New Zealand’s Minister of Housing and Urban Development

According to Politik (which calls itself “New Zealand’s most authoritative news and political analysis website”) “Twyford said the only way to deal with the affordability issue was to deal with the land price issue and that meant dealing with the artificial scarcity of land caused by the planning system and the availability of finance for infrastructure.” He added: “I’m interested in us fixing this totally dysfunctional urban land economy.”

The dysfunctional urban land economy is, to a large degree, the result of urban containment policy used in Auckland that virtually outlaws detached housing subdivisions on the urban fringe required to maintain affordability. Indeed, the vast expansion of the middle-class during the decades following World War II owed much to such housing developments, not only in New Zealand, but also Australia, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, much of Western Europe, Japan and other places as well.

A Question of Values

Twyford characterized action on the housing affordability crisis as a “question of values,” and said “This is for us, for Labour, for our coalition government, this is fundamentally a social justice issue.” He added: “If we don’t deal with affordability we will have completely wasted the opportunity that has been given to our generation.”

ANZ Bank Report Links High House Prices with Reduced Productivity Growth

Minister Twyford’s comments were followed a few weeks later by a report written by economists at ANZ Bank, suggesting that “the effects of unaffordable housing might be much more pervasive than generally appreciated.” The report, “Holding the Key” suggested that New Zealand’s severely unaffordable house prices undermined both national productivity and economic performance.

According to the report, “The most significant determinant of differences in per capita incomes between countries is their productivity performance – and productivity growth in New Zealand has been lacklustre in recent decades.” It continued by asserting that “The challenges of low productivity growth and housing unaffordability … are inextricably linked.”

In particular, “Holding the Key,” cites a decline in home-ownership, with New Zealand’s rate falling from 2001 55% in 2001 to 50% in 2013. ANZ notes important social costs: “High house prices and declining rates of home ownership are important from the perspective of fairness – but also for outcomes in society. Home ownership is associated with greater stability, better educational outcomes and income prospects (controlling for other factors), and more favourable living standards in retirement… they create an obstacle to entering the market, increasing the divide between those who own and those who do not.”

With the much higher housing costs, households have a lower standard of living. They have less discretionary income, which limits their purchases of goods and services and reduces employment. They must accept lower quality housing. And, in some cases they have to seek assistance from governments and forced to seek subsidized housing. The costs for governments and taxpayers rise: “…expensive housing creates a significant fiscal cost, with the Government providing support to those in need.”

The report concluded: “Indeed, we would emphasise more broadly that improving housing affordability is an important part of any solution to tackle our productivity problem.” The authors indicate that more land supply needs to be made available, “with a steady future pipeline in train” and improvements in construction capacity as well as improved construction capacity and productivity.

Strong Land-Use Regulation and Productivity Losses: Evidence from Elsewhere

The ANZ Bank report adds to the growing list of economic analyses that connect overly expensive housing with stronger land use regulation. For example:

Chang-Tai Hseih of the University of Illinois, Chicago and Enrico Moretti of the University of California, Berkeley traced a nearly 10% annual loss in U.S. national output by 2009 from the expansion of housing regulation from the mid-1960s.

Kyle Herkenhoff of the University of Minnesota, Edward Ohanian of U.C.L.A. and Lee Prescott of Arizona State University estimate that if California’s land use regulatory structure were returned to the more market oriented situation of 1980, it “would increase national output, productivity “by about 1.5%.”

Matthew Rognlie, now of Northwestern University, found that the widening inequality gap found by French economist Thomas Piketty was largely due to housing and suggested re-examining land-use regulation.

The Human Costs of Urban Containment: Auckland and Beyond

The effect of urban containment is obvious in Auckland, where just 25 years ago, the house price-to-income multiple was near an affordable 3.0. The 14th Annual Demograhia Housing Affordability Survey showed that Auckland’s price-to-income multiple (median multiple) had risen to 8.8.

