Ben Bernanke made the following statement as he attempted to justify bailing out bad borrowers:

“…from a policy point of view, the large amount of foreclosures are detrimental not just to the borrower and lender but to the broader system. In many of these situations we have to trade off the moral hazard issue against the greater good.” – Ben Bernanke, February 25, 2009

I think he is wrong on this, and the moral hazard issue is only a small part of my objections.

One of the fundamental problems we have right now is that too many people own homes. It sounds harsh, but please bear with me a few sentences. I think we can agree that 100 percent home ownership is not possible, or even desirable. Most of us can remember a time when our income and our jobs were such that home ownership was a bad idea. Home ownership is a commitment that requires a significant amount of stability and discipline. Not everyone is so stable or has the discipline to keep up with the payments.

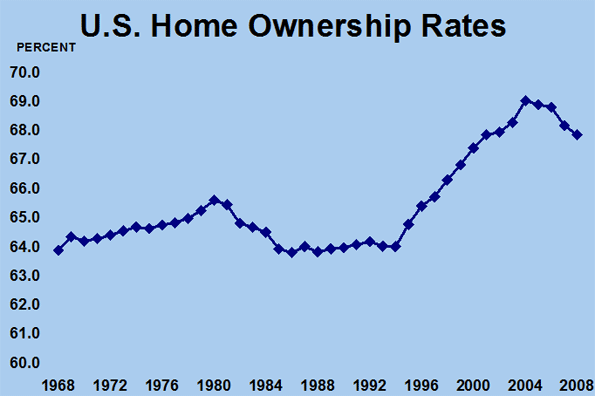

What is an appropriate national homeownership rate? Theory gives us no answer. We look to the data for a clue. Here’s a chart of home ownership rates since 1968:

It seems pretty clear that a homeownership rate between 63 percent and 65 percent works pretty well. When we get above that range, problems seem to crop up. This was true in 1980 – the worst recession of the past 30 years – and it is true now.

In light of these data, let’s think about what Bernanke is saying. He’s arguing that to execute the foreclosures required to move the rate back to that 63 percent to 65 percent range are bad for the economy. So bad in fact, that we’re better off not going there.

The problem with that argument lies in a lack of historic understanding of the proper levels of homeownership. Financial and real estate markets can’t stabilize until we get closer to that equilibrium. Until we lower the home ownership rate, financial institutions will have a cloud around them, and residential real estate markets will be lifeless. It may not be politically popular, but those are the realities.

This is a critical issue. For years, economists have believed that the failure of banks to recognize and remove bad assets contributed to Japan’s long period of economic malaise. I agree. Forbearance on bad real estate loans here in the states constitutes much the same thing. Our financial institutions are holding a bunch of bad assets; these are homes that are owned by people who can not afford them – never did, and likely never will. Until the financial institutions recognize those bad assets and get them off their books, our financial institutions won’t have the resources to fund, stabilize and then drive a broader economic recovery.

What we need is not more mindless beneficence to everyone from Wall Street to Detroit and Main Street. The more we bailout failed financial institutions, automobile manufactures, or any business, the longer we postpone our recovery.

Recessions are periods when assets are reallocated from less productive to more productive uses. That requires processes like repossession, foreclosure, mergers, and bankruptcy. These processes have been developed over centuries. They are the most efficient methods to restore an economy.

Why are we suddenly abandoning these processes that have proved themselves in many business cycles? I suppose part of it is the desire to eliminate the business cycle. This is the same thinking that had many – including conservatives – arguing that stocks could not fall during the dot.com bubble or that housing prices would also move up.

In reality the business cycle can not be eliminated. It can’t be done and it is pure hubris to try. One of the fundamental insights to come out of Real Business Cycle research is that recessions constitute the most efficient response to a negative shock.

We need to stop wasting resources trying to stem the tide. Instead, let us allow the recession to work for us. In the meantime we can provide a backstop through unemployment benefits and some reasonable fiscal stimulus. But we have to experience some pain and let our processes and institutions work for us. The sooner we get these foreclosures, repossessions, mergers, and bankruptcies behind us, the sooner we will see a return to the only sure cure for a sick economy: real economic growth.

