Both the world and the nation remain in the midst of the greatest economic downturn since the Great Depression. But with all the talk of “green shoots” and a recovery housing market, we may in fact be about to witness another devastating bubble.

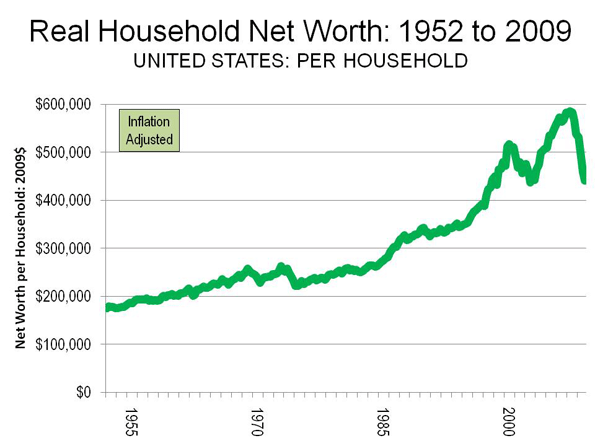

As we well know, the Great Recession was set off the by the bursting of the housing bubble in the United States. The results have been devastating. The value of the US housing stock has fallen 9 quarters in a row, which compares to the previous modern record of one (Note). This decline has been a driving force in a 25 percent or a $145,000 average decline (inflation adjusted) in net worth per household in less than two years (Figure 1). The Great Recession has fallen particularly hard on middle-income households, through the erosion of both house prices and pension fund values.

This is no surprise. The International Monetary Fund has noted that deeper economic downturns occur when they are accompanied by a housing bust. This reality is not going to change quickly.

How did the supposedly plugged-in economists and traders in the international economic community fail to recognize the housing bubble or its danger to the world economy? It is this failure that led Queen Elizabeth II to ask the London School of Economics (LSE) “why did noboby notice it?”. Eight long months later, the answer came in the form of a letter signed by Tim Besley, a member of the Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England (the central bank of the United Kingdom) and Professor Peter Hennessey on behalf of the British Academy.

The letter indicated that some had noticed what was going on,

But against those who warned, most were convinced that banks knew what they were doing. They believed that the financial wizards had found new and clever ways of managing risks. Indeed, some claimed to have so dispersed them through an array of novel financial instruments that they had virtually removed them. It is difficult to recall a greater example of wishful thinking combined with hubris.

The letter concluded noting that the British Academy was hosting seminars to examine the “Never Again” question.

Among those that noticed were the Bank of International Settlements (the central bank of central banks) in Basle, which raised the potential of an international financial crisis to be set off by a bursting of the US housing bubble. Others, like Alan Greenspan, noticed, telling a Congressional Committee that “there was some froth” in local markets. Others, across the political spectrum, like Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman, Thomas Sowell and former Reserve Bank of New Zealand Governor Donald Brash both noticed and understood.

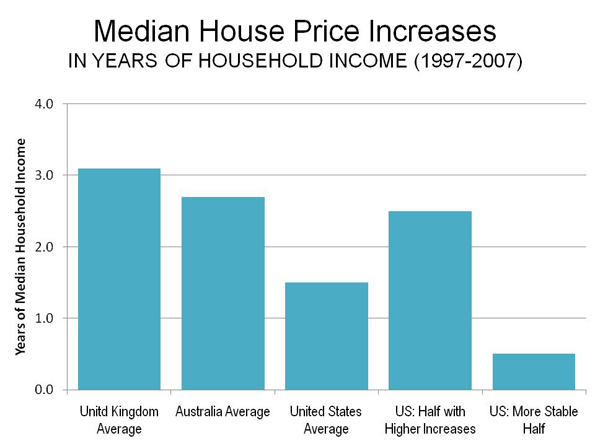

Missing the Housing Market Fundamentals: The housing market fundamentals were clear. With more liberal credit, the demand for owned housing increased markedly, virtually everywhere. In all markets of the United Kingdom and Australia, house prices rose so much that the historic relationship with household incomes was shattered. The same was true in some US markets, but not others (Figure 2).

