This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism called "America's Housing Crisis." The report contains several essays about the future of housing from various perspectives. Follow this link to download the full report (pdf).

When I was in college the suburbs were vilified. It was the mid-2000s, and here we were, enlightened coeds having one last hurrah in the flat Midwestern expanse before finding our place in the world, and there really was only one world to find: the city.

A lot was fueling this. Some of us were reacting to Walmart childhoods, the big box strip malls a symbol for all that embarrassed us about America – corporate consumerism, excess materiality, a primacy on efficiency over heart. Others found in urban contrasts a call to heal social divides. But whether motivated by altruism or hipsterdom, the city seemed like the only place to live a meaningful, “authentic” existence. We were taught that the suburbs were vanilla, bland, buffers for Boomers to hibernate with their own kind. Cities, by contrast, offered risk, adventure, diversity and grit.

Fast-forward a decade, and these differences have faded and even reversed. Sure, cities in the mold of New York, San Francisco, Chicago and Los Angeles still appeal to the young and mobile. But, lately, as housing prices in the most appealing urban cores skyrocket across the country, metropolitan centers find their middle class aspirants fleeing for greener and less expensive pastures.

Today, many suburbs are remaking themselves as formidable incubators for social mobility and globalism, their sprawl punctuated by street signs in other languages, strips of ethnic eateries, self- confident civic innovation and a fresh aura of hope.

This suburban blossoming represents an underreported shift in settlement

patterns of our new immigrants and minorities. Where “To the city! To the city!” was the unquestioned mantra of newcomers landing on Ellis Island in the first wave of mass migration between 1880 and 1924, today’s Latin Americans, Asians, Africans and African Americans are voting with their feet in a new direction. “To the suburb!” – if it didn’t sound like a minivan’s whimper – would be the banner of the day.

SOME FACTS

It would take a hermit lifestyle not to notice the demographic sea change that’s swept the United States over the last three decades. European immigration, once the mainstay of growth for the U.S., fell 32 percent, even amidst the continent’s hard times, from 2010 to 2013. In 1980, Mexicans accounted for the most populous group of foreign-born at 2.2 million, followed by Germans at 849,000. By 2010, the Mexican population had more than quintupled while European immigrants had fallen from being 36.6 percent of the total foreign- born population in 1980 to 12.1 percent in 2010. Mainland China now follows Mexico at 2.2 million, with Indians and Filipinos close behind at 1.8 million each. Today, the sending regions with the largest numerical increases in the number of immigrants living in the United States since 2010 are East Asia (up 642,000), South Asia (up 594,000), Sub-Saharan Africa (up 282,000), the Middle East (up 277,000), the Caribbean (up 269,000), and Central America (up 268,000).

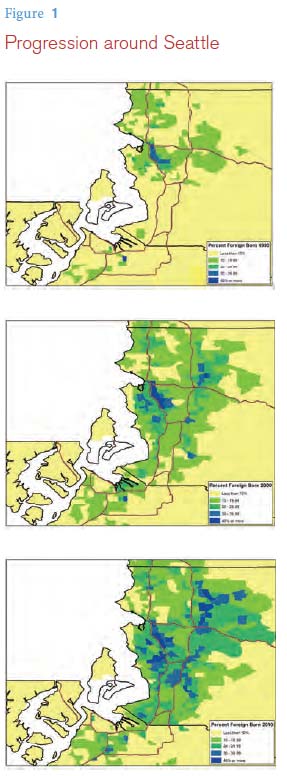

The swell of these “new immigrants” has revived perennial American questions around national identity that ever undergird our migration policy debates. The issues touch almost every region, with suburbs and smaller cities in the country’s interior feeling them most acutely. Where Los Angeles, New York City and Chicago were once the obvious gateways to build an American life, now the cities in the South and West are increasingly attracting the foreign-born. Since 2000, 76 percent of the growth in the immigrant population has occurred in these smaller metropolises, with Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, Oklahoma City and Columbus growing the fastest. A related trend is that as of 2007, four in 10 immigrants now move directly from overseas to the suburbs, eclipsing the urban experience that had always been the landing pad.

The Brookings Institution came out with an important report last year detailing these shifts. In 2000, more than half of the nation’s immigrants lived in the suburbs of our largest metros. According to census data from 2000-2013, that number is now up to 61 percent.