Bill Watkins, Ph.D. is the Executive Director of the Economic Forecast Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is also a former economist at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington D.C. in the Monetary Affairs Division.

Does everyone in America

Does everyone in America really need to live in their own home? Many would be better off living in an apartment. Homes incur significant transactions costs when one moves. Homes also require more time commitment from the owner. In our increasingly mobile society in which white collar employees are putting in more hours not less, one would think that home ownership would be falling, not rising. Of course people who owned homes during the last few years are a lot better off financially because of it; but that’s a lucky historical anomaly that may end in tears for the last owners to jump on the bandwagon. Meanwhile, Federal Reserve made low-interest loans for banks. It turned out that the Congress and the shareholders were not aware of the short term loans worth at least $100 billion which were made by the Federal Reserve to banks during the financial crisis of 2008.

Home is a lifetime

Home is a lifetime investment so government must have to put additional fund on home ownership.Anyway,Turner Radio Network isn't affiliated with Ted Turner; rather, it is run by Hal Turner, a white supremacist who likes to claim a libertarian mantle. His radio show and blog have leaked the incomplete stress tests, and the results point out the largest banks in the U.S., those that received the lion's share of bailout personal loans from the taxpayers, are all heavily leveraged, and are in danger of insolvency. Regardless of the questionability of the source, large banks would doubtless like to repair credit after the Turner Radio Network leak.

Ownership for the sake of...what?

Bill Watkins is basically right: many people got mortgages who had no business getting them. Why? Banks seemed suddenly eager to lend money to people. Remember George Bush expressing his desire for the US to become an "ownership society?" And then, when it all crashed down, they quickly blamed previous policies that encouraged expansion of home ownership.

Owning a home comes with great responsibility, and it isn't for everyone. Whether the true rate is 63% more or less, or in fact might be lower (In Europe I suspect it is far less, and in third-world countries probably even less), will get sorted out.

For those gullible enough to get talked into wierd terms, or 2, 3, 4, or more mortgages thinking it was a hip new way to invest, sorry; take your lumps. For those of who are struggling to hold on to one garden-variety mortgage, we shall see if our assets can be saved. Few got consideration in the 1930s.

My personal definition of expansion is when I reallocate my capital assets. A recession is when my capital assets get reallocated for me.

Richard Reep

Poolside Studios

Winter Park, FL

I'm not arguing that

I'm not arguing that expanding homeownership is always and everywhere a good thing. I would agree that in may cases it provided cover for the likes of Angelo Mozilo & the gang at Countrywide to continue their predatory lending racket. What I take issue with is how Mr. Watkins extends that point to argue that allowing the economy to sink into a deep recession is somehow the most "efficient" thing to do. What really galls me though is how he says "we" deserve to feel some pain, as if Mr. Watkins himself will be adversely affected by any of this. He will likely retain his cushy job, which apparently consists of telling the little people that they deserve to lose theirs. That's pretty rich, no?

@ EPAR:

@ EPAR:

You've committed a number of errors of reasoning-fallacies-in your comments here. Let's start with the most recent:

1) "What really galls me though is how he says "we" deserve to feel some pain, as if Mr. Watkins himself will be adversely affected by any of this. He will likely retain his cushy job, which apparently consists of telling the little people that they deserve to lose theirs. That's pretty rich, no?"

Fallacy: Ad Hominem attack. A medical analogy would be the following: the thin, non-smoking doctor is advocating that I reduce my dietary fat and stop smoking to reduce weight and my chances of developing heart disease. Therefore, since he doesn't have to take his own advice, it's mean of him, or 'rich' in irony.