On average, major housing markets in the United Kingdom experienced median house prices that increased the equivalent of three years of median household income in just 10 years (to 2007). The increases were pervasive; no major market experienced increases less than 2.5 years of income, while in the London area, prices rose by 4 years of household income. In Australia, house prices increased the equivalent of 3.3 years of income. Like the UK, the increases were pervasive. All major markets had increases more than double household incomes.

Based upon national averages, the inflating bubble appears to have been similar, though a bit more muted in the United States, with an average house price increase equal to 1.5 years of household income. But the United States was a two-speed market, one-half of which experienced significant house price increases and the other half which did not. In the price escalating half, house prices increased an average of 2.4 times incomes. The largest increases occurred in Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego, where house prices rose the equivalent of 5 years income. In the other half of the market, house prices remained within or near historic norms relative to incomes. A similar contrast is evident in Canadian markets. In some, house prices reached stratospheric and unprecedented highs, while in others, historic norms were maintained.

Underlying Demand: Greater Where Prices Rose Less: The difference between the two halves of the market was not underlying demand. Overall, the half of the markets with more stable house prices indicated higher underlying demand than the half with greater price escalation. Overall, the housing markets with higher cost escalation lost more than 2.5 million domestic migrants from 2000 to 2007, while the more stable markets gained more than 1,000,000 (Calculated from US Bureau of the Census data).

The Difference: Land Use Regulation: The primary reason for the differing house price increases in US markets was land use regulation, points that have been made by Krugman and Sowell. This is consistent with a policy analysis by the Dallas Federal Reserve Bank, which indicated that the higher demand from more liberal credit could either manifest itself either in house price increases or in construction of new housing. Virtually all of the markets with the largest housing bubbles had more restrictive land use regulation.

These regulations, such as urban growth boundaries, building moratoria and other measures that ration land and raise its price collaborated to make it impossible for such markets to accommodate the increased demand without experiencing huge price increases (these strategies are often referred to as “smart growth”). In the other markets, less restrictive land use regulations allowed building new housing on competitively priced land and kept house prices under control. The resulting price distortions leads to greater speculation, as has been shown by economists Edward Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko.

A Wheel Disengaged from the Rudder: The normal policy response of interest rate revisions had little potential impact on the price escalating half of the housing market, because of the impact of restrictive state, metropolitan and local housing regulations. These regulations materially prohibited building on perfectly suitable land and thus drove the price up on land where building was permitted. So, while Greenspan and the Fed saw the “froth” in local markets, they missed its cause. The British Academy letter to the Queen is similarly near-sighted. Restrictive land use regulation has left central bankers in a position like a ship’s captain trying to steer a massive vessel with a wheel that is no longer connected to the rudder

The Bubble Bursts: When teaser mortgage rates expired and other interest rates reset, a flood of foreclosures occurred, which led to house price declines that negated much of the housing bubble price increases in the United States. The most significant of these took place in restrictive markets, especially in California and Florida. By September of 2008, the average house had lost nearly $100,000 of its value in the more restrictively regulated half of the market, and averaged $175,000 in these “ground zero” markets. These losses were unprecedented and far beyond the ability of mortgage holders to sustain. This led to “Meltdown Monday,” when Lehman Brothers collapsed and the Great Recession ensued.

By comparison, the losses in the more stable half of the market were modest, averaging approximately one-tenth that of the price escalating half.

Can We Avoid Another Bubble? The experience of the Great Recession underscores the importance of having a Fed and other central banks that not only pay attention, but also understand. This requires “getting their hands dirty” by looking beyond macro-economic aggregates and national averages.

This does not require an increasing of authority of the Federal Reserve or other central banks. As Donald L. Luskin suggested in The Wall Street Journal, we “don’t want the Fed controlling asset prices.” All we really need is for the Fed and other central banks to notice and understand what is going on, not only in housing, but in other markets as well.