More than a third of the 13.3 million new suburbanites between 2000 and 2010 were Hispanic, with whites accounting for a mere fifth of suburban growth in that same period. Between 2000 and 2012, the Asian population in suburban areas of the nation’s 52 biggest metro areas grew 66.2 percent, while that in the core cities grew only by 34.9 percent. African Americans have also been steadily moving from inner cities to the suburbs. The 2010 Census showed that each one of the nation’s 20 largest metro areas saw a significant decrease in their proportion of black residents, with African Americans as a group shrinking from 65 percent urban in 2000 to 49 percent in 2010.

The regional details are even more striking. Since 2000, the suburban immigrant population has doubled in 20 metro areas. In 53 metro areas, the suburbs accounted for more than half of immigrant growth, including nine metros in which all of the immigrant growth occurred on the periphery: Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Grand Rapids, Jackson, Los Angeles, Ogden, Rochester, and Salt Lake City. Atlanta and Seattle, long skirted by immigrants and even now ranking outside the top 10 largest immigrant destinations, each added more immigrants to their populations than did Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, or Los Angeles. Crucially, since 2000, not one metro area has seen its foreign-born population in the suburbs decrease.

What this means is that the suburbs as a whole are now equally, if not more diverse, than the populations living in most urban cores. They also are generally less ethnically segregated. Go to a Starbucks in Sugar Land, Texas, and you’re more likely to stand in a line resembling the United Nations than anything you’d find in the center of Manhattan. Same goes for Fairfax, Virginia, where the demographics far out-pixelate Washington, D.C. 29.5 percent of Fairfax residents are foreign born, compared to 13 percent in D.C. 16.4 percent of Fairfax’s residents are also of Hispanic origin and 19.2 percent are Asian, compared to only 10.4 percent Hispanic and 4 percent Asian in D.C.ix Irving City and Carrollton just outside Dallas see their foreign born comprising 35 and 28 percent of their residents, respectively, while Dallas proper caps at only 23 percent. In Washington State, 34 percent of Bellevue is foreign born, while Seattle’s foreign born stands at a mere 17.7 percent.

It’s important to note that this movement to the periphery does follow overall population settlement patterns observed since 2000 – it is not simply an immigrant or minority phenomenon. As elite urban hubs suffer from high housing prices, experiencing then a widening chasm between the very rich and the very poor, the suburbs have become a harbor for the middle class to find more reliable footing. And while my suburban-raised college classmates and I turned our noses up at their presumed provinciality, an Aspen/Atlantic poll from three months ago showed that most Americans still consider a family-oriented, suburban neighborhood closest to their “ideal” in terms of where to live, with 53 percent of whites, 53 percent of African Americans, 53 percent of Hispanics and 63 percent of Asians aspiring to this future.

Recognizing that immigrant and minority migration patterns mirror shifts undergone by the population at large, there remains a texture to the suburban shift specific to both the contexts and the aspirations of today’s immigrant and minority groups, a texture laden with distinct promises and challenges as many pioneer lives on a more sprawling landscape. Here is a closer look at why the New America is suburbanizing, and what this may bode for the future.

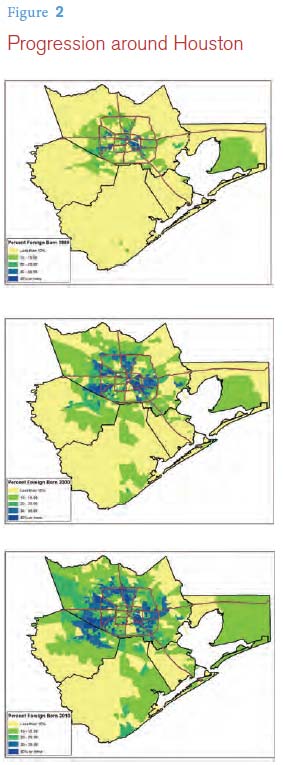

THE CASE OF HOUSTON

Take a drive westward from almost any major airport today and you’ll see these worlds unfurling. In Houston, now the most ethnically diverse metropolitan area in the country, its white population is increasingly concentrated inside the inner loop (particularly millennial singletons) with everyone else settling beyond. As of 2013, over half of the city’s immigrant population—56 percent—live in Houston’s suburban municipalities, with 80 percent of the growth of the area’s foreign-born population since 2000 occurring in the suburbs.