2) "Your view is not an innovation of Real Business Cycle theory. In fact it has been propounded by the likes of Karl Marx, Hoover and his treasury secretary Andrew Mellon, the British exchequer during the Depression, and Friedrick Hayek. But it was dead and buried by the time Milton Friedman disparaged it in the '70s, and continues to carry very little weight among modern economists across the spectrum. Just something for readers to keep in mind before they conclude that the best thing to do is let the banks fail, liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, and liquidate real estate."

Fallacy: Appeal to Authority. What 'modern economists', i.e., Keynsians, Monetarists, and the like, whom you agree with, believe, has no necessary connection to the truth. It was 'dead and buried' only in your view, not for any legitimate reasons.

---------------------------------------------------------------

So what reasons have you actually given?

a) "But we didn't have a recession during the ramp up phase of the tech boom or the housing bubble, when lots of labor and capital were allocated from other industries to the tech and construction industry, respectively."

No, since in any boom that is big enough to carry the whole economy there are enough jobs created, i.e., labor is in high enough demand, 'in the ramp-up phase' to make the re-allocation pain-free. This proves nothing about whether in the long-term the projects and capital investments for which this labor is being re-deployed will be sustainable. If, according to Austrian business cycle theory (also long 'dead and buried'), those malinvestments are not sustainable in the long-term, then, to use a no doubt Stalinistic phrase, they 'need to be liquidated'.

b) "Furthermore, during recessions, we observe that unemployment increases across all sectors, not just the ones that were bloated as a result of a speculative bubble."

Of course unemployment increases in all sectors because all sectors had been stimulated, more or less, to some degree, by the Fed low interest rates and by the spread of easy housing money throughout the whole economy. The economy is not a ship with watertight bunkers sealing every compartment, but an interdependent system where capital flows from one to another.

c) "So recessions may be more complicated, and not as amenable to a moralistic "we must suffer for past excesses" mentality as you would like."

Well, there are a moral and economic components to most economic problems. And both recent administrations have given lip service to this truth with their mention of the dangers of 'moral hazards'. Any government interference that goes beyond laissez-faire violates the rights of someone, and therefore is not only an interference in the efficiency of the markets but an injustice as well. Metaphysically elegant it is that the immoral is the impractical. If, however, you mean that hundreds of millions if not billions of innocent people will suffer because of the inflationary economy that Alan Greenspan, the directors of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, Barney Frank, Chris Dodd and others helped create, then I wholeheartedly agree.

d) "But it is not clear to me why bad investments made yesterday should force perfectly good labor to sit idle today. If the problem is lack of effective demand for that idle labor, then government can create demand through fiscal stimulus or increase the cost of holding cash balances, thereby encouraging spending, through inflation."

The answer is clear to many of 'dead and buried' economists of the Austrian and classical schools. For example, central banks, by artificially lowering interest rates, fool investors and entrepreneurs during the 'ramp-up phase' into thinking that more money is available for savings and investment than it is. During the subsequent depression, those with capital naturally sit on the sidelines to wait for prices to accurately again reflect the economic realities that the Fed, the central bank, had distorted.

Government can create demand? You mean: central planning can work? Our own American Five Year Plan? Sure, but will the demand thereby created be any more efficient in the long-term than the artificial demand that has ended in the utter catastrophe of this worldwide depression? Centuries of economic history and the theories of 'dead and buried' free-market economists give no reason to believe that governments have the slightest idea what is best to invest in. If they did, the Soviet Union wouldn't have collapsed and China wouldn't have significantly freed up its own economy. There's no substitute-economically or politically-for freedom.

Interesting how you

Interesting how you implicitly rely on the same appeals to authority - albeit different authorities - for your own arguments. Anyways, I won't point out your own fallacies and hyperboles, simply because it's not worth the time debating anyone who seeks metaphysical elegance in economic policy - just as it's not worth the time debating a Born Again over evolution. I'm just thankful that those sharing your philosophy are far from the reigns of power in Washington.

No, Epar, I gave many

No, Epar, I gave many well-known REASONS why your explanations won't work, and instead you've failed to respond to any of those reasons. (See a, b, c, and d above in my previous reply). 'Interesting' indeed. I'm sorry that you couldn't help educate me by 'pointing out my own fallacies'-no doubt with your wisdom you'd have much to teach. A missed opportunity for us both!

