As a displaced Detroit Tigers fan who adopted the Chicago White Sox as my team, I often wonder how our city's other team, the Cubs, became an integral institution in the remaking of our city, while the White Sox have not. I published a piece at my Forbes site some time ago that detailed my thoughts on how the Cubs facilitated that transition. The Cubs' growth in prominence, particularly from 1969 until today, parallels the city's transition from Rust Belt to Global City. Conversely, the White Sox have diminished in prominence over the same span. I realized the Sox missed out on the locational advantages the Cubs enjoyed, and circumstances and mistakes have hurt them.

Once again, readers may ask, "what does any of this have to do with cities?", so let me explain. Baseball, I believe, holds a special place as a sport that is an institution and amenity for the places they call home. As the nation's oldest professional team sport, it has an enduring history in many of our largest cities. In its early years, major league teams sought to establish close relationships with the neighborhoods that surrounded them; with 77 (and now 81) home games scheduled each year, that was just a good business practice. Teams in other sports have tried to replicate the institution/amenity feel, with varying degrees of success. Basketball and hockey are winter sports and played indoors. Football plays to much larger crowds and with far fewer games, and is far more likely to be viewed as a neighborhood intrusion than an amenity. But baseball is summer. It's (mostly) outdoors. It can be easily integrated into a neighborhood fabric. So, yes, I see baseball teams, baseball stadiums, as having an outsized impact on city revitalization that other sports teams can't compete with.

What I tried to capture in my Forbes piece is that before the Cubs enjoyed their current baseball success, they have for some decades enjoyed that locational success, and parlayed that into a successful partnership with the surrounding neighborhood. From that piece:

"Starting in 1969, the Cub mythology begins to grow, and television becomes a bigger part of it. Chicago kids would come home from school to watch day baseball games. Plays by David Mamet were being written about bleacher bums. At the same time, the economies of north and south were continuing to diverge. Institutions like DePaul and Loyola University, Children’s Hospital, and others, were attracting more of the Midwest’s best and brightest to study and work. And the Cubs became a very attractive amenity to people returning to cities exactly for that reason.

It was in the 1980s that the real and enduring changes occurred. WGN became a cable television superstation, and now Cub games were broadcast nationally. Throughout the ’80s, especially with Harry Caray at the helm in the broadcast booth, every game was a celebration of what Chicago, and specifically North Side Chicago, had to offer. A jewel of a ballpark, day baseball, views of sailboats on Lake Michigan and a dramatic skyline nearby — all of this became not just a Midwestern phenomenon, but a national one. Suddenly, it wasn’t just Midwestern kids who dreamed of moving to big city Chicago. It became national."

In other words, the heart of Cubbie fandom lies in its place: the old ballpark, the surrounding neighborhood, the bars and restaurants, the nearby lakefront, even the nearby eds and meds institutions that employ many of the neighborhood's residents -- they all blend together to create a unique and enviable environment.

Conversely, over the last 50 years or so the White Sox lost whatever locational advantage they had. Deeply identified as the "South Side's Team", their fortunes diminished just as the South Side's:

Meanwhile, as the Cubs became more popular in the late ’60s, the luster on the White Sox began to dim. The Bridgeport neighborhood that is home to the Sox is in many respects the polar opposite of the Cubs’ Lake View neighborhood. It’s working-class, with far fewer eds and meds institutions, and a Bronzeville neighborhood — also known as the Black Belt — that stood between it and the south lakefront. While Cubs fans sitting in the upper reaches could see sailboats on the lake, Sox fans could see a never-ending row of public housing towers.

Beginning in the late ’60s and early ’70s the fortunes of the Cubs and White Sox diverged as dramatically as their respective parts of the city.

First, Some Facts

Let's try to establish a context for the Cubs and White Sox by using the most accepted measure of popularity in baseball, attendance. Since 2001 the Cubs have been in the top tier of MLB attendance, with an average annual rank of eighth out of thirty teams. The Cubs are regularly in the mix with the Yankees, Dodgers, Cardinals, Giants, Mets, Red Sox and Angels as a top MLB draw. Over this period the Cubs have averaged just under 3 million fans per season, or about 37,000 per game. Cubs attendance has proven to be remarkably consistent and impervious to big fluctuations in wins and losses. The Cubs paid a big price in 2013 when attendance dropped by 11.8% after disappointing seasons in 2011 and 2012, but overall the Cubs increased attendance at a rate of 1.2% a year over the last sixteen seasons. MLB attendance has grown at a rate of about 0.6% annually since 2001.

The White Sox, however, are quite a different story. Since 2001 the Sox have consistently ranked in the bottom third in MLB attendance. They've averaged just over 2 million fans annually, or nearly 26,000 per game. That's enough to rank them 21st out of thirty teams in that span.

I haven't been able to document this yet, but I suspect the Sox may be among the more win-sensitive teams in MLB. Attendance jumped 21.3% from 2004 to 2005, the year the Sox won the World Series, and jumped another 26.2% in 2006, in the World Series afterglow. The Cubs have no such huge year-to-year gains over the last sixteen seasons. However, subsequent poor seasons meant attendance has dropped for eight consecutive seasons before ticking upward again in 2015. The Sox have gained about 0.5% annually in attendance since 2001, just under the MLB average.

