From the beginning, California promised much. While yet barely a name on the map, it entered American awareness as a symbol of renewal. It was a final frontier: of geography and of expectation.

—Kevin Starr, Americans and the California Dream: 1850–1915

In the eyes of both those who live here and those who come to observe, California has long stood out as the beacon for a better future. Progressive writers Peter Leyden and Ruy Teixeira suggested last year that our state is in the vanguard of every positive trend, from racial diversity and environmentalism to policing gender roles. “California,” they said in a post on Medium, “is the future of American politics.”

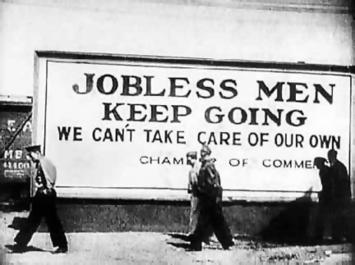

If true, this may not be the best of news. Rather than the vanguard of a more egalitarian future, California has become the progenitor of a new form of feudalism characterized by gross inequality and increasingly rigid class lines, a trend that could be exacerbated in the aftermath of the coronavirus outbreak, which has devastated much of the blue-collar economy. But the shift is likely to only further enhance those at the top of the state’s new class structure, those best suited for the inexorable and expanding shift to digital platforms. These are the tech oligarchs who dominate an economy that leaves most Californians less well off.

The shift to online services is likely to boost the already established large tech firms, particularly those involved in streaming entertainment services, food delivery services, telemedicine, biomedicine, cloud computing, and online education. The shift to remote work has created an enormous market for applications, which facilitate video conferencing and digital collaboration like Slack—the fastest growing business application on record—as well Google Hangouts, Zoom, and Microsoft Teams. Other tech firms, such as Facebook, game makers like Activision Blizzard, and online retailers like Chewy, suggests Morgan Stanley, can also expect to see their stock prices soar as the pandemic fades and public acceptance of online commerce and at-home entertainment grows with enforced familiarity.

Growing corporate concentration in the technology sector, both in the United States and Europe, will enhance the power of these companies to dominate commerce and information flows. As we stare at our screens, we are evermore subject to manipulation by a handful of “platforms” that increasingly control the means of communication. Zoom, whose daily traffic has boomed 535 percent over the past month, has been caught sharing users’ data with other clients without approval.

All this is likely to accelerate the state’s trend towards extreme inequality. Although successors of the state’s entrepreneurial “garage culture,” these firms clearly are not raising all boats and creating opportunities for a broad portion of the population. Instead, according to liberal economist James Galbraith, California is becoming ever more unequal. Although its policies are widely praised on the left, the state now suffers a level of inequality worse than that of Mexico.

The Evolution of California’s Economy

Until the past decade, California boasted a remarkably diverse economy, resting on an array of industries that spanned the gamut from agriculture and oil to aerospace and finance, software, and basic manufacturing. The broad range of opportunities—plus the unmatched beauty and mild climate of the state—lured millions from around the world, from “rocket scientists” to impoverished campesinos. In the process, California developed a large, and increasingly diverse, middle class. “The California century,” notes Ethan Rarick, biographer of Jerry Brown’s father Pat, provided “the template of American life.” There was an American dream across the nation, he wrote, and California was “the proving ground for the American future.”

As recently as the period from 1996 to 2006, according to economist David Friedman, California’s job creation was well distributed among regions, job types, and incomes. But in the recovery after the Great Recession, which hit California more profoundly than the rest of the country, the state’s economy has become more narrowly focused and geographically constrained around the tech-driven Bay Area.

In large part due to the state’s onerous tax burden and regulatory regime, the headquarters of the large energy and aerospace firms that once provided middle class jobs have left California. These include large firms, such as Occidental Petroleum, Jacobs Engineering, Parsons, Bechtel, Toyota, Mitsubishi, Nissan, Schwab, and McKesson, as well as an estimated two thousand smaller companies.