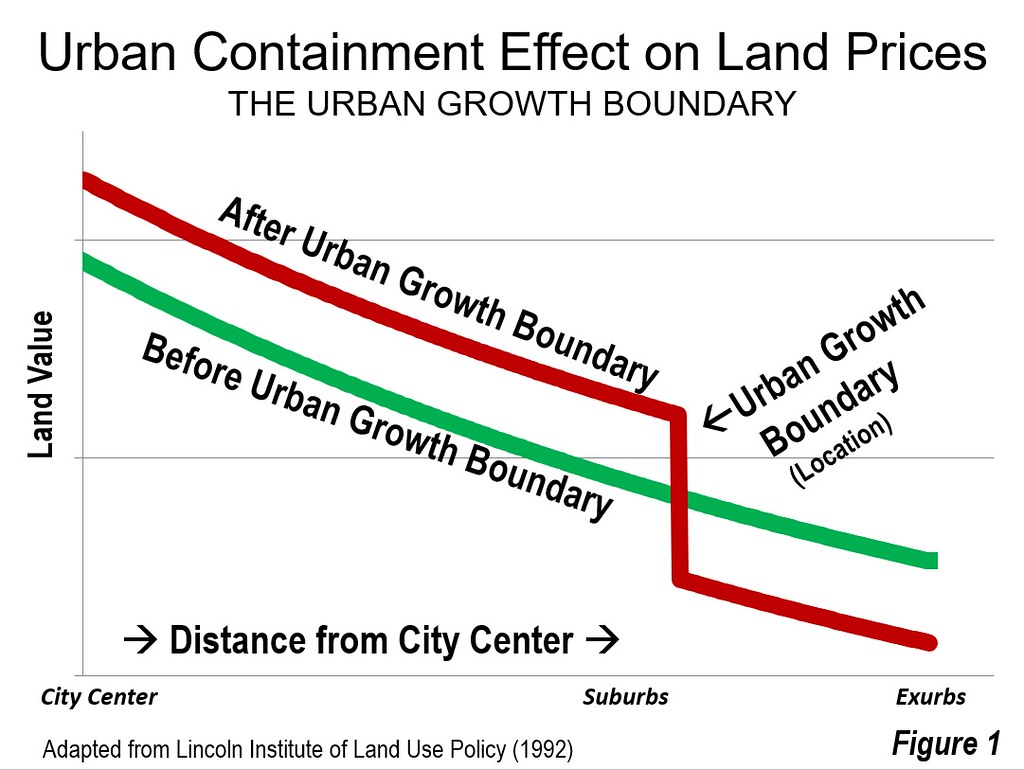

Early urban containment theories realized that urban growth boundaries were a risk to housing affordability (Figure). They offered a rosy theory that denser housing inside the UGB would keep house prices from rising.

It was a vain hope. Instead, much higher house prices have been typical where urban containment policy has been implemented. One of the most disastrous examples is “utterly unaffordable” Vancouver. With a UGB for more than four decades, Vancouver’s median multiple has skyrocketed to 12.6. This has occurred even as Vancouver has densified. Yet house prices have increased at four times the rate of inflation, for two decades or more. To say the least, Vancouver’s densification has not nullified the house price increases of urban containment.

Planning theory favors UGBs to stop endless urban expansion. Yet, UGBs are routinely associated with lower standards of living and greater poverty. In this regard, planning exhibits twisted priorities. As Paul C. Cheshire, Max and Nathan and Henry G. Overman of the London School of Economics asserted: “… that the ultimate objective of urban policy is to improve outcomes for people rather than places; for individuals and families rather than buildings.”

Moreover, UGBs are not even needed to control endless urban expansion, Toronto and Calgary showed until the mid-2000s that a higher-density compact urban form can be retained, while allowing suburban subdivision housing and preserving housing affordability. But both of these urban areas are now following the disastrous path of Vancouver. As expected, house prices have risen substantially relative to incomes. An urban growth boundary is like a “meat cleaver” that severs a very market dynamic necessary to keeping house prices low --- new houses on the urban fringe, affordable to the middle-class. Cities interested in fostering a strong middle-class need to avoid or repeal urban containment policy, from Auckland to the rest of the world.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: Auckland (by author)