Last spring, the COVID-19 pandemic caused perhaps the worst job losses since the Great Depression. The decrease in the labor force participation rate — from 63.3% to 61.3% — has been steeper than that seen in the Great Recession and is among the largest 12-month declines in the post-World War II era, according to the Pew Research Center and federal labor data.

But for all the pain, this terrifying year could augur potentially positive changes in the workplace. Pandemics change economies, a truth going back centuries. The post-COVID period may well see a transformative, long-lasting effect on employers.

The shifting balance between employers and workers was evident before the pandemic, with wages for the first time in decades rising for lower-income laborers. While the unemployment rate is over 6% and the country had 8 million fewer positions in March than before the pandemic, there’s still a growing shortage of workers and 7.4 million unfilled jobs.

Some of this is due to demographic shifts caused by lower birthrates; U.S. population growth for ages between 16 and 64 has dropped from 20% in the 1980s to less than 5% in the last decade. Some conservatives blame the stimulus package and extended unemployment for workers for the current labor shortage. Others, such as former Obama chief economist Jason Furman, also blame wariness connected to the virus.

But whatever the causes, the tighter labor market gives workers more leverage with employers, allowing even lower-end service workers to demand signing bonuses, higher wages and more humane working conditions.

White-collar workers also face a new reality. Once dragooned into offices often far from affordable homes, they have adapted to new hybrid models, with remote work being done from home, dispersed offices and coffee shops.

Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom suggests 20% of work will be done from home even after the pandemic ends, up from 5% in 2019. Various studies also show that remote workers have been more productive — a result business executives welcome along with lower office space costs.

However, others — people at the top of the corporate ladder, leasing agents, owners of commercial office space — are already pushing people back to the cubicle. JPMorgan Chase’s CEO Jamie Dimon thinks workers should go back to the office, but this may not be so appealing to workers who have finally ditched their long commutes.

Read the rest of this piece at Los Angeles Times.

Joel Kotkin is the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.

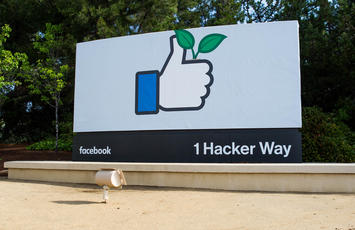

Photo: Anthony Qunitano, via Flickr under CC 2.0 License. Facebook recently announced that all of its employees can request to work from home permanently.