These departures have precipitated a distressing decline in the quality of employment for most Californians. Although California has outperformed the rest of the country in overall employment growth over the past decade, most of the new jobs pay poorly. Overall, the state has created five times as many low-wage as high-wage jobs. A remarkable 86 percent of all new jobs created during this period paid below the median income, while almost half paid under $40,000. Even Silicon Valley has created fewer high-paying, as opposed to low-paying, positions than the national average, and far fewer than prime competitors like Salt Lake City, Seattle, or Austin.

Many of these jobs are particularly vulnerable to Covid-19, future pandemics, and the new attitudes that are likely to emerge as a result. In the pandemic, as everywhere, California’s low-end restaurant and retail workers have been hard hit, but California is particularly exposed to threats to the hospitality, food service, performing arts, sports, and casino sectors. These sectors have accounted for a quarter of all new jobs created this decade, with much of the growth concentrated in idyllic coastal southern California.

In contrast, over the past decade California has fallen to the bottom half of states in terms of manufacturing employment growth, ranking forty-fourth last year; its industrial new job creation declined to less than one-third that of prime competitors such as Texas, Virginia, Arizona, Nevada, and Florida. This has proven a disaster for working-class Californians. Even without adjusting for costs, no California metro ranks in the top ten in terms of well-paying blue-collar jobs, but four—Ventura, Los Angeles, San Jose, and San Diego—sit among the bottom ten.

Even one of the steadiest sources of higher-wage blue-collar employment, international trade, could be severely impacted. International trade, including exports and imports, supports nearly five million California jobs—nearly one in four. Yet, due to regulatory and labor issues, southern California’s ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles have been losing market share to other regions, notably in the South. Reduced trade flows, particularly with China, could have considerable negative effects.

These economic changes have pummeled the middle class—traditionally the bulwark against feudalization. In a recent study conducted by Chapman’s Marshall Toplansky, the vast majority of Californians have a negative net worth, the major exceptions being affluent retirees, people earning over $200,000 annually, and childless college graduates making $100,000 or more per year. The Golden State now suffers the widest gap between middle and upper incomes in the country: 72 percent, compared to a national average of 57 percent.

Silicon Valley: A Feudal Castle Town

As recently as the 1980s, the San Jose area boasted one of the country’s most egalitarian economies. Jobs in manufacturing, assembly, transportation, and customer support helped middle and even working-class families to achieve the California dream. But as Silicon Valley has shifted from an industrial to a software focus, it lost over 160,000 manufacturing positions. Even worse, as much as 40 percent of the current tech workforce is made up of noncitizens, many on temporary visas.

In the process, Silicon Valley has morphed into what CityLab has described as “a region of segregated innovation,” where the rich wax, the middle class declines, and the poor live in increasingly inescapable poverty. San Francisco, which has emerged as a major center of the Bay Area tech scene, has been the place where, according to the Brookings Institution, inequality grew most rapidly among the nation’s large cities in the last decade. The California Budget and Policy Center has named the city first in California for economic inequality; the average income of the top 1 percent of households in the city averages $3.6 million, forty-four times the average income of the bottom 99 percent, which stands at $81,094.

Rather than being a beacon of opportunity, the City by the Bay is a place where the middle-class family heads towards extinction. San Francisco also suffers the highest property crime and petty crime rates of any major urban area, and it has become the epicenter of an explosion in homelessness, even as homelessness has been reduced in much of the country.

For increasing numbers of residents, even massive wealth and unmatched natural amenities are not enough to keep them around. According to demographer Wendell Cox, last year the Bay Area lost an estimated fifty thousand more migrants than came. In 2018, roughly 46 percent of all Bay Area residents indicated they were planning to leave compared to 34 percent just two years earlier. This trend is particularly marked among the young. One recent report from the Urban Land Institute found that 74 percent of all Bay Area millennials were considering a move out of the region in the next five years.

California Is Getting Old

California’s demographics, long driven by newcomers, are changing dramatically. Between 2014 and 2018, notes Cox, net domestic out-migration grew from 46,000 to 156,000. The conventional wisdom among politicians in Sacramento, and their apologists in the press, sees California losing mostly its poor, its elderly, and its less skilled. Yet an analysis of IRS data for 2015–16, the latest available, shows that half of those leaving the state made over $50,000 annually, roughly one in four made over $100,000, and another quarter earned a middle-class paycheck between $50,000 and $100,000.