This diversity shapes how I live. One recent Sunday, after waking up at 6:30 AM for a game of tennis with some Vietnamese friends who’d trekked in to Houston’s inner loop from Sugar Land, I found myself traveling the world in a zip code. The court transitioned to church at an all-black Methodist congregation 32 minutes from Houston’s downtown, followed by a Peruvian brunch at a rotisserie chicken eatery sitting just across the street from a large Indo-Pakistani shopping plaza. I then wandered over to the neighboring Hispanic mall known as PlazAmericas before taking a right on Bellaire Boulevard to peruse flavors of shaved ice at Chinatown’s Dun Huang Plaza and sampling Korean pears at the pristine Super H, with Latino shelf-stockers backing the Korean cashiers. Café Beignets, a Vietnamese interpretation of New Orleans charm, nourished with fried dough in the middle of a “Saigon Houston Plaza” that seemed to take its aesthetic cues from Pottery Barn, Asian-accented. All manner of sacred architecture beckoned from behind the strip malls, with the Buddhist Teo Chew Temple peeking out from beneath the tree tops and a dozen Spanish and African-speaking church signs within view around the corner.

This was all a suburban version of “verges” – the vortexes where civilizations clash and conceive a fresh dynamism. Only in this case it wasn’t Istanbul; it was the Beltway crossing route 59.

Houston rightly carries a reputation as one of the most welcoming cities in the U.S. While cultural traditions from elsewhere are invited to express themselves, the first question most Houstonians ask is not, “Where are you from?” but “Where are you headed?” The environment is future-oriented, open and adaptable. Buildings are torn down one month and rebuilt the next. There’s something for everyone, and the more outsiders come for jobs and the hope to establish a stable and happy life, the more Houston is texturizing to reflect the values and needs of the globe within it.

“I think Houston offers people an opportunity to entrench themselves,” says John Tran, a second-generation Vietnamese lawyer in his mid-thirties, living in Sugar Land, also the town of his childhood. “It’s one of those places that gives people time to assimilate at the same time that it also gives them time to develop their own identity.”

The sprawl invites a tension to play out between tradition and innovation, stability and risk.

“The message is: Do it your own pace, do it your way, you have a home here,” Tran says.

This is a great opportunity as well for the realtors and homebuilders as they reinvent the sprawling landscape to suit the aesthetic tastes of their diversifying clientele. Local architect Tim Cisneros is currently working on a $10 million dollar Indian wedding facility in Sugar Land that will be capped by a helipad and bridge built to withstand an elephant’s weight for the groom’s entrance. Cisneros serves some of Houston’s most entrepreneurial immigrants, his portfolio including a Chinese museum of history and culture (“Forbidden Gardens”), multiple Indian restaurants and a Messianic Jewish worship center.

Each project involves an anthropological education. Cisneros recalls:

“When I was in the running to design a Daoist temple, I had to go to this ritual. They’d put the various names of the architect candidates into a calligraphic gold pot with sparks and smoke. My job depended on whether some karma favored my name.”

Cisneros now calls Houston his “favorite third world city,” hinting both at its development potential and the ambience that appeals to today’s new immigrants. From the tropical climate, to the zone-free real estate possibilities, to the hodge-podge aesthetic that disorients and welcomes anyone looking to make a mark, there’s both a familiarity to those coming from the developing world but also a chance to enjoy greater personal space than they were allowed in cities like Seoul, Abuja or Delhi.

“The immigrants we work with,” says

Cisneros, “they think they’ve died and gone to heaven. They don’t get caught up in the fact that their father’s generation wasn’t born here.” There’s opportunity, and perhaps more importantly, a sense of limitless sky.

THE PERCEPTION OF MORE CHOICE AND OPPORTUNITY

For most of U.S. history, immigrants have been concentrated in iconic cities. Early waves of European immigrants initially moved into neighborhoods close to the factories and shops that employed them. Go to Manhattan’s lower east side and you’ll still catch a whiff of the German, Irish and Jewish flavor that defined this neighborhood at the turn of the 20th century. As increasing numbers of immigrants have flocked to the suburbs at the turn of this century, however, it’s clear the new immigrants are reshaping the geography of opportunity.

