The last article outlined research on job access by cars, transit and walking by the University of Minnesota Accessibility Observatory that assesses mobility by car, transit and walking in 49 of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas. Of course, it is to be expected that the metropolitan areas will have the largest number of jobs accessible to the average employee simply by virtue of their larger labor markets.

Indeed, smaller, but important major labor markets, from Grand Rapids and Buffalo to Philadelphia and Washington seem unlikely to ever rival the job numbers in metropolitan areas like New York and Los Angeles.

Researchers such as Remy Prud’homme and Chang-Woon Lee of the University of Paris, David Hartgen and M. Gregory Fields of the University of North Carolina, Charlotte have shown that a city (metropolitan area( is likely to experience better economic results if its transportation system provides better mobility. This includes greater job creation, greater economic growth and poverty reduction.

Virtually any metropolitan area will do well to focus on maximizing mobility. This article describes the percentage of jobs in each of the 49 metropolitan areas that can be reached by the average employee in 30 minutes, a time slightly longer than the US one-way work trip average travel time of 26.4 minutes.

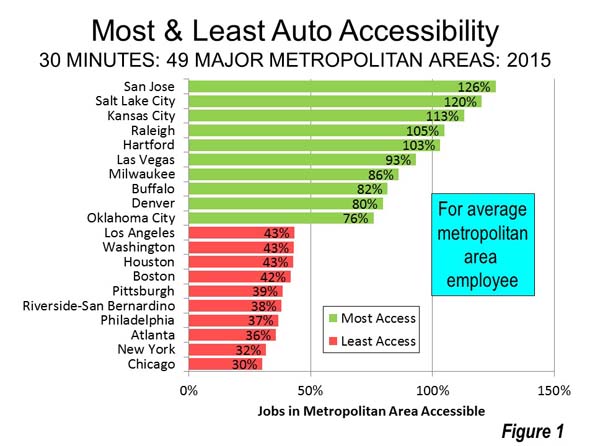

Accessibility by Auto

The leading metropolitan area in auto accessibility include is San Jose . Despite its reputation as an ultra-green area, 90 percent of San Jose commuters who do not work at home use cars to get to work. San Jose does warrant accolades for its 4.7 percent work at home share, the most environmentally friendly mode of work access. Transit has a 4.1 percent share. More than 100 percent of the metropolitan area’s jobs can be reached in 30 minutes, largely because the San Francisco metropolitan area is virtually across the street, providing additional employment opportunities.

The balance of the top 10 is smaller, metropolitan areas, Salt Lake City, Kansas City, Raleigh and Hartford, where the average employee can reach jobs equaling more than 100 percent of the metropolitan total in 30 minutes. The second five include Las Vegas, Milwaukee, Buffalo, Denver and Oklahoma City. All but three of the 10 cities with best access has urban densities that are lower than the major metropolitan average.

The least automobile accessibility is in larger metropolitan areas, where there is generally much greater traffic congestion. New York and Chicago have the lowest levels of 30 minute accessibility, followed by Atlanta, higher than would be expected, in large measure because of its sub-standard arterial street system, which in other cities provides effective alternatives to freeways (Figure 1).

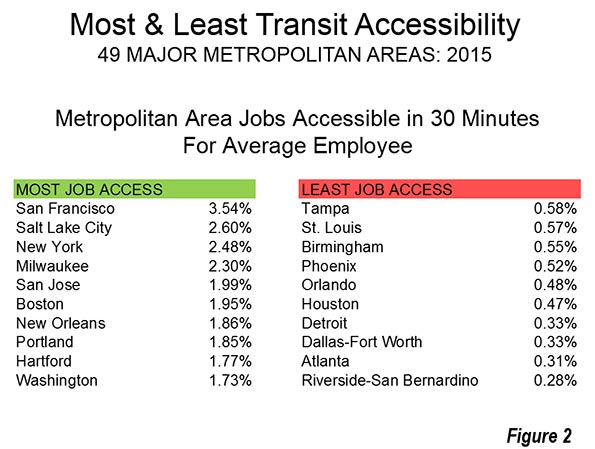

Transit

Employees can reach the greatest share of metropolitan area jobs by transit in San Francisco (3.54 percent), Salt Lake City (2.60 percent), New York (2.48 percent), Milwaukee (2.30 percent) and San Jose (1.99 percent). The second five includes three cities with strong legacies of transit such as Boston, Portland and Washington, along with New Orleans and Hartford.