Perhaps the biggest concern is the loss of young people and families from the state. The largest group leaving—some 28 percent—is between the ages of thirty-five and forty-four, the prime age for raising families. Another third come from those aged twenty-five to thirty-four and forty-five to fifty-four. Sadly, it is among both the young and the more affluent that out-migration is getting stronger.

High housing prices, along with an increasingly dismal job picture, drive this trend. The rise in housing prices, together with soaring rents, has made the California dream all but unattainable for millennials, whose homeownership rates have dropped far below the national average. The salary needed to purchase a mid-priced house in the state has soared to $120,000, the highest on the continent by $30,000, and almost twice what is required to buy a home in Texas, Florida, or Arizona. In San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the homeownership rate among twenty-five to thirty-four-year-olds ranges from 19.6 percent to 22.6 percent—40 percent or more below the national average.

California’s young families increasingly face a toxic combination of high costs and relatively low salaries. Californian millennials on average earn about as much as their counterparts in states such as Texas, Minnesota, and Washington, where the cost of living is far lower. Most seem doomed to spend their lives struggling to pay the rent. Zillow estimates that, for workers between the ages of twenty-two and thirty-four, rent absorbs over 45 percent of income in Los Angeles and San Francisco, compared to roughly 30 percent in Dallas–Fort Worth and Houston. In Los Angeles and the Bay Area, a monthly mortgage amounts to, on average, close to 40 percent of income, compared to 15 percent nationally.

For the next generation of Californians, arguably the best way to buy a home is a distinctly feudal one: win the birth sweepstakes and tap the Bank of Mom and Dad to make a purchase. Approximately one-third of FHA loans in California rely on family money, up from 25 percent in 2011; in some markets, like Los Angeles and Orange County, the rate is close to 40 percent. Overall, coastal California has one of the highest rates of family assistance to renters, well over 35 percent, compared to the national average of 26 percent.

As a result of this process, California’s population growth has all but halted and has fallen below the national average for the first time. In 2015, Los Angeles and San Francisco ranked among the bottom ten in birthrates among fifty-three major metropolitan areas, according to the American Community Survey.

A dearth of young people could pose particular problems for an economy like California’s, long dependent on innovation—which, as economist Gary Becker notes, has historically been the province of younger workers and entrepreneurs. This is occurring while international migration, the other source of demographic dynamism, has slowed to one-third the level seen in Texas, further depressing population growth. As a result, California’s fertility rate has dropped 60 percent more than the national average since 2010, and the state is now aging 50 percent more rapidly than the rest of the country. If these trends continue, wheelchairs will replace surfboards as state icons.

“The Other California”

One of my personal mentors, the late Michael Harrington, challenged America to confront poverty in his book The Other America. What would he think of contemporary California? He would be shocked, in particular, to see that despite the juxtaposition of enormous wealth and poverty, progressives like Laura Tyson and Lenny Mendonca see California as the home of “a new progressive era,” in which the state emerges as the exemplar of social justice.

The statistics for poverty, driven by high costs and diminished opportunities, are shocking. California suffers the highest poverty rate, adjusted for costs, of any state in the country, according to the U.S. Census. A recent United Way study found that close to one in three families in the state are barely able to pay their bills. Fully one in three welfare recipients in the nation live in the California, although it is home to barely 12 percent of the country’s population. Today eight million Californians live in poverty, including two million children, by far the most of any state. This number has risen since the recession, despite the subsequent boom.

The most extreme poverty is found in two places: the vast interior regions and areas close to urban cores. Anyone riding along Highway 33 through the Central Valley can see scenes that seem more like rural Mexico than America: abandoned cars, dilapidated houses, and deserted storefronts. Among the nation’s 381 metropolitan areas, notes a recent Pew study, four of the ten with the lowest share of middle-class residents are in California’s heartland: Fresno, Bakersfield, Visalia-Porterville, and El Centro. Three of the ten regions with the highest proportion of poor people were also in the state’s interior, and all have suffered among the largest rises in inequality.