To dig into this, I’ve spent the last few months interviewing national migration experts and district school superintendents, exploring the growing array of suburban social services and attending a wide variety of religious services and cultural celebrations in the most diverse county in the nation—Fort Bend, just west of Houston. What’s come to the surface, amidst all the variance in regional patterns of settlement, is the issue of agency. Choice, or lack thereof, is the fault line in the nationwide trend toward suburban living. Some move because they can and choose to – the suburbs have attractive features worth pursuing. Others are forced out as they’re displaced by gentrification, changes in local labor demand, and, sometimes, black-white racial tensions.

“You’ve got two streams of immigrants flowing out of the urban core,” says Stephen Klineberg, founder of the Houston-based Kinder Institute. “One contains the engineers, doctors and information technology professionals, many of whom are Asians and Africans that enter this country with higher educational levels than many native- born Anglos, and the other contains the poor and uneducated, most of whom are black and Hispanic. Where the upper middle class of Asians and Africans tend to go where the property values are higher, where the schools are good and the jobs plentiful, [poor] blacks and Hispanics are increasingly being clustered in low-cost areas, getting pushed farther and farther out.”

These ethnic delineations may be too sweeping --- there are many upper income Mexicans and Africans, for example --- but Randy Capps of the Migration Policy Institute at least agrees on the pattern. “Your distressed communities are going to attract people who have no choice,” he says. “The poorest people are going to be increasingly transient, namely, poor blacks and Hispanics.”

For those with the capacity to move of their own accord, choice itself explains the reasons for the suburban move. Behind the practical appeal of lower housing prices, more jobs and better schools, every immigrant I interviewed alluded to the air of untapped possibilities that they no longer sensed in dense urban cores. The growing magnetism of a city like Houston, for instance, along with other suburban cities in the South and West, is in part rooted in the sense that you don’t have to be a part of the establishment to move up. Social mobility is possible for those with the wherewithal to climb.

“The American Dream is alive and well here,” said one restaurant owner. “If you want to make it, you can. I haven’t been able to find that possibility in other cities.” Other suburban dwellers agreed. “Urban density doesn’t grant easy permission for the imagination,” said a Vietnamese couple. “Suburban landscapes at least invite you to try to make your own mark.”

THE IMPORTANCE OF HOME OWNERSHIP

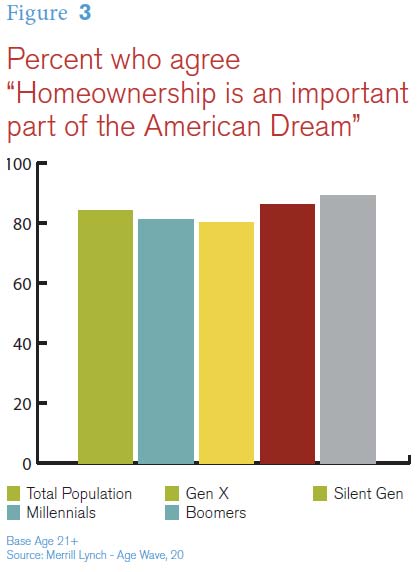

If more space and choice lie at the core of most minorities’ hopes, buying a home seems the first logical step to securing them. For immigrants in particular, transitioning from renter to homeowner is an important milestone in committing to the United States. The question is: Where is this transition now possible? And are immigrants and minorities more willing to take the leap into far-flung coordinates because owning a home is more critical to their civic credibility than it is for today’s average native citizen?

There’s some data to suggest that in a society increasingly accepting of a “rentership” mentality, immigrants remain more likely to strain for permanence. The national homeownership rate has been declining for ten consecutive years.xii You see this pronounced especially amongst the young. Those in the prime of their adulthood, between 35 to 44 years of age, are buying homes at a low rate not seen since the 1960s. And for minorities, the numbers dip lower – the gap between white and minority home ownership is 25.5 percentage points.