The least transit access is in Orlando, Houston, Detroit, Dallas-Fort Worth, Atlanta and Riverside-San Bernardino, all below 0.50 percent (Figure 2).

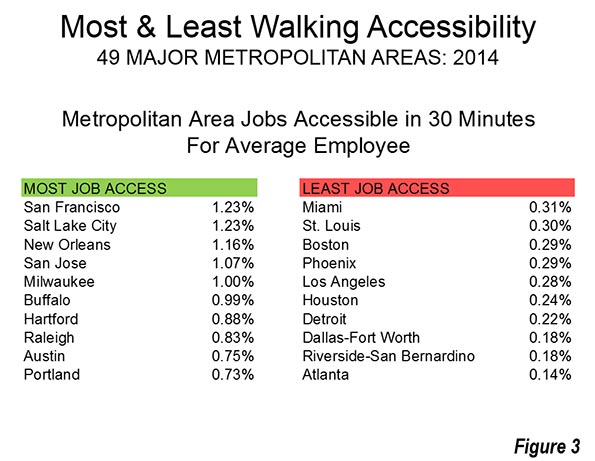

Walking

Walking can get the average employee to the greatest share of metropolitan jobs in 30 minutes in San Francisco (1.23 percent), Salt Lake City (1.23 percent), New Orleans (1.16 percent), San Jose (1.07 percent) and Milwaukee (1.00 percent).

Among the 10 cities with the least walking access, none reaches one-third of one-percent. These include one Northeastern city, Boston, St. Louis and Detroit in the Midwest and an expected array of western and southern cities, such as Los Angeles, Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Phoenix, Riverside-San Bernardino, Miami and ,in last place, Atlanta (Figure 3).

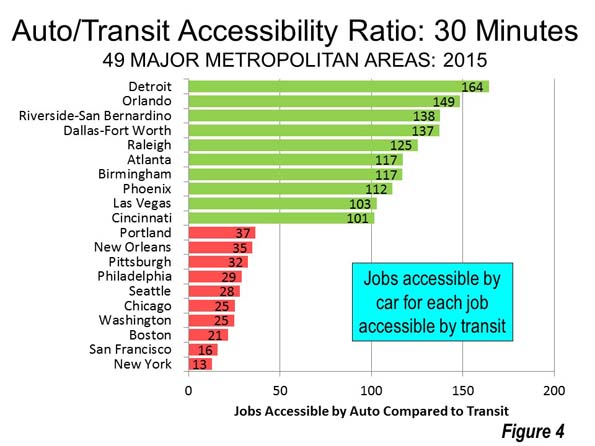

The Automobile Access Advantage

The data indicates that automobiles have far superior access to employment in every major metropolitan area. The cities that have the smallest automobile advantage are generally credited with having the best transit systems. But there is relatively little practical opportunity for commuting by transit to metropolitan jobs. In the worst case, the average New York auto commuter can reach 13 times as many jobs as by transit in 30 minutes, 16 times in San Francisco, 21 times in Boston, 25 times in Chicago and Washington. In Seattle, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, New Orleans and Portland the average employee can reach from 28 to 37 times as many jobs by car as by transit.

The auto advantage is much greater in other cities. In Detroit the average commuter can reach 164 times as many jobs by car is by transit, 149 times as many in Orlando, 138 times and Riverside San Bernardino, 137 times in Dallas-Fort Worth and 125 times in Raleigh. Atlanta, Birmingham, Phoenix, Las Vegas and Cincinnati commuters can reach more than 100 times as many jobs by car in 30 minutes as by transit (Figure 4).

