In 1976, my ethnically diverse, working-class county where blue-collar union households worked in factories and refineries, owned homes and sent their kids to college, agreed to string a 6-mile long fire hose across the Richmond Bridge to supply water to California's wealthiest and whitest county. Marin's vitriolic anti-housing Green advocates had successfully blocked all water supply augmentation infrastructure upgrades for decades. The Marin greens are Proud to have made housing illegal on more than 80% of the County, and remain righteous about their progressive liberalism notwithstanding a federal enforcement action confirming widespread residential racial segregation (in 2010) that persisted a decade later (2019), and even though one of its wealthiest cities broke the state's 50-year compliance track record when it intentionally segregated its elementary schools by race (in 2019).

Nevertheless, when these rich folks needed water they paid to take some of ours.

I now spend most of my time in Southern California, where I teach law students about environmental justice and civil rights, and work first to get housing approvals and then defend the approvals from California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) lawsuits.

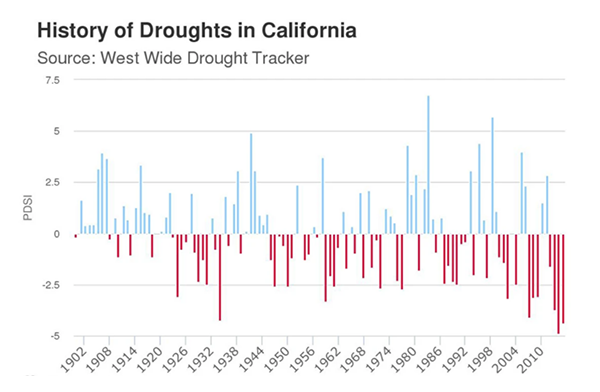

California law makes it illegal to build housing if there's not enough water. California has not, in recorded history, has a "normal" rainfall year - we have big wet (and big dry) years - as the history graph below shows. Our mostly kind climate also produces rainfall seasonally, with long dry summer sunshine. The Sierra Nevada snowpack stores some water, but engineered and managed water storage and conveyance systems have been and remain essential for human survival — and upward mobility.

By the early 1970s, the state’s first 20 million overwhelmingly white residents built and prospered from a world-class network of reservoirs and aqueducts indispensable for living in a desert with massively variable precipitation. Since then, the state added nearly another 20 million people, almost entirely Latino, Asian and other minorities. Starting in the 1970's, though, politically influential white activists have blocked virtually all major new water storage and distribution system improvements, including those that are essential for providing new, less affluent families with affordable, reliable water.

Today, even moderately dry conditions (60 to 80 percent) of "normal" rainfall years are enough to trigger yet another emergency declaration, demand for water use cutbacks, and panicked polls ranking water supply as the top environmental concern instead of wildfires and climate change. Water shortfalls also block new housing in a state where housing-induced poverty rates are the worst in the United States.

Water supplies, treatment, and distribution systems are the most robust in locations serving the state's wealthiest elites, starting of course with San Francisco's destruction of Yosemite National Park's north valley. In contrast, as recently reported by the non-partisan California State Auditor, nearly one million Californians don't have safe tap water - a group that is overwhelmingly comprised of Latinos and other communities of color in the Southern and Central Valley regions.

California's unwillingness to meet the water needs of its second 20 million residents is a civil rights disgrace. Millions of people suffer third-world water poverty while activist-induced “water scarcity" is used by the wealthy to prevent even affordable housing.

The rise of white environmental activism, and the refusal to improve essential water infrastructure, closely tracks the state’s dramatic shift from a majority white to a minority-majority society. California's population grew to 20 million people in 1970 and was nearly 80 percent white. The first 20 million understood that they could not prosper in a drought-prone state without building reservoirs and aqueducts to capture highly uncertain rainfall and snowpack runoff (see Chart).

In 1913, Los Angeles took over its water supply from a private water profiteer and built the first 200 miles of an aqueduct shipping water from the Owens Valley. In the same year an act of Congress allowed San Francisco to dam and convey pristine Sierra water from the newly-created Yosemite National Park, an achievement Bay Area leaders hail as their “birthright.”