Economist John Husing, whose work focuses on the Inland Empire, a sprawling region of 4.2 million inhabitants just east of Los Angeles, suggests the state’s green policies have placed it “at war” with industries such as home building, energy, agriculture, and manufacturing that have traditionally driven the interior’s economy. These losses are catastrophic in areas where many residents lack a college education, and five inland California counties have among the lowest percentages of educated workers out of all U.S. metropolitan areas. The Inland Empire, with a population nearly as large as metropolitan Boston, suffers the lowest average pay of any of the nation’s fifty largest counties and has among the highest poverty rates of any of the nation’s twenty-five largest metropolitan areas.

Yet perhaps the most searing poverty can be seen in Los Angeles, by far the state’s largest metropolitan area. The LA area, notes the Census Bureau, has the highest poverty rate of any major metropolitan region. One in four Angelinos, according to a recent UCLA study, spend half their income on rent, the highest again of any major metro area.

Amidst the pandemic, this huge inequality can be seen here and elsewhere in how the virus has hit the state’s poor and minority communities in the biggest urban areas. Despite its density and, for California, high levels of transit dependence, San Francisco has done better than less-dense South Los Angeles in terms of infections and death. (Nowhere has the state come close to New York levels of fatalities.) Similarly, the affluent, tech-oriented, auto-dependent economies of Silicon Valley, West Los Angeles, the South Bay, and Orange County have done far better than the heavily minority inner city. These affluent areas also benefit, as Richard Florida has pointed out, from their plethora of high-end, digitally enabled jobs; the more an economy has this orientation, the easier it has been to limit the pandemic.

Hopefully the virus may bring a novel sense of reality, and even a touch of humility, to state policymakers. “Virtue signaling” steps like outlawing plastic bags have served to spread infection, so much so that San Francisco, the unofficial capital of Ecotopia, now bans reusable totes instead. Other progressive policies, such as allowing vast homeless encampments, are now widely seen less as exercises in tolerance and more as ideal breeding grounds for the virus, as well as more deadly contagions such as typhus. Motivated by the virus, there are finally steps being taken, notably in Los Angeles, to force the homeless off the streets and into safer, more sanitary environments. Among these populations, there are even indications of a return of the signature malady of the Middle Ages, bubonic plague, although the mainstream media seeks to blame this, like most ills, on climate change as opposed to failed social policy.

The Failing Race Card

Perhaps no state advertises its multicultural bona fides more than California. These narratives portray a proudly multicultural California—where Hispanics and African Americans constitute 45 percent of the total population—as the model for future race relations. State attorney general Xavier Becerra has sued the Trump Administration numerous times over immigration policy. The state proclaimed itself to be a sanctuary to all kinds of refugees and migrants; it has already provided driver’s licenses to some one million undocumented aliens, and it has granted free health care to illegal residents. Meanwhile San Francisco, the paragon of wokeness, has moved to allow noncitizens to vote in local elections.

All this may make progressives feel better about themselves, but if the state’s leaders were to look at how people of color are actually doing, they would see something that resembled apartheid South Africa or the pre–Civil Rights South. California, as gubernatorial candidate and environmental activist Michael Shellenberger has suggested, is not the “most progressive state” but the “most racist one.”

Hispanics and African Americans do worse in California than almost anywhere else in the country. Based on cost-of-living estimates from the Census Bureau, 28 percent of African Americans in the state live in poverty, compared with 22 percent nationally. Fully one-third of Latinos, now the state’s largest ethnic group, live in poverty, compared with 21 percent outside the state. Over half of all Latino households can barely pay their bills, according to a United Way study—a figure which rises to 80 percent for undocumented Latinos. “For Latinos,” notes long-time political consultant Mike Madrid, “the California Dream is becoming an unattainable fantasy.”

In the past, poor Californians, whether from the Deep South, Mexico, or the Dust Bowl, could count on the education system to help them advance. But now California has among the lowest reading scores for eighth graders in the nation, and Latino academic achievement is generally lower in California than in the rest of the country. Educators, however—particularly in minority districts—seem more interested in political indoctrination than results. Among the fifty states, California ranked forty-ninth in performance for poor, largely minority, students. San Francisco, the epicenter of California’s woke culture, suffers the worst scores for African Americans out of all counties in the state.