A public that depends upon central banks to minimize the effect of downturns deserves institutions that are not only paying attention, but also understand what is driving the market. The Fed should use its bully pulpit, both privately and publicly, to warn state and local governments of the peril to which their regulatory policies imperil the economy.

There are strong indications that future housing bubbles could be in the offing. Not more than a year ago, the state of California enacted even stronger land use legislation (Senate Bill 375), which can only heighten the potential for another California-led housing bust in the years to come, while reducing housing affordability in the short run. There is a strong push by interest groups in Washington to go even further (see the Moving Cooler report), making it nearly impossible for housing to be built on most urban fringe land. This is a prescription for another bubble, this time one that would include the entire country, not just parts of it.

Note: Quarterly data has been available since 1952 from the Federal Reserve Board Flow of Funds accounts

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

Britain's bubble economy

That is a very intelligent comment from Ian Abley regarding the situation in the UK. I am sure that the voting public really do not understand the issues at all intelligently, thanks to appallingly bad media analysis or total lack thereof. The situation is the same "down under".

Way back in June 2005, Fred Harrison essayed on "The Mystery of Britain's Missing Recession", in which he got everything right, except that he utterly missed the role of land rationing. If you want to understand the mechanisms that Ian Abley touches on, of how inflated house prices "stimulate" an economy, this is a "must-read".

http://www.dailyreckoning.co.uk/economic-forecasts/the-mystery-of-britai...

Here are some excerpts. Bear in mind he is writing this in June 2005:

"How did Britain avoid the 2001 recession that ensnared other countries? Recessions followed after each of the post-war periods when real house prices rose above the level of real household disposable income - in 1972, 1979 and 1987.

Britain's manufacturers did suffer a recession. Total output of the economy rose by over 5% from the end of 2000 to the end of 2003, but manufacturers had a different story to tell. They suffered a fall in output of over 5% in that period. The 6.7% rate of return on their capital (2001) was the lowest since the trough of the recession nine years earlier, in 1992.

So how did Gordon Brown guide Britain through the global turbulence of these years to avoid the embarrassment of a formal recession for the whole economy?......

".......The clues are to be found in the financial sector. Gordon Brown sponsored a classic Keynesian pump-priming operation. This time, however, there was one peculiar difference. Instead of accepting responsibility for managing the economy, he shifted the burden on to ordinary families.......

".......Instead of increasing taxes and/or public debt, to finance investment in infrastructure - to create jobs and sustain growth - he presided over the growth of a record level of personal indebtedness. By July 2004 that debt reached a staggering £1 trillion. To underpin this indebtedness, a blind eye had to be turned to inflation in the housing market.

If the business cycle had played out in the way that we would have predicted on the basis of historical trends, the price of houses would have deflated in 2001-2. This would have been the outcome of a mid-cycle recession. Instead, under Gordon Brown's stewardship, the residential sector was allowed to bubble. This set new benchmarks for prices: the next housing bubble would have to inflate to stupendous levels before finally collapsing and driving the economy into the Depression of 2010.

But in the meantime, Britain's consumers were on a spending spree. They borrowed like there was no tomorrow to finance the purchase of luxury goods, holidays in exotic locations, new cars, and improvements to their homes. Following the election of New Labour in 1997, consumption grew faster than output, with retailers sucking in imported goods to make up the difference. Between 1999 and 2001, consumption grew exactly twice as fast as Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Unsecured consumer debt rose at an annual average rate of nearly 11% over the five years to 2004. While Gordon Brown preened himself with declarations about his virtuous 'prudence' in handling the nation's public finances, he sanctioned private bingeing that undermined the culture of thrift. Britain's consumers would Spend, Spend, Spend the economy out of the recession before anyone noticed! They spent more on their credit cards than the rest of Europe put together. By 2003 those credit cards were loaded with a debt of £120bn. Shoppers in the other 14 nations of the European Union (EU) spent just £45bn between them.