State and federal projects expanded California’s water system to more efficiently capture and convey water from the wetter north and eastern Sierra foothills to drier, booming California coastal communities and Central Valley farms. Shasta Lake, an inland sea on the Sacramento River, was first filled in 1945. The nation’s highest dam at Oroville was completed in 1968.

Technical challenges were immense, but the state persisted. As water supplies became more reliable, the first 20 million flourished. In 1960 homeownership rates reached California's historic high of nearly 60 percent. Unemployment fell to just 4 percent by 1970.

Everything changed after 1970, just as California’s white population started declining to just 35 percent of the state by 2020. Yet, this shrinking, elderly minority, in the name of the environment, continues to deny the same water security they enjoyed for the state’s younger, now majority-minority residents.

It is a shocking civil rights offense. The last large state or federally funded reservoir was built in 1979. For nearly 50 years, even impeccably green Democratic governors like Jerry Brown Jr. and Gavin Newsom have unsuccessfully tried to build critically-needed conveyance between state and federal freshwater pumps on the south side of the Sacramento delta with reservoirs to the north. Even as they claim that the water system must be modernized as climate change causes deeper droughts, bureaucrats empty precious water from state reservoirs for speculative, as yet ecologically ineffective, species protection programs.

In 2014 and 2018, voters approved $11.5 billion in water bonds, but only $2.7 billion was earmarked for new water storage — the vast majority was earmarked for eco-system restoration or conservation. Even then, state bureaucrats eventually declined to support two long-proposed major new reservoirs, and the smaller projects they seem willing to pursue aren't scheduled to be operational for years.

If not preemptively squelched by timid officials, activists delay and often bankrupt new water facilities with decades-long environmental review and lawsuits. A Huntington Beach desalination plant was stalled by well-funded environmental opposition since 1998 and was killed earlier in 2022 by longstanding anti-growth Coastal Commission members. Although Governor Newsom was on record supporting the project, not even his own Commissioners agreed. Since 2000, Israel, constructed 5 desalination facilities producing nearly 500,000 acre-feet per year and plans to double capacity by 2030 - and a San Diego's leaders secured approval for their desalination plant, but a stable supply of clean water for the state's largest region was again killed by elites. Almost no water banks, reservoirs, aqueducts, existing dam and reservoir expansions and other improvements survive this implacable green opposition.

California activists insist that mandatory cutbacks, conservation, and the poorly-labeled "toilets to tap" potable re-use of sewage flows are the only acceptable responses to the water scarcity they have caused. The state's green legislative and regulatory leaders are quietly working to impose ever more restrictive daily water use "standards" on state residents. But these measures are inherently regressive and hurt poor, minority families already paying exorbitant rent and energy bills much more than older rich white homeowners. The state’s affluent have long proved willing to ignore water conservation mandates, even at the height of the worst drought in history, and simply pay more to maintain the acres of lawns and gardens gracing their mansions.

In modern California, which hosts the nation’s largest cadre of billionaires, an astonishing 18 percent of all residents cannot afford water for basic needs like cooking, washing, and drinking. More than 36 percent of state residents—about 14 million people-- the vast majority of which are Latino or Black, live on less than twice the federal poverty income level. State officials believe that as many as 34 percent of these residents need assistance just to cover skyrocketing water costs.

Unreliable water also entrenches the state’s racist homeownership and commuting impacts. Wealthy white residents in places like Pebble Beach, aided by compliant bureaucrats and courts, are learning that claims of “water scarcity” can defeat affordable housing they don’t want in their communities. Minority workers serving the rich are forced to live and commute from distant, disadvantaged communities like Castroville, where environmental and conditions steadily degrade and the less affluent are burdened with rising fuel costs to work.

The state’s wealthy whites acquired their homes, raised families and are entering retirement having disproportionately benefitted from water engineering marvels constructed when they were the majority population. To date, their signature legacy is making life worse for California’s subsequent minority-majority population by denying water, the most basic of all human and civil rights, for the state’s newest 20 million residents. The state must cease privileging the concerns of the aging white environmentalists and instead work just as hard as it did in the past to secure affordable, reliable water for everyone else.

Jennifer Hernandez is a partner at Holland & Knight. Ms. Hernandez has practiced land use and environmental law for more than 30 years, and leads Holland & Knight's West Coast Land Use and Environmental Group.

Photo: California Aqueduct via Wikimedia under CC 3.0 License.