Given meager earnings and the high cost of housing and rent, many minorities are forced to live in deplorable conditions. Out of the 331 zip codes that make up the top 1 percent of overcrowded zip codes in the United States, 134 are found in southern California, primarily in greater Los Angeles and San Diego, and are mostly concentrated around heavily Latino areas such as Pico-Union, East Los Angeles, and Santa Ana in Orange County.

Not surprisingly many minorities, especially African Americans, are considering fleeing the state. In a recent University of California, Berkeley poll, 58 percent of African Americans expressed interest in leaving the state, more than any ethnic group, including whites. Some 45 percent of Asians and Latinos are also considering a move out. These residents may appreciate the state’s celebration of diversity, but increasingly find the state inhospitable to their needs and those of their families.

The Oligarchic Mentality

California’s tech oligarchs may be famously woke, but they do not seem to be greatly concerned by the enormous gaps in class and race in their backyards. The Giving Code, which reports on the charitable trends among the ultrarich, found that between 2006 and 2013, 93 percent of all private foundation giving in Silicon Valley went outside the area. Much of what is given goes to global causes like mitigating climate change, protecting the environment, or fighting diseases in developing countries. Better to be a child in an African village, a whale, or a tree than someone forced to live in their car across the street from Google.

This reflects the oligarchs’ remarkable level of narcissism, elitism, and self-regard. As Thomas Piketty has observed of some nineteenth-century industrialists, the tech oligarchs believe that the rise of technically trained people would “destroy artificial inequalities” in favor of highlighting “natural inequalities.” They justify their position by embracing the notion that they are not just creating value but working to “change the world.” This makes them—unlike the merely profit-oriented old managerial aristocracy or the grubby corporate speculator—intrinsically more deserving of their wealth and power.

These tech oligarchs do not oppose huge class divisions; rather, they embrace what Aldous Huxley called “a scientific caste system,” in which they stand at the apex. In some ways, this reflects the realities of the current tech business, which relies not on a wide range of skills but on a small cadre of elite “talent.” This is very different from the demands placed on managers in more traditional businesses who had to cope with not only other managers, but also marketers, technicians, warehouse workers, and salespeople. In some fields, such as manufacturing and energy, they often confronted unionized workers who could advocate for their own rights. In contrast, tech firms are rarely unionized.

The Road to Oligarchic Socialism

Rather than fight inequality, the oligarchs are seeking ways to accommodate it. Gregory Ferenstein, who interviewed 147 digital company founders, says most believe that “an increasingly greater share of economic wealth will be generated by a smaller slice of very talented or original people. Everyone else will increasingly subsist on some combination of part-time entrepreneurial ‘gig work’ and government aid.” These oligarchs generally don’t even expect their workers or consumers to achieve greater independence through the traditional avenues of owning houses and starting companies. If anything, they tend to push what might be called an anti-materialist point of view that emphasizes “meaningful community” on a global scale but rarely speaks of upward mobility.

Ferenstein suggests that many oligarchs, in contrast to business leaders of the past, seek to secure their future by creating a radically expanded welfare state. Indeed, the former head of Uber, Travis Kalanick, Y Combinator founder Sam Altman, Mark Zuckerberg, and Elon Musk all favor a publicly funded guaranteed annual wage—in part to help allay fears of potential insurrection arising from the effects of “disruption” on an exposed workforce. In a sense, the oligarchs have embraced the old aristocratic notion of what Marx called a “proletarian alms bag” by having taxpayers provide not just guaranteed wages but free health care, free college, and housing subsidies. This alms bag may need to be made even larger after the disruption of much of the middle- and working-class economies in the wake of Covid-19.

This oligarchic socialism differs dramatically from the mixed capitalist system that emerged after the Second World War, which was based on increased upward mobility and increased consumption for the masses. In the world envisioned by the oligarchs, the poor would become ever more dependent on the state, as their labor is devalued by regulatory assaults on the industrial economy, as well as by the greater implementation of automation and artificial intelligence. Even those lucky enough to work for the oligarchs will face a severely restricted future. Unable to grow into property-owning adults, these workers will subsist on subsidies and what they can make through gig work; to combat boredom, they can enjoy what Google calls “immersive computing” in their spare time.

