Amazon Air is 2020’s transportation juggernaut, flying high above the many airlines struggling to keep aloft during the coronavirus epidemic. This wholly owned subsidiary of retailing giant Amazon is growing rapidly in response to another surge in online buying. Amazon Air’s expansion marks one of the most significant developments in the U.S. air-cargo business in years—and is giving a shot-in-the-arm to smaller airports oriented primarily towards freight shipments.

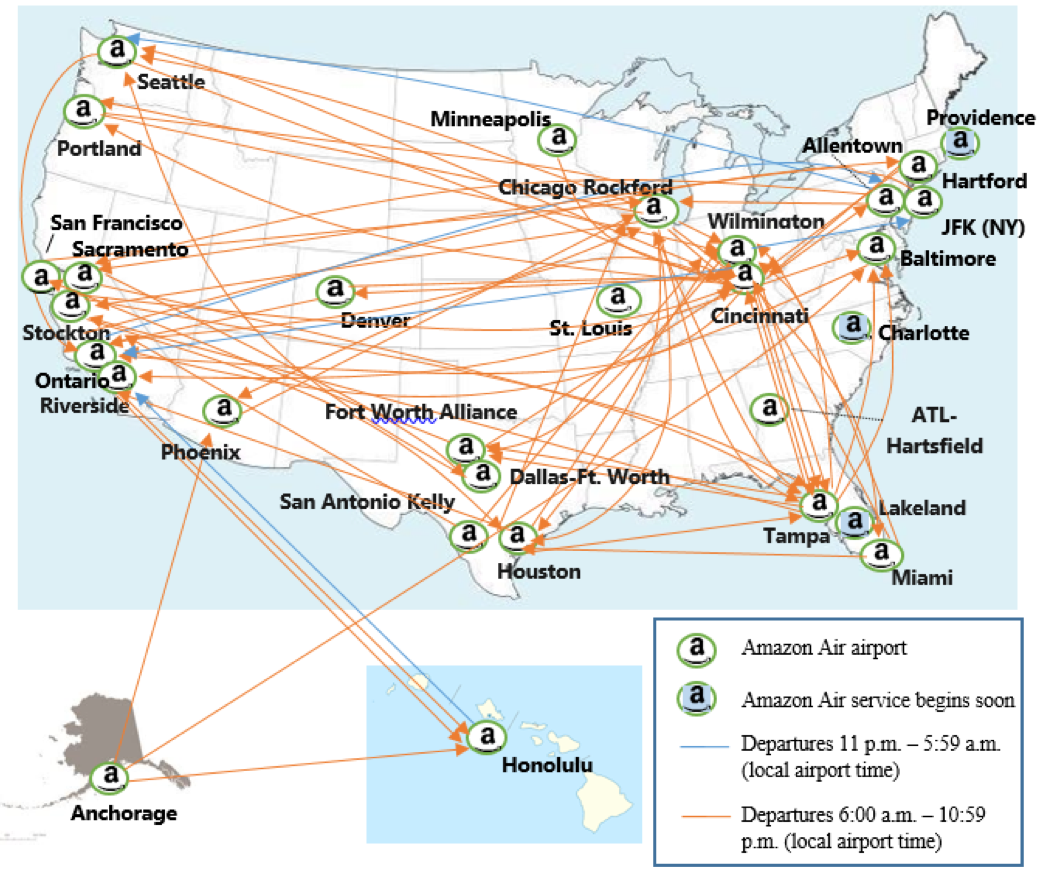

Having been flying since 2016, Amazon Air (formerly Amazon Prime Air) now has 45 planes and plans to grow to at least 70 by next year. Our new study on Amazon Air shows that it now operates almost 100 flights per day, despite being still primarily confined to the United States (Figure 1). It is operated entirely by contractors, primarily Atlas Air, Air Transport International, Southern Air, and Sun Country Airlines. A similar outsourcing strategy to that used to be operated by Amazon’s familiar delivery blue-colored vehicle. Because its contractors do not report Amazon-specific data to a federal agency, statistics about Amazon Air’s size and growth are elusive.