I duly note your expressions of gratitude that those who believe in socialism, statism, or various forms of governmental control of human beings and the economy, i.e., those people who have inhabited Washington off and on now for many decades, are still in power and their institutions still in place. The Fed, for example, was founded in 1913. I guess one Great Depression wasn't enough, eh? But surely the $65 trillion in total unfunded obligations, the present worldwide depression, and the coming collapse of the dollar are reasons for celebration! Long live Marx! And Keynes! Barney Frank and Chris Dodd! The socialist Obama and the deficit-spender Bush! Bernanke, Geithner, and Paulson! FDR, Clinton, Franklin Raines, and LBJ! Thank God for what they've wrought, and that they, or people who believe in them and their principles, are still in power!

The Andrew Mellon View

We need to stop wasting resources trying to stem the tide. Instead, let us allow the recession to work for us.

I guess that has a twisted logic to it, since the ~640,000 people who just filed for unemployment insurance last week won't be doing any work themselves...

Snark aside, I think your point about homeownership is well taken, but you approach the larger issue of recessions with the wrong intellectual framework, evidenced by this sentence:

Recessions are periods when assets are reallocated from less productive to more productive uses. That requires processes like repossession, foreclosure, mergers, and bankruptcy.

Capital and labor are re-allocated to different industries all the time. But we didn't have a recession during the ramp up phase of the tech boom or the housing bubble, when lots of labor and capital were allocated from other industries to the tech and construction industry, respectively. Furthermore, during recessions, we observe that unemployment increases across all sectors, not just the ones that were bloated as a result of a speculative bubble. So recessions may be more complicated, and not as amenable to a moralistic "we must suffer for past excesses" mentality as you would like.

Of course bad investments were made, investor losses were taken, and economic assets were deployed for endeavors that did not contribute to our productive capital stock - i.e. building homes in the Nevada desert. But it is not clear to me why bad investments made yesterday should force perfectly good labor to sit idle today. If the problem is lack of effective demand for that idle labor, then government can create demand through fiscal stimulus or increase the cost of holding cash balances, thereby encouraging spending, through inflation. Unfortunately our monetary policy option is tapped out, which leaves deficit spending as the only additional recourse. Curiously, you yourself come close to admitting this when you say we can provide... some reasonable fiscal stimulus. Please explain what you mean by "reasonable" - could it be a fiscal stimulus large enough to generate more effective demand, thus heading off a wage-price deflation that would prolong the recession? Or merely reasonable in the sense that it allows the government to create the illusion that it cares about the unemployed masses, while secretly knowing the truth that "we have to experience some pain"?

Your view is not an innovation of Real Business Cycle theory. In fact it has been propounded by the likes of Karl Marx, Hoover and his treasury secretary Andrew Mellon, the British exchequer during the Depression, and Friedrick Hayek. But it was dead and buried by the time Milton Friedman disparaged it in the '70s, and continues to carry very little weight among modern economists across the spectrum. Just something for readers to keep in mind before they conclude that the best thing to do is let the banks fail, liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, and liquidate real estate.

what do you think should be done short term and long term?

epar

What do you think should be done short term and long term?

Punishing people for saving money is a bad idea.

Inflation harms people who have saved money. Inflation harms retired people and others who are on fixed incomes.

The federal governments needs to do things that encourages businesses to create jobs. What do you think encourages businesses to create jobs? What do you think encourages people to spend money?

I hope you will consider commenting on my plan on http://www.newgeography.com/users/kenstremsky

Sincerely,

Ken Stremsky

Punishing people for saving

Punishing people for saving money may be a bad idea in normal times, but right now encouraging spending takes priority. Creating inflation expectations is precisely the way to do it.

Long term policy has to start with reforming the financial system. Reckless lending driven by financial innovations allowed Americans to substitute capital gains expectations for real savings.