Cubs fans, and Chicagoans in general, seem to accept the Cubs/Sox fandom differential as an immutable fact, but that's not the case. Historically speaking, as I wrote previously about this at Forbes, the White Sox regularly outdrew the Cubs following World War II and into the '60s. From the late '60s to early '80s, there was general attendance parity between the teams. Since the early '80s, the Cubs have regularly outdrawn the Sox. The Cubs have outpaced the Sox in attendance every year since 1992.

Downtown, Neighborhood and Suburban Teams

The Cubs are one of just a handful of major league baseball teams that have maintained a strong neighborhood identity and association. Out of 30 MLB teams, just nine are located in neighborhood locations today, with 18 located in downtown areas and three in the suburbs (including the Atlanta Braves, who moved to suburban Cobb County this season). Here are the nine so-called neighborhood teams, located at least two miles outside of the center of a city's CBD:

• New York Yankees

• Boston Red Sox

• Chicago White Sox

• New York Mets

• Philadelphia Phillies

• Washington Nationals

• Miami Marlins

• Oakland Athletics

• Chicago Cubs

Philadelphia, Washington, Oakland and Miami deserve special attention. By my eyes, the Phillies, Nationals and A's all play in stadiums that are beyond their cities' central business districts, but appear to be located in areas that are largely warehouse or former manufacturing districts, as opposed to residential or mixed-use areas. The home of the Miami Marlins opened in Miami's Little Havana in 2012, so one could argue it's had little time to develop -- yet -- a strong relationship with the surrounding neighborhood. (Kansas City -- the Royals' Kauffman Stadium, although within the city's limits, is so far from the city's downtown, and relies on interstate access to reach it, that it gets a "suburban" designation from me.)

The Yankees, Red Sox and Cubs are each intimately connected with their surrounding neighborhoods. Yankee Stadium is in the Bronx; while it doesn't seem to have the same revitalization impact on its surrounding area, it is within easy reach affluent Manhattan. The Red Sox' Fenway neighborhood and Fenway Park might be the closest analogue to the Cubs' Lake View/Wrigleyville neighborhood and Wrigley Field in terms of vibrancy and impact on the city. I'm less familiar with the connection between the Mets and the nearby Queens neighborhoods.

What Happened?

The White Sox, however, seem to have far less impact than the others on the surrounding neighborhoods. In fact, the White Sox' home seem most similar to the Oakland A's -- beyond downtown, and in the less-favored area of a two-team baseball market.

I don't know what happened with the A's and Oakland, but I think it's easy to figure out how the neighborhood fortunes, and subsequently the fan fortunes, of the Cubs and White Sox diverged. Keep in mind that prior to about 1950, the areas around Wrigley Field and Comiskey Park were more similar than they are today. But the area around Clark and Addison retained its neighborhood fabric, while the area around 35th and Shields mostly lost it. A few things factored into the divergence:

• Macro: the general decline of the South Side. A quick and easy way of seeing the difference between the North and South sides is looking at the median household incomes for the communities that house the respective teams, Lake View (Cubs) and Bridgeport (Sox). In 1970, the median household income in Lake View (in 2014 dollars) was $44,889. In Bridgeport, it was $48,548. In 2015, median household income in Lake View was $76,424, and in Bridgeport it was $42,951. This plays out more broadly as well; wealth has flowed into the north lakefront neighborhoods of the Near North Side, Lincoln Park, Lake View and Edgewater, and it flowed away from Bridgeport, Bronzeville, Washington Park and Woodlawn.

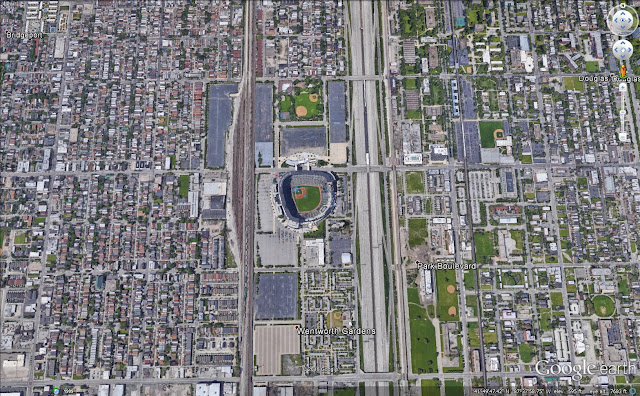

• Micro: Sox Park's hemmed-in geography. The home of the White Sox has long been hemmed in by two freight rail lines, about a third of a mile apart -- the Norfolk Southern line on the west and the Rock Island on the east. For much of its stretch on the South Side, the narrow corridor has been treated as a no-man's land with manufacturing uses, intermodal facilities, and poor quality housing strewn in. The intact Bridgeport neighborhood lies further west, and Bronzeville further east. A look at an aerial of U.S. Cellular Field highlights this:

• Lack of nearby institutions and amenities. Several key institutions are located near Wrigley Field -- DePaul and Loyola universities, several hospitals -- that make the area an attractive place to live. Near old Comiskey, the much smaller Illinois Institute of Technology and Mercy Hospital are still there, but their presence might not be felt in the same way in the community as those further north.

