while the balance of the nation gained 97,000.4

In the United States, since 2010, large metropolitan areas have experienced increasing out-migration. Between 2020 and 2023, all metro areas over 1 million people lost net domestic migrants, while all classifications below 1 million gained them (Figure 4).

The bottom line is that without material reforms to urban containment regulations, such that the competitive market for land is restored, any serious improvement in housing affordability is unlikely. The housing markets of California and Australia, as well as Vancouver, Toronto, Portland, Seattle and so on and so on seem likely to deteriorate, and certainly not to materially improve.

Addendum: As this article was in production, The New York Times published an article by well-known housing reporter Conor Dougherty suggesting the need for more “sprawl” to solve the US housing crisis. Long friendly to density advocates, he has now admitted that densification alone would not solve the problem. He is right.

1. For example, see: Hsieh, Chang-Tai and Moretti, Enrico, Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation (May 2018). CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP12912.

2. William Alonso (1964), Location and Land Use: Toward a General Theory of Land Rent (Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press).

3. Peter Hall, et al (1973), The Containment of Urban England, Volume 2.

4. See: Financial Post.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy firm located in the St. Louis metropolitan area. He is a Senior Fellow with Unleash Prosperity in Washington and the Frontier Centre for Public Policy in Winnipeg and a member of the Advisory Board of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University in Orange, California. He has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris. His principal interests are economics, poverty alleviation, demographics, urban policy and transport. He is author of the annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey and author of Demographia World Urban Areas.

Photo: Vancouver, BC (by author).