The financial and psychological key to the spending spree was an out-of-control housing market. With every percentage increase in the capital gain on their homes, owners felt wealthier if not wiser. They withdrew equity at record rates so that they could buy the luxury goods that created the trade imbalance between Britain and the rest of the world. They also borrowed more to 'trade up' to more valuable properties - the home-owner's way of speculating in the capital gains of the future......"

Do read the whole thing.........

Vitally important subject, this.

Wendell,

Keep up this very good work. This argument has been my main cause on the net for some time now. The following is the arguments I have worked up to recently.

The following are valuable papers from certain researchers, that argue that property price bubbles are caused mostly by government imposed land rationing policies.

Wendell Cox and Ronald Utt: “Don’t Regulate the Suburbs: America Needs a Housing Poliicy that Works”.

http://www.heritage.org/Research/SmartGrowth/bg2247.cfm

Alan Moran: “The Tragedy of Planning: Losing the Great Australian Dream".

http://www.ipa.org.au/library/MORANPlanning2006.pdf

Those who insist that factors other than land use rationing, such as taxation treatment of housing, are responsible, should look at page 54 onwards, (page 61 of the PDF) where Moran gives analysis charts of these factors across a number of countries that have experienced housing bubbles.

Oliver Marc Hartwich and Alan Evans: “Unaffordable Housing: Fables and Myths”

http://www.policyexchange.org.uk/images/publications/pdfs/pub_38_-_full_...

On page 17 is a graph of previous house price bubbles in the UK . The UK just happens to have had land use rationing decades ahead of everyone else. They have also had house price bubbles decades ahead of everyone else; they just never got the connection.

Oliver Marc Hartwich and Alan Evans: “Bigger Better Faster More: Why Some Countries Plan Better Than Others”

http://www.policyexchange.org.uk/images/publications/pdfs/pub_39_-_full_...

Germany has policies of funding local government which are powerful incentives to development and construction. Consequently, Germany has not had a house price bubble other than in a few locales where local anti-development sentiment was strong enough to survive the cost impact of consequent loss of funding. They have had a nationwide 1990’s construction boom and subsequent depressed property prices which are frequently misinterpreted as a “bubble”. They do not, however, have huge increases in household debt backed by the “faery gold” of house price inflation, and subsequent wipeout of equity bringing the whole banking and finance system down. Germany can honestly say that the impact on their economy is spillover from outside their borders. Just about no other country can say that, including NZ and Australia.

I badly wish for more evidence than this, but this is pretty conclusive to my mind.

Why property price bubbles, nearly everywhere, at this time? There have been numerous periods of monetary looseness in the past which have led to bubbles in the share market. I would argue that every potential property price bubble in the past was avoided in time by construction booms, other than in the UK , obviously. (There is a difference between house construction booms and house price bubbles that is being confused by many commenters today). But the 1980’s and 1990’s were marked by the advancement of environmentalism and urban limits and planning and land use rationing. Just as environmentalist mismanagement of forestry policy has finally had to be blamed for unprecendentedly destructive forest fires in California and Australia , I think it is high time that the true blame for the housing bubble crises was directed that way also.

There are only a few developed countries today that have not had house price bubbles: these include Canada, Austria, the Czech Republic, and Germany. Pro-development policies seem to be central to these countries successful avoidance of these bubbles. Contrast the UK; since their Town and Country Planning law of 1947, they have had no less than four of the world's historically worst house price bubbles, including the current one. One wonders whether, now that these issues have become equally consequential for so many other countries as well, the penny will drop at last.

The English economist Fred Harrison has written copiously on the phenomenon of business cycles dominated by house price bubbles, using the UK experience to develop his theories. He has been credited with correctly predicting the latest one. Yet even he seems to have missed the point that these bubbles were unique to the UK until such time as other countries instituted similar land rationing policies.