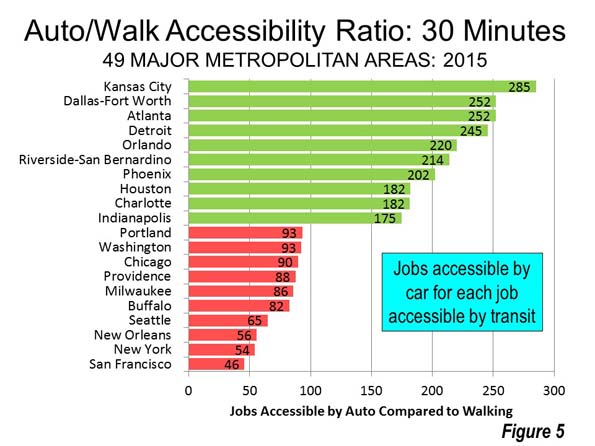

Not surprisingly, the disparities are even greater between autos and walking. Walking does best compared to cars in San Francisco, where auto commuters can reach 46 times as many jobs by car as by walking. The least advantaged pedestrians are in Kansas City, where the average automobile commuter can reach 285 times as many jobs by car as by walking (Figure 5).

New York in Context

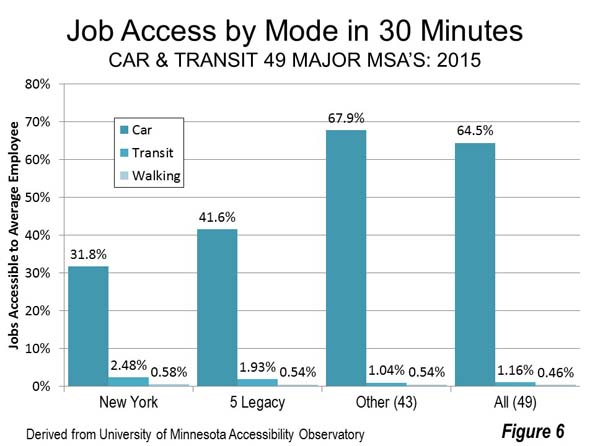

A colleague pointed out that the domination of transit statistics by New York would justify looking at how the nation’s largest metropolitan area compares to others. New York commuter access in 30 minutes of 2.48 percent of jobs by transit is about 1/5 higher than the 1.93 percent in the other five metropolitan areas with transit legacy core cities. New York’s commuters can reach nearly 2.5 times the percentage of metropolitan jobs accessible within 30 minutes as in the other 43 metropolitan areas (Figure 6). Transit is a lot more comprehensive in the New York metropolitan area, but cannot compete with automobile access by a long shot.

Improving Mobility and the Economy

For decades there has been an assumption that transit is an alternative to the automobile throughout the metropolitan area. The University of Minnesota Accessibility Observatory shows any such conception to be at best an exaggeration. Indeed, transit and walking provide only a small fraction of the access available by automobile. This is not likely to change at any practical level of public funding. As Professor Jean-Claude Ziv and I estimated that it could take all of an urban area’s gross domestic product each year just to provide the point to point access available by cars.

There are places that transit is competitive with the automobile, notably the nation’s largest downtown areas (central business districts or CBDs), which are in the six transit legacy cities. However, travel times are far slower than the national average, due to higher levels of traffic congestion and greater reliance on transit, which tends to be slower than cars overall. For example, commuters to Manhattan---by far the nation’s largest CBD --- have transit travel times of 52 minutes, while the travel time by car is 51 minutes, according to the American Community Survey. Either way, the average one-way travel time is about twice the national average. However, even in New York, there are far more jobs outside the CBD, traffic congestion is far less and the speedier access by car makes transit generally uncompetitive to these dispersed locations.

In the past, it was not unreasonable to believe that transit could materially improve mobility in metropolitan areas. The new research undermines any such conception. Maximizing metropolitan mobility --- minimizing work trip travel times --- is an important strategy for jump-starting the economy, creating jobs and restoring economic growth to historic levels. Urban transportations strategies need to be selected based upon the outcome of superior access, without regard to mode.

Photograph: Interstate 10, Houston by Socrate76 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.