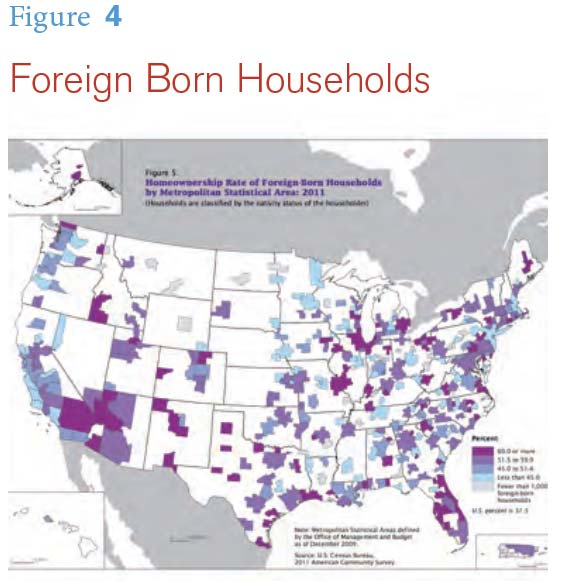

However, when you look at the maps detailing migrations of minorities and immigrants, and where they tend to be growing, they are growing fastest in places where houses are being bought. According to a report by the Research Institute for Housing America, immigrants accounted for nearly 40 percent of the net growth in homeowners between 2000 and 2010; in the 1970s they represented just over 5 percent of the growth. Meanwhile, the foreign born have been moving towards ownership, with renting growth happening only in the states that have become tough for prospective homeowners – e.g. California, the Washington D.C. area, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Illinois.xiv In the current decade, California and New York are projected to be the only two states where foreign-born homeowner growth declines. Texas and Florida, by contrast, are attracting foreign- born buyers in droves, with net increases of 492,000 and 342,000 projected.

As Hispanic and Asian homeownership in particular is climbing, they’re buying in the second-ring suburbs and even exurbs where they are settling in large numbers. We can see this by looking at maps of several major metropolitan areas such as San Francisco, New York, and Chicago.

Obviously, when home ownership is the top priority, where it can be affordably attained becomes all the more relevant. Aspiring homeowners tend to want to live around other homeowners – there’s a like-attracts-like buzz of “I want to be around other people who are making it.” Minorities also seem to be maintaining the more traditional American idea that homeownership equals the final seal of adulthood.

“Buying a house was important,” says Tran, the 35-year old lawyer who lives with his wife in Sugar Land, a town in Fort Bend County. “It was roots being planted, physically and emotionally. If marriage was the emotional commitment, the house was the physical aspect of that.”

The Trans’ neighbors, an African American couple named Geoff and Robin Boykin, agree.

“As a minority, owning a home gives you a level of credibility in the community that renting won’t,” Boykin says. “When we first moved to this neighborhood, we rented, just to be sure, and when people would come up and ask us about it, there was an underlying feeling of embarrassment. Like we were second-class citizens. Perhaps especially because we’re the only black couple in this neighborhood.”

Geoff grew up in Brooklyn, New York, “where you don’t even think about buying.” But when he met a 24-year old who owned a house in Houston, he thought, “Wait a second. Where can you buy a house at age 24?” He moved to Texas to follow suit. Southwestern sprawl offered an opportunity to get established, cheaper.

Suburbs have always been family- friendly, at least by brand, and as Caucasian family size continues to shrink, those Hispanic and African American still having children, even three to four, kids want to be in safer, more affordable family-oriented neighborhoods.

“You are now more likely to have inter-generational communities in the suburbs,” says Randy Capps of the Migration Policy Institute.

Tim Cisneros, the architect who serves some of Houston’s most entrepreneurial immigrants, says that his clients typically want something “colonial or traditional, to show they’ve assimilated. They also want big, to host multi-families.”

"It’s now the Indians and wealthy Mexicans building the McMansions in the exurbs,” says Cisneros. “In Sugar Land. Pearland. The Woodlands [just north of Houston] is like going to private

Mexico now. With armies, guards, the whole nine yards of the Mexican elite.”

If homeownership remains one of the more important seals of legitimacy for

today’s immigrants and minorities, it’s also a tool for consumer status – in this case one’s civic and cultural status.

“With many immigrants,” Cisneros says, “the shinier it is, the more expensive they assume it to be and thus more attractive. More ’making it’ in America.”

On the other side of the real estate spectrum, of course, are those who are getting priced out of longstanding ethnic enclaves that lie closer to the city center. Ron Castro is a sociology and psychology teacher at Spring Woods High School in Spring Branch, a gentrifying suburb straddling Houston’s second freeway loop, and says that in 15 years of teaching, house prices have climbed from $90,000 to $400-500,000.

“Folks I used to know can’t afford to live here anymore,” he says. “Everyone’s saying, ’we’ll be on our way out pretty soon.’”

“In ten years, these mini-mansions pop up. The neighbor can’t afford that. I don’t see how low-income people survive another 10 to 15 years here in Spring Branch.”