In many countries, opportunist politicians and media are using the crisis in the USA as a scapegoat for what are actually domestically created troubles, for which the mechanism is identical to that of California - regulatory land rationing followed by a house price bubble, which monetary policy, taxation, and finance law becomes increasingly impotent to control. Ireland and Spain are among the worst cases, along with the UK. Hugh Pavletich, one of the authors of the Demographia survey, has been pointing to the Gold Coast of Australia, now the least affordable housing market in their survey, as the next California in the making, with potentially disastrous consequences for the Australian economy.

Time will tell whether more attention should have been paid to this issue sooner. If the land supply issues are not resolved, we can expect these massively destructive bubbles to become regular cyclical economic fixtures just as share market bubbles have been for a long time but without the same destructive effects. House price bubbles are much more destructive precisely because they affect almost everyone, they involve much greater sums of money, and very much greater assumption of household debt, whether for purchase of a home or for collateral-based spending.

A lot of analytical literature fails to distinguish between house price bubbles, and house construction bubbles. The latter has happened regularly before, but the current bubble in house prices is a different and altogether much more damaging phenomenon. A bubble that is an oversupply of new homes actually keeps prices low throughout, and brings about its own demise as customers fail to materialize. A house price bubble, though, absent a supply vent, is self-perpetuating right up to the point at which it brings about collapse of the whole economy. "Land banking" and similar capture of available land by investors, can and has resulted in price bubbles even in the face of authorities releasing "enough" land for population increase based demand. It would seem that either a totally free supply in land, or "performance based planning" as Hugh Pavletich aptly describes it, based on actual prices, not bureaucratic calculations of supply requirements, is necessary to avoid this phenomenon in future.

The following are specific comments about Australia and New Zealand, who have serious house price bubbles that have not yet burst. The IMF has noted this with concern in a recent report:

http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,25906781-5013404,00.h...

Regarding the USA as an aggregate "housing market" results in much lower percentages for house price inflation and mortgage debt than for Australia and New Zealand. What the USA experience illustrates is how an "outlier" region, in that case California, can damage a whole economy. A nationwide median multiplier for house prices of 4.4 or so, is not an economy-breaker, but a significant region blowing out to 9 or more evidently is.

It looks as though Queensland is going to be Australia's California. New Zealand, though, seems to be lucky enough to not yet have such a significant outlier. The entire country might reach implosion level though.

"The Inoculated Investor" is right that Australia and NZ are merely trailing the US experience by a few years.

http://seekingalpha.com/article/146889-analysis-of-australian-bank-funda...

The crucial thing is Reserve Bank Base Interest Rates; there is still significant room for cuts. However, all this will do is keep these housing bubbles inflated for a final disastrous implosion like in California.

The quality of analysis out in Australia and NZ is just ridiculous. Rising house prices are regarded as a cause for celebration, a sign of economic recovery. Excuse me? With rising unemployment, economy slowing down, or in NZ's case, in prolonged recession already? Do people never learn, even with overseas experience to go by?

Australia and NZ have developed serious housing bubbles in spite of relatively HIGH interest rates, approximately double those of the USA. This evidence would tend to indicate that Greenspan is not as much to blame for the USA situation as many people think. The fact that Australia and NZ have not had any equivalent of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae is significant also. But government handouts now, to first home buyers and the like, will not help in the long run, not to mention the Australian government's guarantees of their main trading banks debt, which is resulting in investment flows into Australia that are ending up in yet more mortgage finance rather than productive business. This is because the underlying problem in housing is one of inflexibilities having been imposed on supply, and these inflexibilities still exist.

Investor speculation in property is a significant factor, combined with the inflexibility of supply. An attitude develops, that house prices cannot fall, and will always rise. This is the same phenomenon as share market speculators; "the greater sucker" gambit. But land supply used to exercise a limit on house (land) price appreciation; the result of excess demand was "oversupply", or as the Austrian economists call it, "malinvestment"; as supply almost inevitably "overshot" demand. The economic shaking down that followed these housing oversupply booms was never any more than a fraction more damaging than a house price bubble unrestrained by supply has proved to be.