The Alliance with the Clerisy

To cement their dominion, the oligarchs have made political alliances with other groups, notably those who dominate California’s increasingly one-party system. This has made them critical allies of California’s progressives, with whom they have made common cause on a host of issues, from gender rights to immigration to climate change.

This alliance between the oligarchs and California’s clerisy—university professors, senior bureaucrats, and nonprofits—drives the state’s powerful green agenda. Oligarchic firms such as Google and Apple have embraced the basic thrust of the state’s climate policies. Time magazine, for example, which is owned by Salesforce founder Mark Benioff, recently named the Jeanne d’Arc of the Greens, Greta Thunberg, its Person of the Year.

Unlike most Californians, Benioff and other oligarchs can afford their environmental radicalism; their businesses do not depend primarily on affordable energy or large pools of moderately skilled workers. Similarly, the clerisy, cloistered in powerful institutions like academia, the media, or government, are largely insulated from the ill effects of the regulatory regime, which include higher energy and housing prices.

California’s green regulators maintain that the implementation of ever stricter rules related to climate will have only a small impact on the economy, a contention that even some environmental economists, such as Harvard’s Robert Stavins, find dubious. Indeed, a recent analysis by attorneys David Friedman and Jennifer Hernandez demonstrates in detail how California’s draconian anti–climate change regime has exacerbated economic, geographic, and racial inequality. Among the primary impacts of climate regulations, as laid out by Friedman and Hernandez, has been the elimination of historically well-paying jobs in fields such as manufacturing, energy, and home building—all key employers for working- and middle-class Californians.

Ironically, California’s efforts to save the planet have actually done little more than divert greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to other states and countries. Since 2007, when the Golden State’s “landmark” global warming legislation was passed, note Friedman and Hernandez, California has accounted for barely 5 percent of the nation’s GHG reductions, and the state ranks a mediocre fortieth in per capita GHG reduction over the past decade. As Friedman and Hernandez demonstrate, state policies may be increasing total GHG by pushing people and industries to states with less mild climates.

Given that, in 2010, California accounted for less than 1 percent of global GHG emissions, the disproportionately large reductions sought by state activists and bureaucrats would have no discernible effect on global emissions under the terms of the Paris Agreement. “If California ceased to exist in 2030,” Friedman and Hernandez note, “global GHG emissions would be still be 99.54 percent” of where they would be otherwise.

A State of Delusion

Even if it does little for the planet, the state’s climate alarmism serves an important political purpose. Like medieval clerics pointing to the heavens for every problem, California’s leaders use climate change to excuse virtually every failure of state policy. During the 2011–17 California drought, Governor Jerry Brown and his minions blamed the climate for the dry period, but avoided taking blame for insufficient capacity for storage that would have helped farmers. And when the rains came back and reservoirs filled, negating their narrative, little attempt was made to save water for the inevitable next drought.

Similarly, in the case of the recent wildfires, Gavin Newsom and his claque in the media blamed changes in the global climate. But it had at least as much to do with green resistance to controlled burns and brush clearance than anything happening on a planetary scale; attempts to impose such fuel controls had been vetoed by Brown and are opposed by the greens and their allies at media outlets like the Los Angeles Times.

Climate alarmism is also useful to cloak the political failures of local politicians like LA mayor Eric Garcetti. Given his city’s mind-boggling congestion, rampant inequality, massive rat infestation, and ubiquitous homeless camps, it’s no surprise that he would rather talk about becoming chair of the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. And climate activism may even provide the rationale for the ambitious Governor Newsom to run for president.

Unlike traditional businesses, the tech oligarchs not only endorse but even profit from the state’s incessant climate virtue signaling. Renewable energy may be expensive and unreliable, but state policy enriches the tech oligarchy’s green energy investments, even when their efforts—like the Google-backed Ivanpah solar farm—fail to deliver affordable, reliable energy. In contemporary California, results matter less than supposed good intentions.

