With federal approval of New York’s environmental assessment, most of the federal, state, and local obstacles to New York City’s cordon pricing plan — which almost everyone erroneously calls a congestion pricing plan — have been removed. But there is still one more: New Jersey is suing to stop the plan because New Jersey residents would pay a large share of the costs yet get few of the benefits. As several New Jersey legislators have accurately pointed out, the plan “is nothing more than a cash grab” aimed at helping to close the deficit of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) and specifically the subway system, which New Jersey drivers would rarely use.

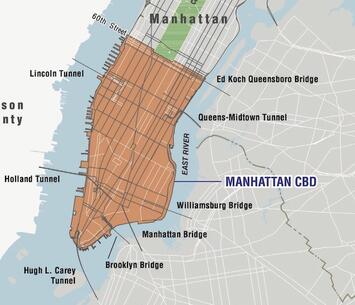

The plan calls for charging anyone who drives into Manhattan south of 60th street between 6 am and 10 pm to pay $23. This is expected to earn $1 billion a year, all of which would go to the MTA to help cover its $2.5 billion annual deficit. Low-income people would be able to use the amount they pay as a tax credit, but if they are low income they probably aren’t paying much in taxes. New Jersey residents would pay the $23 instead of, not on top of, existing tolls, which effectively increases their cost of entry into Manhattan by 56 percent. Taxi and other for-hire drivers would pay the fee just once a day even if they recross the cordon several times.

This is not a true congestion pricing plan. True congestion pricing varies the fee by the amount of congestion. While the cordon pricing plan calls for lower fees at night, Manhattan, like other places, has more congestion in the early morning and early evening hours than mid-day or, say, 8 pm to 10 pm. A more variable fee would lead some people to travel earlier or later in order to avoid the peak fees, thus spreading out traffic. Fees should also vary by roadway, not for an entire district.

While the MTA points to London’s cordon pricing as a great success, the New York Post calls London’s program a “disaster.” The Post points out that, several years after adopting the plan, London now is rated at having worse congestion than New York City. In fact, INRIX rates London’s as the worst in the world as it costs the average motorist 155 hours of wasted time per year, compared with 117 for New York.

Cordon pricing may produce a one-time-only reduction in traffic. But in an area where traffic is growing, cordon pricing won’t stop it from becoming congested again. Research has found that cordon pricing will persuade some employers to move out of a cordoned district, while it may encourage some residents to move in. If this happens, then New York subway riders from the outer boroughs into Manhattan will decline, thus defeating the purpose of propping up the subway system.

While New Jersey officials fret about the impacts of the cordon pricing plan on New Jersey commuters, I suspect the state wouldn’t have objected to increased tolls if they had been cut in on a share of the revenues. MTA really doesn’t have any money to share, but if New Jersey’s lawsuit proves to have any traction in court, it will probably agree to give New Jersey a portion of the increased tolls from the Holland and Lincoln tunnels.

This piece first appeared at The Antiplanner.

Randal O'Toole, the Antiplanner, is a policy analyst with nearly 50 years of experience reviewing transportation and land-use plans and the author of The Best-Laid Plans: How Government Planning Harms Your Quality of Life, Your Pocketbook, and Your Future.

Photo: Courtesy The Antiplanner.

Long Island

Interests on Long Island (which includes Queens and Brooklyn) also oppose the fee, and prefer to retain free bridge access to Manhattan. The fee is a half-step toward applying a price on their connections.