Even if the authorities involved claim to be allowing "enough" development and supply of new homes, the existence of a rationing process has allowed the supply process to long since have been captured by speculators, in the form of "land banks". California and Australia and New Zealand are marked by quantities of houses that have been bought purely as speculation, and the excess number of such houses has temporarily kept a downwards pressure on rental prices; as there are simply more unoccupied speculator-owned homes than there are renters.

So we have several confusing factors that are lost sight of in "aggregating" nationwide housing markets. There are localised price bubbles where undersupply is clearly responsible, yet in some places there is actually a combination of oversupply AND unaffordable prices, contrary to all laws of economics. The only explanation is the capture of the supply rationing process by speculators.

The lack of supply factors to keep prices low, means that speculators can achieve "greater sucker" gains right up to the point at which high house prices actually kill the whole economy. Nothing else will prevent these bubbles, except addressing the supply issue. Capital Gains taxes, short of 100% or close to it, will merely be "costed in" by speculators. Central Bank interest rates would have to be so high, to defeat the gains available under an inflating property bubble situation, that productive businesses would collapse long before the property bubble could be deflated.

The people who are caught in the middle, are first home buyers. These people have been utterly betrayed by the market experts; they will be wiped out undeservedly. The young actually should be getting informed on these issues and lobbying government to address the affordability issue through land supply, not handouts or assistance that simply serve to help the bubble grow.

Boundaries and Values

I omitted from the above essay, a specific comment about the quantifiable differences in values of land within urban limits compared to outside them.

Alan Moran, in "The Tragedy of Planning" (linked to above) discusses this phenomenon. Land for agriculture has a market value. In markets where there are no land rationing policies regarding housing development, there is very little difference in the values of raw land for agriculture, and land that is put into development for housing. The resulting urban fringe sections, once developed, sell for a price that calculates to the raw land value, plus cost of development, plus a reasonable profit.

Where there are urban limits, though, this relationship is broken. Urban fringe sections selling prices, less cost of development, comes to many times the value of comparable agricultural land.

MOTU Economic Research in New Zealand, did a study of this phenomenon in Auckland, that concluded that the land inside the urban limit was driven up by 7 to 13 times in value, compared to the agricultural land immediately outside the limit. What is more, they argue, without attempting to quantify it, that even the land outside the urban limit has been forced up by long-term expectations that it will one day be rezoned.

Alan Moran states that there are markets where the land values have been driven up many times more than the MOTU study results.

Some people might tend to jump in and blame "speculators" for capturing all the available land within urban limits and then making "obscene profits" out of it. This is unfair. The regulators have created a situation where the most decent developers will simply quit the market - Hugh Pavletich in New Zealand is one such example. Developers are simply forced to play "dog eat dog", and get land before their rivals do; and then carry the finance costs of holding it until such time as demand results in development proceeding.

Many such developers have now gone bankrupt, and finance companies have been brought down in their wake. Yet the land involved in these cases stubbornly refuses to resume levels that bear any relationship at all to comparable agricultural land, even in the face of recession and rising unemployment and a dearth of potential new home buyers. This is a sure sign that powerful economic distortions are at work.

This is not to ignore the fact that relative location affects land values powerfully. Of course land located closer to the urban centre will be several times more expensive than fringe land. But when the fringe land is inflated in value, the land closer to the urban centre is inflated by a related factor. This is why old homes that are actually worth nothing as a structure, still cost first home buyers hundreds of thousands of dollars in markets with regulated land use, yet in markets without, these homes tend to be even cheaper than the already affordable fringe homes.

Alain Bertaud, in "The Costs of Utopia" actually analyses why urban limits, where they have been in use the longest, such as in Portland, have actually driven up the average commute lengths because the pattern of higher density development has been distorted. Traditionally, higher density development took place on the more valuable land closer to a city centre - Bertaud shows several graphs of cities where the population density "profile" is normal: highest in the centre and gradually reducing out to the fringes.