Is There a Way to Counter the New Feudalism?

Until now, the alliance of the oligarchs with the progressive clerisy, almost unanimously supported by the media, has been all but immune from challenge. Yet there exist in this alliance what Marxists might call fundamental “contradictions” that could eventually undermine the cozy arrangement between the rapacious capitalists of the Valley and their militant progressive allies.

This can be seen in growing conflicts between the oligarchs and the state’s increasingly assertive Left. The youth activists now at the forefront of the anti–climate change movement may be less willing to tolerate the oligarchy’s personal excesses than previous generations of environmental advocates. After all, if the world is on the verge of a global apocalypse, how can the luxurious lifestyles of those flying their private jets to discuss this “crisis,” like Leonardo DiCaprio or the heads of Google, be tolerated?

Unlike gentry progressives, increasing numbers of climate activists marry green values with explicit socialism. Many endorse the view of Barry Commoner, one of the founding fathers of modern environmentalism, that “Capitalism is the earth’s number one enemy.” There’s even a growing socialist movement among tech employees in Silicon Valley, many of whom have little chance of replicating the opportunities for wealth accumulation enjoyed by prior generations in the Bay Area.

The class dimension has become more evident in the increasingly progressive-dominated, veto-proof legislature. The recently passed Senate Bill 5, concerning contract labor, is a direct threat not only to tech firms like Uber and Lyft, but to companies in everything from media to trucking who subcontract services from smaller companies and individuals. And proposals for higher income and other taxes will also certainly hit the tech workforce. In response to such changes, some tech firms have already started shifting employment to other states. In fact, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates, several states—Idaho, Tennessee, Washington, and Utah—are now growing their tech employment more rapidly than California.

Another threat to the new feudal order lies in the simmering resentments of the state’s now largely forgotten middle and working classes. Only 17 percent of Californians, according to one recent survey, believe the state’s current generation is doing better than previous ones; more than 50 percent think Californians 18–30 years old are doing worse than older cohorts.

These resentments may not be articulated but they definitely lie beneath the surface. More Californians feel the state is headed in the wrong direction than the right one, according to a recent poll by the Public Policy Institute of California, a number that reaches above 55 percent in the inland areas. Nor is support for the current political regime particularly deep. Voters dislike the state legislature even more than President Trump.

There’s even—despite the almost unceasing media hype—a growing reaction against the state’s draconian climate policies. Attempts to ban natural gas, for example, have elicited opposition from 110 cities, with a total population of over eight million. The California Chamber of Commerce and the three most prominent ethnic Chambers—African American, Latino, and Asian Pacific—have joined the opposition.

Increasingly in California, as in other parts of the world, previously sacrosanct climate change policies risk a class-based backlash. Some of this opposition also arises from civil rights organizations, who are finally awakening to the impact climate extremism has on their constituents. Recently, some two hundred veteran civil rights leaders sued the California Air Resources Board on the ground that state policies are skewed against the poor and minorities.

But perhaps the biggest threat to California’s emerging feudal order may be financial. As even Jerry Brown noted, the Johnny-one-note tech economy could stumble, a possibility made more real by the recent $100 billion drop in the value of privately held “unicorns.” Already over two-thirds of cities in California do not have any funds set aside for health care and other retirement expenses. The state also suffers a trillion-dollar pension shortfall, as has been noted by former Democratic state senator Joe Nation. Overall U.S. News places California forty-second in fiscal health among the states, despite the tech boom.

What California needs today is not some imagined return of Reaganite conservatism—that ship long ago sailed over the horizon—but a policy agenda that, first and foremost, serves the basic interests of state residents by expanding opportunity across both classes and geographies. Those of us concerned about a better future for the next generation may be discouraged, but it is hard to accept that, with all our great resources and culture of innovation, a way cannot be found to restore the state’s once proud reputation as an incubator of aspirations and fulfiller of dreams.

This piece originally appeared in American Affairs Volume IV, Number 2 (Summer 2020): 62–77.

Joel Kotkin is the author of the just-released book The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute — formerly the Center for Opportunity Urbanism. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin

Photo credit: Mike Licht, via Flickr under CC 2.0 License