Our analysis, however, shows that Amazon Air has much of same DNA as DHL International, FedEx, and UPS, the country’s three largest air freight integrators (DHL primarily serves the international market). Like these massive vertically integrated companies, Amazon Air is designed to support door-to-door shipments. It’s building large distribution facilities at airports alongside these established stalwarts. Yet about three-quarter of flights, we found, depart between 6 a.m. and 11 p.m. (based on local time at airports), a virtual mirror image of the FedEx and UPS, which are largely nocturnal creatures. Its growth is being spurred by the expansion of Amazon Prime, which heavily promotes overnight and second-day delivery, and the COVID crisis has apparently pushed the carrier’s expansion into overdrive.

Amazon Air complements the retailer’s massive ground-based shipping network, which reportedly now surpasses 20,000 trucks. Its fleet is still only a fraction of the size of FedEx and UPS, and Amazon has shied away from jumbo-jets, preferring mid-sized planes such as the Boeing 767. But Amazon Air’s breakneck growth rate, its apparent rock-bottom costs, and its synergy with Amazon’s fulfilments centers, which now number more than 170 in the U.S. alone, no doubt have many air-cargo executives are biting their nails. We believe its fleet could grow to 200 planes in 7 – 8 years.

Figure 1. Amazon Air Flight Network on a Typical Day, April 23, 2020

Flights departing 6 a.m. – 10:59 p.m. in orange; overnight flights in blue

This map shows the origins and destinations of about 90% of Amazon Air’s network on a randomly sampled day, April 23, 2020. Source: Chaddick Institute.

Amazon Air’s network piggybacks off of DHL’s, FedEx’s and UPS’s existing hubs. If Amazon can’t ship you a product by the promised deadline via its own trucks and planes (or via U.S. mail), the package can be turned over to an integrator to do the job. Partially for this reason, we found, the three of the five airports having the most flights, Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International (CVG), Chicago Rockford, and California’s Ontario International, are major hubs for integrators. Even so, Amazon has an uneasy relationship with these more established carriers. Both FedEx and UPS have been grappling for ways to deal with Amazon’s ever-growing presence in the home-delivery business. FedEx even walked away from Amazon traffic last year. Overall, UPS appears to be most vulnerable to Amazon Air’s expansion.

CVG is emerging as the nerve-center of Amazon Air’s operations, being equipped with specialized facilities for package sorting, an arrangement facilitated by an agreement with DHL allowing for the cross-utilization facilities. At this point, Amazon has a less hub-centric design than the integrators. Less than a fifth of its U.S. flights use CVG, a far smaller share of flights than that the share of FedEx and UPS flights using those carriers’ superhubs at Memphis and Louisville, respectively. That could change, however, when the massive CVG complex is ready.