But in Portland, the land has been forced up so high in price that anyone who might want to live at higher densities simply cannot afford the prices that "inner area" high density homes end up having to sell for. The result, aided by first home buyers desperately seeking the "least unaffordable" option, is that the higher density development is taking place at the urban fringes! Look at the graph on page 12:

http://alain-bertaud.com/images/AB_The%20Costs%20of%20Utopia_BJM4b.pdf

In other words, even the necessity for which urban limits are claimed to be needed, is being defeated rather than served by them. Yet another example of "unintended consequences" and "fatal conceits".

In Britain the next housing bubble has already started

Wendell

The British government and their loyal opposition have worked incredibly hard to ensure that another housing bubble was achieved by 2010. In fact the earliest signs of that financially re-engineered house price inflation is already evident in the most inflated markets of London and the South East. Nationally, on average, house prices are on the rise. This is no accident or over-sight. It is deliberate.

Without house price inflation in Britain our economy is dead. The City of London circulates £1.2 trillion of mortgage finance through the trade in Britain's existing housing stock. That stock is a reasonably secure investment, even though it is physically ageing.

Everyone here knows that Britain is giving up on building new homes, but no-one really objects. This year only 100,000 homes will be built. In 2007 at the height of the last housing bubble only 200,000 were built. Gordon Brown insisted up to 2007 that 240,000 new households were forming every year, needing housing. His advisers now tell him that 290,000 households are wanting a home of their own.

The demographic demand is not being met, and has not for decades. In 1968 Britain's house building peaked at 413,000 when government required 500,000 to be built. Production has been in decline since then, as house price inflation became more economically important than ensuring every new household had a new home. The financialisation of British housing started in the early 1970s with the "Barber boom", was extended in the 1980s with the "Thatcher boom", and has lost touch, as you say, with household income in the "Brown bubble" of 1997 to 2007. New Labour has found house price inflation to be an excellent lubricant for our tired economy. Gordon Brown will be welcoming the start of another bubble, though he will publicly cry about the social effects of "unaffordability" and overcrowding.

Britain's housing production is not going to recover. This is a disaster for the construction industry, and for society. The planning system is being strengthened by New Labour in power to frustrate volume house building. Demographic demand will be ineffective.

The Conservatives in opposition are planning even more restrictive planning policies in their "new localism" agenda. This is encouragement, if any were needed, for those already occupying housing as a financial asset to oppose the utility of new house building. The Conservatives are not guaranteed an election win. far from it in my view. Having enjoyed the last "Brown bubble" many here will reward Gordon Brown for starting another one come the election.

The British housing market is set for another, much more dramatic and volatile speculative bubble. This is not irrational. It is popular in an economy where wages are so low, and housing investments substitute for pensions. The bubble making is deliberate, and the economists that grovel to the Queen know that property speculation is exactly the business that the home owning middle classes and the aristocracy both enjoy.

The only way to stop this second "Brown bubble" happening is to abolish the 1947 planning legislation that makes it illegal for working people to buy a plot of redundant farmland and build a house. Even if this were possible the difficulty is that in doing so - releasing for development just some of the 90% of Britain that is not built on - the finacialised British economy based in the City would collapse. The other difficulty is of course social. While the lower middle and working classes could build homes, organised socially, for themselves, they don't have the capital to do it.

So we're in a political and economic predicament. One that will tend to be ignored as the next bubble inflates. The task now, as that process of house price inflation recommences, is to point out that a political class in Britain is running the planning system to the benefit of financiers in the City. They do that because since the 1970s in particular they have failed to make their profits from investment in British industry. They have a lot of surplus to lend, and lending on a constrained supply of housing is a low risk percentage return. The borrowing and trading can carry on successfully without any new housing being built.

British planners effectively work for the Treasury. British households, trying to augment low wages and inadequate pensions, demand house price inflation. The political demand is not (yet) for household growth to be met with new house building.

Ian Abley

www.audacity.org