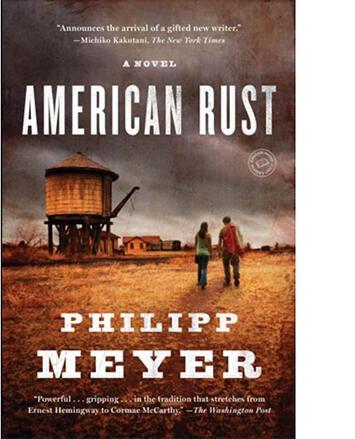

In the new Showtime series, American Rust, set and filmed outside of Pittsburgh, PA, and based on the 2009 novel by Philipp Meyer, we see the aftermath of an industrial collapse so devastating that the fictional town of Buell, PA, looks like it’s been bombed, strafed, and ransacked. In the novel, middle aged seamstress Grace remembers how when steel went belly up, the blast furnaces in the town were destroyed with dynamite. Shortly after that, the World Trade Center was blown up, too. “It wasn’t logical, but the one reminded her of the other.”

Both versions of American Rust follow the stunted dreams of Billy, a washed-up high school football star who inexplicably turns down a college football scholarship to Colgate University, and Isaac, a physics genius, who, rather than trying to get into Yale, as his older sister has done, steals $4,000 from his disabled father and plans to hop a train to California. In both versions Billy and Isaac take refuge in the hollowed out shell of Carrie Furnace, run into some bad dudes, and pretty soon there’s a dead body. Police chief Del Harris wants to protect Billy and Isaac from the law, in part because he’s known them his whole life, but also because he’s sweet on Billy’s mom, Grace.

Jeff Daniels, as Buell Police Chief Del Harris, brings a lot of star power to American Rust. He is wry and taciturn and world weary. He acts according to his own moral code. Maura Tierney, as Del’s erstwhile girlfriend and Billy’s mom, Grace, pops and crackles on the screen.

As someone who studies how working-class people are represented on film and television, and who lives just down the road from Carrie Furnace, I’m thrilled to see a show like this come to prestige cable. American Rust has big stars, a talented cast, good writing, gorgeous production values, and relevant themes.

But American Rust is stuck in the past. It’s not really about the working class of today, but, rather, the shattered dreams of the working class of the 20th century. Sherry Linkon, in her book The Half-Life of Deindustrialization, explains how masculinity works in novels like American Rust. Linkon argues that young men like Billy and Isaac, deprived of the surefire path of their fathers’ generation in the factory or the mine, are “lacking economic opportunity,” and because of that, they also lack a “clear sense of how to be a man.” She argues that Meyer represents the structural problems Billy and Isaac face, but that his characters mostly blame themselves for their tragic demise. While Billy’s “life chances are clearly constrained . . . by deindustrialization,” Linkon writes, “he interprets those limitations in very personal ways.”

Ironically, perhaps, Meyer wanted his novel to be a critique of this tendency towards self-blame. Towards the end of the novel, Meyer writes, “there was something particularly American about it—blaming yourself for bad luck—that resistance to seeing your life as affected by social forces, a tendency to attribute larger problems to individual behavior. The ugly reverse of the American Dream.”

Showtime’s version of American Rust makes some significant changes to Meyer’s story, but it doubles down on the idea that post-industrial failure is personal. The opening scenes show all the main characters escaping through substances in one way or the other—weighing out prescription opioids, pushing a loved one to take a sleeping pill, drinking a tall Pabst Blue Ribbon out of a can, or crunching ibuprofen, because, Grace explains, she “likes the taste.” These people have given up; they seek relief from pain, above all else. The focus on substance abuse, and, especially, opioids, is one of the ways that Showtime’s American Rust brings the 2009 storyline into the present.

Read the rest of this piece at Working-Class Perspectives.

Kathy M. Newman is an Associate Professor of English at Carnegie Mellon University and author of Radio-Active: Advertising and Activism 1935-1947.