Our way of life is a miracle for this kind of world, and … the danger lies in thinking that of it as ‘natural’ and likely to endure without a passionate determination on our part to preserve and defend it.” — W.V. Aughterson, The Australian Way of Life, 1951

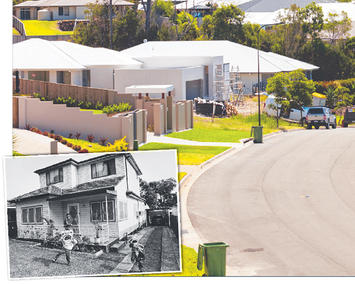

For generations, Australia has enjoyed among the highest living standards in the world. The “Australian dream”, embodied largely by owning a single-family home with a small backyard, included well over 70 per cent of households.

Today that dream is fading.

Those who are aged above 55, notes the Grattan Institute, still enjoy homeownership rates around 80 per cent but property ownership rates among 25-34-year-olds have dropped from more than 60 per cent in 1981 and to 45 per cent in 2016. Equally disturbing, new migrants, the lifeblood of an increasingly diverse country, have experienced a significant fall; skilled immigrants, for example, have seen their homeownership rate plunge just this decade from over 40 per cent to barely 25 per cent.

The obvious villain here is high-housing prices, that have risen twice as fast as incomes over the past four decades, a rate far higher than other high-income countries. Today, notes demographer Wendell Cox, "Sydney’s house prices, even after a recent readjustment, are higher, based on income, than any first world city besides Hong Kong; its housing costs eclipse great global cities like Los Angeles, New York, and London."

Needlessly Pricey

To an outsider, Australia’s high housing prices are puzzling for a big country with relatively few people. Only 0.3 per cent of the country’s land is already urbanised compared to 6 per cent in the UK and 3 per cent in the US. To be sure, much is desert, as is the case in America as well, but huge swathes near both east and west coasts remain largely uninhabited.

Most Australians should feel free to dream but instead must struggle against regulations designed to force densification and curb “sprawl”.

These policies, according to a recent Reserve Bank study, now adds 55 per cent to the price of a new Sydney home. As Australian cities once filled with family friendly neighbourhoods are being ordered to become denser, they will become far less congenial to families; according to projections from the Urban Taskforce, apartment will make up half of Sydney's dwellings mid-century, whereas only one quarter will be family-friendly detached homes.

This agenda is widely supported by the urban gentry, most academicians and the media. For the well-heeled and woke in places like Sydney’s harbourside, suburban development — critical to the “Australian way of life” — is seen as closer to purgatory than paradise. The fact most Australians live in suburbs, with more than four-fifths of families prefer living in single family homes seems to make little difference. To the usual aesthetic concerns of the new urbanists, climate change has added “saving the planet” to justify relentless densification.

Densification might bring more crowding, poverty, and a childless future but it’s OK as long as it serves the planet and wipes out the unaesthetic suburban form. “The suburbs are about boredom, and obviously some people like being bored and plain and predictable, I’m happy for them,” snarks Elizabeth Farrelly, urban and architecture critic for the Sydney Morning Herald. “Even if their suburbs are destroying the world.” But the actual linkage between emissions and the urban form is far less straightforward.

Suburban detached houses, according to one Australian study, use less energy per capita than those of inner-city urbanites. California, the hotbed of climate lunacy and forced densification, has reduced its greenhouse gases between 2007 and 2016 at a rate 40th per capita among the 50 states. It has succeeded, however, in driving up energy and housing prices well above the rest of the country; the world capital of the elite tech economy also suffers the highest cost adjusted poverty rate in the nation.

Similar failures can be seen in Germany where much heralded “energiewende” (energy transition) have led to soaring energy costs but disappointing results in terms of emissions declines and rising energy poverty. Almost anything high-income countries like Australia or the US do would be almost infinitesimal in terms of impact, when virtually all the growth in emissions comes from developing countries, led by China.

In reality, we can work on climate goals without sacrificing the aspirations of all but a few. Climate issues would likely gain more support, if done in more proven and less impoverishing manner. This would include such things as employing nuclear power, using increasingly abundant natural gas rather than coal or ruinously expensive renewables, as well as encouraging home-based and dispersed work.

How to Fight Back

Voters in democratic countries still have the power to challenge policies that undercut their aspirations. We do not have to consign our children to an emerging neo-feudal system where people remain renters for life, enjoying their video games or houseplants while profits from housing accrue mainly to the owner class who would become the modern versions of a medieval landlord.

This should not be an ideological issue. In the US, progressive presidents from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Bill Clinton supported suburban expansion and expanded homeownership. In Australia Labor leaders such as John Curtin and Gough Whitlam supported an expansive urban footprint and single family, owner occupied housing.

This, sadly, is increasingly not the case among today’s progressives --- whether US Democrats, the Australian Labor Party or Canada’s Liberals. They instead increasingly seek to impose enlightened rule from above to enforce their climate and social goals, even if it means keeping the majority from achieving their middle-class aspirations.

Ultimately, such policies threaten the very foundation of democracy. From the Athenian golden age, the Roman Republic, the earliest days of the Dutch Republic to the experience of US, Canada and Australia, dispersed land ownership and a vibrant middle class has been critical to self-rule. As the great US historian Barrington Moore put it, "no bourgeois, no democracy."

The good news is that even those living in suburbs won’t easily be led to slaughter. Despite constant hectoring in the mainstream media, Americans still rank climate as only their 11th leading concern, behind not just healthcare and the economy but immigration, guns, women’s rights, the Supreme Court, taxes, income and trade. A recent Harris-Harvard poll found that three-fifths of Americans reject the basket of Green New Deal policies, including a third of Democrats and half of people under 25.

These sentiments are widely shared across the planet. A recent UN survey of 10 million people found climate change ranked 16th in concerns. Most people in the developing world, notes environmental economist Bjorn Lonborg, “care about their kids not dying from easily curable diseases, getting a decent education, not starving to death.”

A Global Rebellion

Increased attempts to target suburban lifestyles, notably by raising fuel prices, already has led to mass protests in many affluent countries, including France, and normally more placid places like Norway and the Netherlands. Even in Germany there’s a mounting opposition to that country’s green agenda, which has sent the country’s powerful industrial base reeling from the associated high energy costs.

Recent elections in Canada and Australia show the huge divide between society’s self-selected elites and the hoi polloi. In Canada, the Liberal government lost many seats, as well as the popular vote, in large part due to green policies; much the same occurred in Australia in the last election, where conservatives, despite growing concerns over climate issues, gained seats, particularly in energy-producing areas. Predictably the results in Australia led local celebrities and pundits to brand their fellow citizens as unremittingly “dumb.”

Ultimately, the battle to defend the “Australian way of life”, and that of people in democracies around the world, depends on resisting the arrogance of the gentry, the planning elite and their real estate allies. The struggle to preserve the aspirations of the middle class, and their children, could well emerge as the signature issue of our time.

This piece first appeared in the Daily Telegraph.

Joel Kotkin is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. He authored The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, published in 2016 by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He is executive director of NewGeography.com and lives in Orange County, CA. His next book, “The Coming Of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class,” will be out this spring.