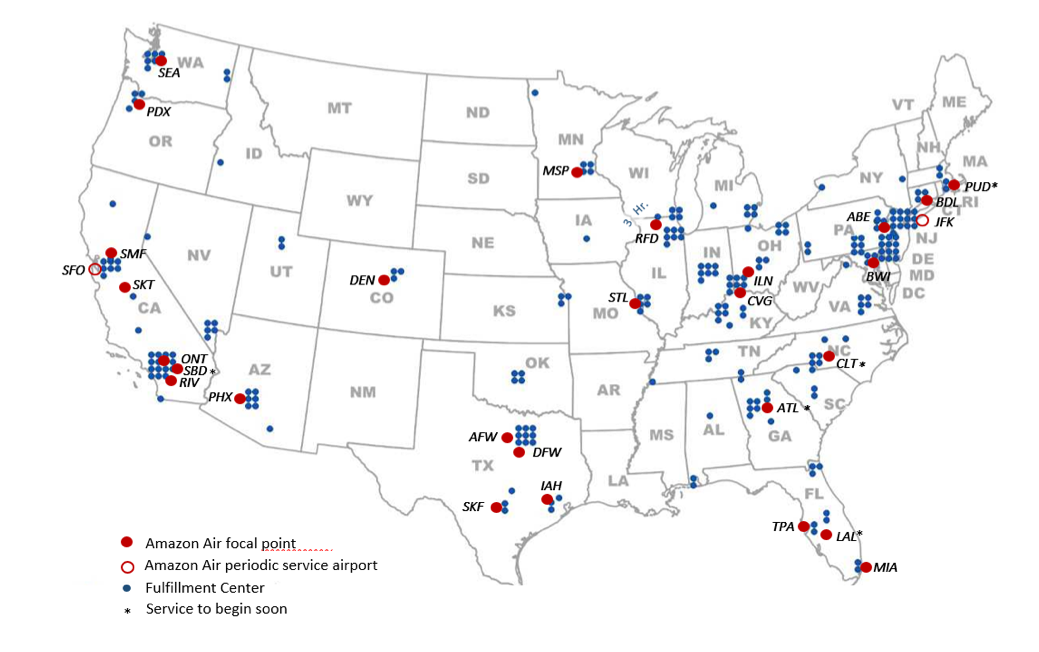

Amazon Air’s growth is good news for advocates of airports dedicated to freight traffic. Such airports have had a tough go of it in recent decades, with some been bypassed by many cargo airlines, which have generally opted for creating hubs at airports, such as Memphis, with a mix of cargo and passenger traffic Six of Amazon’s roughly two dozen operational focal points are airports that are airports with little or no passenger traffic: Chicago Rockford (in Rockford, IL), Fort Worth Alliance (in Dallas, TX), and Ohio’s Wilmington Air Park, which are all hubs, as well as San Antonio’s Kelly Airport, and California’s Stockton and Riverside airports (Figure 2). Among these six, only Chicago Rockford and Stockton have scheduled passenger service. Service to Lakeland Linder International, near Tampa, FL, and San Bernardino, which, too, are bereft of scheduled passenger flights, may begin soon.

Figure 2. Juxtaposition of Airports Served and Fulfillment Centers for Amazon Air

This map shows the proximity of Amazon Air’s airports on the U.S. mainland to its fulfillment centers. The red circles designate airports with Amazon flights, based on a sample encompassing flights on a randomly selected day.

Airports on Map. Lehigh Valley/Allentown/Bethlehem (ABE), Baltimore/Washington (BWI), Charlotte (CLT), Chicago Rockford (RFD), Cincinnati (CVG), Dallas/Fort Worth (DFW), Denver (DEN), Fort Worth Alliance (AFW), Hartford, CT (BDL), Hartsfield -Atlanta (ATL), Houston (IAH), John F. Kennedy (JFK), Lakeland Linder (LAL) Miami (MIA), Minneapolis (MSP), Ontario (ONT), Phoenix (PHX), Portland (PDX), Providence (PVD), Riverside/March Air Reserve (RIV), Sacramento (SMF), St. Louis (STL), San Antonio Kelly (SKF), San Bernardino (SBN), San Francisco (SFO), Seattle (SEA), Stockton (SCK), Tampa (TPA), Wilmington (ILN).

Amazon Air’s use of less-prominent and cargo-oriented airports is driven heavily by its need to connect fulfillment and sorting centers. Although it wants to be within a same-day truck drive to most of the U.S. population, its flights need not to arrive or depart within earshot of the customer. Amazon Air serves the vast New York City market, for example, largely from Lehigh Valley (Allentown-Bethlehem) International Airport hub, which is about 90 miles from Manhattan and handles less than 2% of the passenger traffic as Liberty Newark International. It serves the string of cities between Philadelphia and central Virginia primarily from its Baltimore-Washington International Airport hub. Both are fed by a vast system of trucks and vans.

Amazon Air’s growth will bring many surprises. Don’t expect rival airlines and logistics operators to remain idle as it grabs a bigger piece of the air-cargo pie. Long-established players will increasingly play hardball in negotiations--to the extent their market position allows. But it is noteworthy, at a time when many other airlines are struggling to stem the flow of red ink, that Amazon Air sees blue skies ahead.

Joseph Schwieterman is professor and director of the Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development at DePaul University in Chicago. Schwieterman’s new co-authored study, Insights into Amazon Air: 2020’s Transportation Juggernaut, is available here.

Photo credit: Nathan Coats via Flickr under CC 2.0 License.