JOBS, SCHOOLS AND AN ECONOMY AGING BACKWARDS

Most of today’s middle class economy is now found outside of central downtowns. Suburbs and exurbs accounted for 80 percent of job growth between 2010 and 2013.

Irvine and Santa Clara in California, Bellevue just outside Seattle, and Irving, a Dallas suburb, have higher job to resident worker ratios than their closest core municipality. The booming technology sector is adding most of its jobs to suburbanized areas like Raleigh-Durham, Dallas-Ft. Worth and Orange County, attracting high-skilled Indian and East

Asian employees, in particular.

And, as “live, work, play” locations proliferate, it isn’t just a matter of where the jobs are located, but also where the highest quality of integrated living – work + leisure + community – may be found.

“Sugar Land’s Town Center has everything you need,” says Geoff Boykin, who works for Coca Cola two miles from his home. “All the amenities – restaurants, Home Depot, a movie theater, the gym – I love the convenience.”

At the same time, many suburbs are developing multi-purpose complexes of community and leisure that complement their growing professional class, while telecommuting is on the rise, especially amongst millennials. For younger minorities and adult children of immigrants, commuting to work is no longer a must. So long as a suburb is relatively close to a freeway entrance, other desires like strong recreational possibilities and a good night life can take the front seat. The Internet has lessened the need for many to weigh the variable of long commutes.

Rental properties for small businesses – many of which are owned and run by immigrants – are almost universally cheaper in the suburbs. And as more and more millennials are moving to the suburbs, businesses are noticing the outflow of their consumption habits.

“My clientele here is getting older, less willing to spend,” says Yoichi “Yogi” Ueno, the owner of a Japanese Sushi restaurant in Rice Village inside Houston’s inner loop. A few years ago he decided to open another more casual location in Fort Bend County on Bellaire Boulevard, in part to attract the freer flow of youthful wallets.

“The well-educated, higher income younger people are having kids and moving out to exploding suburbs like Sugar Land and Katy,” Ueno says. “They now have more vibrancy. I may move this restaurant out there one day. I think business may be better.”

For those with kids, of course, the historic sense that the suburbs have better schools and safer streets remains true, and of acute appeal to those looking to give their offspring a secure and promising future. There’s also more educational choice in the suburbs, and with lower costs of living, the possibility to send one’s child to a private school becomes easier.

“For many Asian families in particular,” says a Vietnamese couple with one middle schooler and two elementary-age sons, “living where the schools are ’good’ becomes the number one priority.”

THE PRE-EXISTING CULTURAL CLIMATE

The movement of immigrants to the suburbs draws more to the same places. Just as immigrants in the first wave of mass migration went where families had already set up house and shop, today’s suburbanizing immigrants report a stronger sense of belonging and feeling welcomed in the suburbs, compared with urban cores too entrenched in established legacies and racial histories to leave room for more. There is also more of a chance for coherence and authenticity in immigrant expression in the suburbs, manifested most obviously in ethnic restaurants and supermarkets, distinctive religious congregations and social networks.

“In the suburbs, I can run a sushi restaurant more like they do in Japan,” says Yoichi Ueno. “Here, closer to the city, with more of an affluent and white clientele, I had to invite in a chef to introduce things like California rolls [to appease American tastes]. In Japan we don’t actually sell those rolls!”

These commercial enclaves are attractive in both entrepreneurs and their customers.

“I like being in a Latina neighborhood,” says high school teacher Ron Castro, who’s chosen to stay in what some consider a less desirable suburb outside the loop. “There’s a Fiesta out here. A carniceria.”

There are also scads of religious communities in the suburbs, the spires of sacred structures peeping just behind the strip malls. With secularism predominant in elite urban hubs, faiths from all over the world are finding welcome and freedom of expression in the wide open spaces where immigrants and minorities are settling. Religion remains a central artery for those beginning new lives, providing a sense of ethnic identity and continuity, social services and social status.

SOME BROADER OBSERVATIONS ABOUT TODAY’S SUBURBAN ECOLOGY

As I’ve wandered through and sampled the flavors of various suburban communities in Houston and elsewhere (including Charlotte, Dallas, northern Virginia and Chicagoland), it is clear there is a more textured political climate developing there. Most minority suburban dwellers I spoke with sounded progressive on immigration and the role of government in providing social services, and conservative on business regulation. The flourishing of the family was clearly important, even in its traditional expression, but those interviewed skirted any political commentary on that front.

