Two distinct expressions of urbanism, the global city and the mega city, are often conflated in the public’s mind. This can lead people to implicitly link the future fortunes of megacities (urban regions of more than 10 million people) with the success of global cities (defined roughly as a very important node at the high end of the global economy), especially as there’s overlap between the two types. They can then assume that the world’s emerging megacities will ultimately be successful, maybe even very successful. Places like São Paulo and Istanbul are held up as global cities in the making. Even more clearly struggling megacities like Jakarta and Lagos are sometimes portrayed as up and coming hip.

But in reality most emerging megacities likely will never turn the corner to developed status and achieve a decent standard of living and quality of life for their residents. They may be important national centers of aspiration, but most of them will never become influential global cities. Their huge size and vast problems will leave them with perpetual entrenched poverty, poor infrastructure and public services, and low quality of life by global standards.

The general rule seems to be that a megacity can only achieve escape pervasive dysfunction if they are a major city in a country that is the world’s current rising economic (or historically imperial) power.

|

Rank |

City |

Population |

|

1 |

Tokyo-Yokohama, Japan |

37,555,000 |

|

2 |

Jakarta, Indonesia |

29,959,000 |

|

3 |

Delhi, India |

24,134,000 |

|

4 |

Seoul-Incheon, South Korea |

22,992,000 |

|

5 |

Manila, Philippines |

22,710,000 |

|

6 |

Shanghai, China |

22,650,000 |

|

7 |

Karachi, Pakistan |

21,585,000 |

|

8 |

New York, USA |

20,661,000 |

|

9 |

Mexico City, Mexico |

20,300,000 |

|

10 |

São Paulo, Brazil |

20,273,000 |

|

11 |

Beijing, China |

19,277,000 |

|

12 |

Guangzhou, China |

18,316,000 |

|

13 |

Mumbai, India |

17,672,000 |

|

14 |

Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto, Japan |

17,234,000 |

|

15 |

Moscow, Russia |

15,885,000 |

|

16 |

Los Angeles, USA |

15,250,000 |

|

17 |

Cairo, Egypt |

15,206,000 |

|

18 |

Bangkok, Thailand |

14,910,000 |

|

19 |

Kolkata, India |

14,896,000 |

|

20 |

Dhaka, Bangladesh |

14,816,000 |

|

21 |

Buenos Aires, Argentina |

13,913,000 |

|

22 |

Tehran, Iran |

13,429,000 |

|

23 |

Istanbul, Turkey |

13,187,000 |

|

24 |

Shenzhen, China |

12,860,000 |

|

25 |

Lagos, Nigeria |

12,549,000 |

|

26 |

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil |

11,723,000 |

|

27 |

Paris, France |

10,975,000 |

|

28 |

Nagoya, Japan |

10,238,000 |

|

29 |

London, United Kingdom |

10,149,000 |

Table 1: World’s Megacities, 2010, based on urban agglomeration size. Source: Demographia World Urban Areas, 10th Edition (May 2014)

This is the case with most developed world megacities. Moscow was the capital of the Soviet Empire. New York and Los Angeles came of age when America was the rising, and ultimately dominant, economic colossus. It’s the same for Paris and London, two borderline megacities, which rose as imperial capitals. London remains arguably the premier global city in the world.

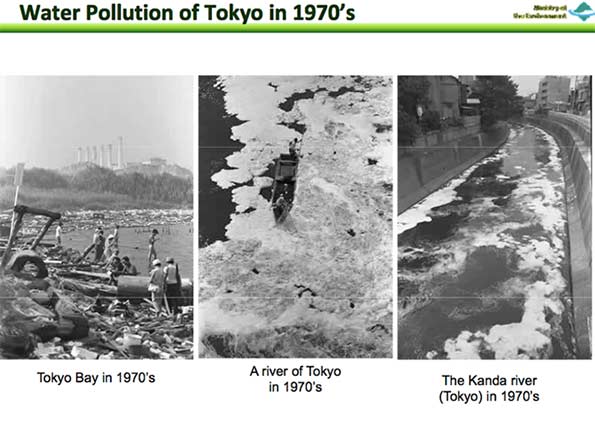

But it’s also true of other megacities you might not consider. Tokyo only achieved its fully developed state when Japan was the rising power. Until fairly recently, much of Japan’s capital was backwards by developed world standards. For example, despite Japan’s famously high tech toilets, even in the inner 23 wards of Tokyo it was only in 1995 that 100% sewer service was achieved. In the second edition of Peter Hall’s landmark book The World Cities, he describes a 1970s Tokyo in which the night soil pickup industry was alive and well. Only in an era of national economic hyper growth – culminating in the 1980s – was Japan able to fully modernize its urban infrastructure and clean up the massive environmental problems resulting from its rapid industrialization and urbanization. This was the time when Japan seemed destined to become the world’s leading economic power, and America was fretting as Japanese investors bought trophy assets ranging from Columbia Pictures to Rockefeller Center.

Image from 2011 presentation by Takatoshi Wako, “Night Soil Management and Decentralized Wastewater Treatment Systems in Japan”

We are witnessing the same today in China. It’s no accident that cities like Beijing and Shanghai are becoming fully modernized at the same time that China is the world’s rising economic power. Even there, serious problems with social integration, pollution, and low quality development remain. China had best hope its economic growth continues until such time as it’s rich enough to solve those problems too.

Apart from the developed West, Japan, and China, only one world megacity has ever pulled off the transition to full modernity is Seoul. Seoul, however, followed a similar trajectory to Tokyo. Destroyed in the Korean War, it was rebuilt with the help of massive foreign aid. As dictatorship gave way to democracy, South Korea emerged as the leading “Asian Tiger” economy, a sort of mini-Japan. Yet it’s only recently that Seoul has begun to transcend its soulless apartment towers and focus on building a quality of life to match its advanced subways and broadband networks, for example, by uncovering a stream previously channeled underground into storm sewers to create an attractive greenway.

Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul, daylighted in 2005. Image: Wikipedia

The world’s other megacities, sadly, are located in countries on a less positive trajectory. Many of them are in impoverished developing countries in South and Southeast Asia and Africa. Others are in economies like the BRICs once touted as emerging powers, but many of which , have badly stumbled. India and Brazil are not following the path of Japan and South Korea – not even that of China. Their economies are large and in a sense important, but face massive structural challenges.

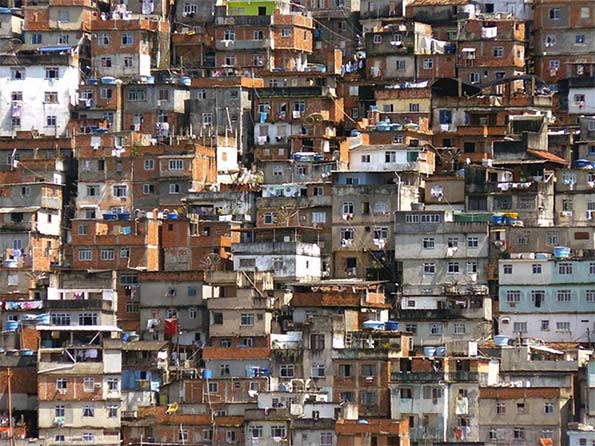

Pavãozinho favela, Rio de Janeiro. Photo: Wikipedia

Brazil is planning a coming out party with the World Cup and Olympics. The city of São Paulo has even established its own foreign ministry to develop direct diplomatic and other ties with countries overseas to flex its global muscles. Yet the social reality is less impressive: Paulistanos rioted last year in response to transit fare increases. Income inequality in São Paulo is stark, and public safety very questionable. Rio has numerous favelas where military style units are trying to establish basic security, albeit with heavy handed tactics. Rowers training for the Olympics have described Rio’s waterways as the most polluted they’ve ever seen, with one of them telling the New York Times, “I’ve never seen anything like this before.” In next door Argentina, once wealthy Buenos Aires continues to decay along with the nation, the consequences of lengthy misrule.

Dharavi slum, Mumbia. Photo: Wikipedia

But problems in Latin America’s megacities pale next to those elsewhere. In India’s financial and commercial capita of Mumbai, over half the population lives in slums. Delhi was recently noted as having the world’s worst air pollution. Dhaka, Bangladesh is both impoverished and has extreme flooding problems. Karachi, Manila, and Jakarta suffer severe poverty and infrastructure problems. Large African cities like Lagos can’t overcome the basic development problems of the continent.

Shantytown in Manila. Photo: Wikipedia

Some argue that these megacities are actually opportunities zones for their country and even that their slums should be praised - or might eventually, as one article claimed, save the planet. After all, people are voting with their feet to move there. Perhaps that’s true in some sense, though some of the advantage of cities stems from a decline in the viability of rural life.

But the problem is that there’s no clear path to prosperous maturity for these megacities. They are so huge, and their problems so immense that they are difficult to even conceptualize, much less do something about. The amount of needed infrastructure provision alone – water, sanitation, drainage, transport, telecom, electricity, parks, schools, etc. – is staggering. And that doesn’t even touch arguably more difficult problems like corruption and good governance. Absent national hyper growth – a la Japan or Korea – of a level that creates a plausible claim to being the world’s rising economic power, or the proceeds of empire, it seems unlikely any of these cities will ever succeed. By contrast, smaller cities have a much more addressable problem space.

Megacities may have their virtues and short term advantages, but unlike yesterday’s imperial or economic capitals like New York and Tokyo, today’s emerging world megacities will have a hard time even achieving the basics of urban quality of life, much less succeed in rising to join the world’s elite.

Aaron M. Renn is an independent writer on urban affairs and the founder of Telestrian, a data analysis and mapping tool. He writes at The Urbanophile.

Lead Photo: São Paulo City by Julio Boaro

Crucial factor: land rent and the supply of land for housing

I have spotted this essay a bit late. I think the "turning the corner" process you describe, regarding "....perpetual entrenched poverty, poor infrastructure and public services, and low quality of life by global standards....." is heavily dependent on one significant factor.

This is the minimisation of economic land rent.

Every city that has "developed" and improved housing conditions and spread home ownership in the formal housing market, has had a paradigm shift in economic land rent, which is due to competitive automobile based development being allowed. This brings super-abundant quantities of low cost rural land into "supply" for the urban economy for the first time, and collapses land rent per square foot in the entire urban area.

The predominant paradigm that leaves half the population permanently "priced out" of the formal housing market, is because rising incomes capitalise into urban land rents at a rate that is always ahead of the ability of those "unhoused" to catch up. A systemic collapse of urban land rent breaks this impasse.

Think about this - it is the facts.

It does not surprise me that Tokyo has been so slow to democratise decent housing conditions; and that this has only finally occurred once they had a systemic crash in urban land prices. Without this, the fact that improving local amenity capitalises into land rents, always leaves the lowest income earners priced out of the amenity-provided locations.

I would also argue that conditions for the lowest income earners in London and other UK cities has been converging on third world cities because of the Town and Country Planning system's enabling of the capture of increased land rent, in contrast to the decreasing land rent that typifies most first world cities - until growth containment "planning" restores the rentiers to their "rightful" historical place.

Developing countries that maintain the rentier classes power through planning and/or outright corruption, will never solve the problems that the above article correctly identifies. The solution, unpalatable to the modern anti-sprawl advocates, IS "sprawl".