• Public housing construction. The year 1949 began a 20-year period where public housing was constructed just to the east of Comiskey Park. Dearborn Homes, Stateway Gardens, and Robert Taylor Homes were built within eyesight of Comiskey over that period, concentrating tens of thousands of low-income residents along the area's eastern edge.

• Dan Ryan Expressway construction. Between 1957 and 1962, the Dan Ryan Expressway was constructed just feet from Comiskey's eastern edge. Remember the narrow rail corridor? The 16-lane expressway, with a new public transit line in the median, made it even narrower.

When you combine these with some management differences between the Sox and Cubs, like the spotty radio and TV presence the Sox had when compared to their Cub brethren, and the failed venture to showcase Sox as a pay-per-view attraction on CableVision in the early '80s, and it becomes clearer how the two teams took vastly different tracks.

Paths to White Sox Success -- And Urban Revitalization

That being said, I think there are ways the White Sox could reclaim the kind of locational advantage they once had and the Cubs currently enjoy. However, it would mean the Sox would have to view themselves as a city institution invested in the revitalization of its surrounding area and employ unconventional tactics. Otherwise, they may need to consider other options. Here's what they can do:

• Stay at 35th and Shields -- and partner with commercial and residential developers. In the late '80s, when the White Sox threatened to leave Chicago and received the public gift of U.S. Cellular Field in return, a counter-proposal was floated by Chicago architect Philip Bess to create Armour Field. It was to be a stadium that wouldn't just be firmly integrated into the fabric of the surrounding community -- it would create community where none currently existed. Take a look:

The oddly-shaped outfield harkens back to the New York Giants' Polo Grounds, and Bess took pains to re-create the outlines of old Comiskey. More importantly, Bess frames the stadium with mixed-use development to the east, west and south of the stadium, and includes a circle at 35th and Wentworth that creates a signature entrance into the area. I'm guessing this type of development would bring the same types of residents who live near Wrigley today. I've never heard an explanation from the Sox for why this proposal was rejected, but I assume costs had much to do with it. And yes, working on the commercial and residential sides of the project would be a challenge.

This, of course, is just one redevelopment option. If the Sox are serious about staying at 35th and Shields, it would be in their best interest to lead the revitalization of the surrounding area.

• Find another neighborhood site on the South Side. There are likely other spots on the South Side that don't have the constraints that prevent Cubs-style community cohesiveness and neighborhood connection. One such site could've been the 49-acre site of the former Michael Reese Hospital on the Near South lakefront; it was formerly considered as the site for the Olympic Village in Chicago's 2016 Olympic bid, but is now being redeveloped as a major mixed-use development. I've also considered locations in largely manufacturing areas adjacent to the Southwest Side's Orange Line. I'm sure there are other possible sites out there. All, however, would probably come with some significant neighborhood resistance, and have the same cost challenges inherent in the above scenario.

• Find a downtown or near-downtown location. It's quite possible that in a two-team baseball market, only one team can be the "neighborhood" team. If so, the Cubs are it. The White Sox could find a site downtown or nearby (to be sure, very expensive) and begin to shed their South Side identity by becoming the team at the center of the metro area. Even though they're not in a two-team market, the Detroit Tigers invigorated their fan base by moving from antiquated Tiger Stadium to Comerica Park in 2000, leaving the city's Corktown neighborhood for a downtown locale. During the '90s the Tigers were among the lower rung teams in attendance, drawing 1.5 million annually. The Tigers vaulted into the middle tier with the new stadium (and some on-field success) in the 2000's, averaging 2.5 million a season. Of course, the last option would be to...

• Move to the suburbs. The White Sox flirted with suburban locations in the late '80s. However, suburban stadium locations are seen less often today, particularly for baseball stadiums (Atlanta Braves excepted). Perhaps it's because suburbs or suburban counties are less able to put together the public financing packages that team owners often demand (or extort?). If it were to happen, my guess is that the Sox would target relatively affluent south or southwest suburban communities like Orland Park or Bolingbrook, so that the team could easily attract fans from a broad spectrum of the metro area without completely compromising its South Side heritage. Honestly, I see this as highly unlikely, as the return-to-the-city movement is moving ahead in Chicago as much as anywhere.

I couldn't fathom a move to another city now, so I won't explore it as an option.

Bottom line, despite their on-field failures over the years, the Cubs have done a masterful job of taking advantage of locational opportunities presented to them. The White Sox have had a more difficult go of it for the last 60 years or so, but could turn it around with the right kind of thinking. Here's hoping the White Sox can become the kind of integral institution of South Side change that the Cubs have been up north.

This piece originally appeared on The Corner Side Yard.

Pete Saunders is a Detroit native who has worked as a public and private sector urban planner in the Chicago area for more than twenty years. He is also the author of "The Corner Side Yard," an urban planning blog that focuses on the redevelopment and revitalization of Rust Belt cities.

Top photo: U.S. Cellular Field, home of the White Sox. Source: sportingnews.com