The suburbs also appear to be eclipsing the city as centers for civic renewal and volunteerism, though more empirical study of this is needed. Every suburban resident I interviewed was involved in at least one local initiative, such as Moms against Drunk Driving, seasonal clean-up effort and local arts & craft festivals. This stands in stark contrast to the average single professional renting a loft downtown, most of whom are involved in loose social diasporas but otherwise see the city as a one-way consumption opportunity.

Some of this may have to do with life stage, and the higher proportion of families in suburbs—the attendant reality being that kids naturally invite parental involvement in the milieu of their upbringings. But the sense of voluntary generosity is also a testament to the growing presence (and confidence) of immigrants in the suburbs, who show higher rates of volunteering both inside their ethnic networks and, with growing levels of affluence, beyond them.

Finally, the influx of immigrants demonstrates how suburbs are where a strong sense of community can be built and sustained. I repeatedly noticed how rare I was as a single car-user in parking lots that otherwise saw piles of kids tickling each other in the back seat – particularly the case for lower to middle class Hispanic and African American neighborhoods. In a Peruvian restaurant in Fort Bend on a Sunday afternoon, I was the lone millennial eating lunch solo and scrolling through my iPhone, the other tables raucous with the laughter of children and grandfathers in church attire. It struck me that the suburbs, with all of their automobile dependence, remains a relative bastion of strong community feeling and sense of obligation. Contrary to the general academic and media portrayal of suburbs as hotbeds of alienation and anomie, they are becoming bastions against the seduction of a consumerist, individual autonomy.

COMPLEXITIES AND CHALLENGES

As stated at the outset, it is in many ways impossible to speak about “the suburbs” in a generic sense. There remain two streams of movement outward: one rooted in choice and the other in forced displacement. But there also remain important caveats to these selling points, caveats that illuminate the open questions around the future of suburban life and human flourishing within it. The first is the challenge of isolation and integration, especially as the suburbs continue pixelating in ethnic and cultural diversity.

Houston, for instance, is a city that welcomes the stranger, but its layout is sprawling, enticing for those with gumption can prove intimidating for those torn from their native support structures (or lacking them in the first place). Social services slim down the further you get from the Beltway. Public transportation is sparse, and sustaining driver’s licenses can be tricky for the undocumented. Information is under-institutionalized and rife for predatory activity – immigration lawyers and mortgage brokers, both. For those with few resources, life can be a constant struggle.

Public schools feel the brunt of these rapid demographic shifts, with diversifying student populations outpacing the cultural training of teachers. H.D. Chambers is the superintendent of the most diverse district in Texas – Alief – and he says the avalanche of students coming from economically disadvantaged backgrounds (800 new Burmese refugees amongst them), combined with those coming with little to no English knowledge, make providing a strong educational experience profoundly difficult.

“I’m talking about diversity that’s deeper than color of skin,” Chambers says. “It’s about diversity of life experiences, and what these kids face when they go home. Many of their parents can’t help them. How do we teach them to interact with others? How

do you prepare these sorts of kids for a global economy and the world at large?”

Not all immigrants – particularly the children of the foreign born – appreciate the suburban edition of the American Dream their parents foisted upon their upbringings.

Raj Mankad is the editor of an architecture magazine housed at Rice University, and as a child emigrated from India to a cul de sac in Mobile, Alabama. Years later, as an adult, he asked his parents why they opted for the spacious suburbs after the chaotic yet cozy density of living in India. They answered in classic 1.0 form: As an immigrant, you want to go for the opposite of what you left behind.

“We arrived with five dollars in our pockets,” they told him. “We could not buy expensive things or houses in the best neighborhoods. And we grew up with very little, sharing bedrooms with all our siblings, sleeping on the floor, walking to school without shoes. So when we arrived in the United States, we wanted exactly the opposite.”

Raj has since rejected a lifestyle he finds plastic for a hipper, culturally creative and environmentally conscious life with his Caucasian wife and two young kids in Houston’s Montrose corridor. He rides a bike to work and aspires to start his own spiritual community inside the loop.

“I want my kids to understand their Hindu heritage, but the temples are in the suburbs, and I don’t want to schlep out an hour for a religious service. I want to start my own spiritual community, but not in a conservative way.”

The price may be high compared to what his Indian American peers are choosing on the periphery, but it’s his preferred assimilation – honest, expensive, and full of uncomfortable tensions.