The United States’ preeminence in science and technology has long played an underappreciated but vital role in ensuring U.S. economic and geopolitical leadership. But the United States risks squandering this precious asset today through neglect and misguided ideology.

After World War II, the country came to dominate global research and development (R&D) by building the best model for nation-scale innovation the world has ever seen. Before the war, the United States was, at best, a second-tier science power. The Manhattan Project, for example, relied heavily on expatriate European scientists. But between 1947 and 1950, the Truman Administration and Congress, in a series of decisions, adopted one of the most consequential policy objectives in history: to make the United States into the world’s unrivaled science superpower.

It worked for decades, but today the United States is losing ground in R&D. Stagnant federal investment, growing sclerosis within the country’s research system, and the decided turn at many leading universities against objective research and toward ideological activism are undermining America’s leading position in science and technology. It’s time to reverse each of these self-destructive trends. This means raising federal R&D investment as a share of the economy, reforming public universities (and hoping some of the leading private ones will follow), and insisting on renewed commitments to free inquiry and objective research as a condition for federal support for university research.

A winning model

The model the United States adopted after World War II – which drew from the landmark 1945 report Science – The Endless Frontier by Vannevar Bush, Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development – consisted of four components. First, Congress would fund most basic research at levels far above any other nation through agencies like the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NASA. Second, researchers at nonfederal universities and labs would do most of the front-line work, with federal grants awarded through merit-based peer review processes – with little interference from politicians or bureaucrats. Third, grantees could follow their work wherever the science led them, with no censorship from government or university authorities. And fourth, Congress created the world’s best environment for turning discoveries into world-changing products by not just allowing but encouraging innovators to claim patents over their inventions, including those developed through work funded partly by federal grants.

This model gave rise to a division of labor so familiar today that few people realize how remarkable an innovation it was at the time. University scientists generally specialize in basic science – exploring the structures of the physical, chemical, and biological world – and sometimes develop product prototypes. Private sector firms, meanwhile, license these ideas and bring commercial products based on them to market. Today, university scientists in the United States conduct approximately half of all basic (as opposed to applied) research, with a majority of it funded by federal grants. Business R&D often depends on this research. One study by leading intellectual property experts showed that more than 73% of papers cited in private sector patents during a period in the 1990s originated from research at universities. Innovation is becoming even more dependent on university research today as private industry’s engagement with basic science recedes due to the decline of once-great research centers like Bell Labs and Xerox Park.

America’s postwar R&D model has been a resounding success. According to one global ranking, U.S. universities constitute 46 of the top 100 research institutions in the world and eight of the top 10 for the quality of their patenting activity. U.S.-based scientists account for 30% of citations in top-tier scientific journals, according to 2022 data from the NSF. That compares with 20% for Chinese researchers and 21% for all of Europe.

Read the rest of this piece at BushCenter.org.

J.H. Cullum Clark is Director, Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative and an Adjunct Professor of Economics at SMU. Within the Economic Growth Initiative, he leads the Bush Institute's work on domestic economic policy and economic growth. Before joining the Bush Institute and SMU, Clark worked in the investment industry for 25 years.

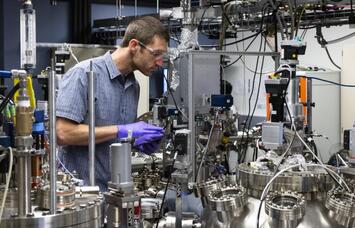

Photo: Researchers working to develop superconducting materials for quantum computing, Oak Ridge national Laboratory via Flickr, under CC 2.0 License.

The China Problem

When I founded Land Innovation, a Civil Engineering and Land Surveying application company in the late 1970's collaborating with Hewlett Packard, in the mid to late 1980's I explored having a distribution arm in China. I was told I'd have to have a China 'partner' and share my intellectual property. I thought what American company with a unique edge would even remotely consider partnering with a Chinese entity and just handing them over any advantage would be a good idea. Decades later, look at today's situation. We just handed over to them, actually gifted them, the advantages we used to have just to get cheap products. Here in Minneapolis in 2012, I saw this incredible product (I'll not name them) which was a programmable sprinkler head that can do any shape just by pressing a button on a smart phone to define area. It was 4X more expensive than a normal head, but you would need 1/4th of them with less conduit and save 50% on the water bill. What could possibly go wrong with this next billion dollar product? There were bugs to be worked out as the prototypes were not working right. So I asked why not go with a different supplier? The China based company that developed the prototypes demanded 50% ownership (I was told) to create the product. Once you hand over the foundation of an innovative product or idea (nationally) you lose something. That said, as a father-son hobby business we make custom engine covers for the C8 Corvette mostly to get the experience of developing a 'physical' product (CustomCre8ions(dot)com). The China supplier was 1/4th the cost of going to Mexico (which was a ton cheaper than a US manufacturer). We had no clue as to the quality of the product that we sent over by digitally scanning a manmade prototype. The products were on time and on budget and extremely well made with high-temp plastic. This is essentially a 'dumb' product meaning while patent pending, anyone could easily replicate it and not the source of our income. Had we actually had something of intellectual value I'd rather spend more not to hand over to a Chinese manufacturer. While this does not exactly address the article I thought it is somewhat of a larger problem as we are losing a competitive advantage as a nation of (past) innovation.