The prelude to my round trip by train across the Gobi Desert from Lanzhou (Gansu) to Urumqi (Xinjiang) was a trip from Hong Kong to Lanzhou. This article includes photos from that trip, and some from previous trips, as noted on the figures. The travel highlight was a 10.5 hour and 2,700 kilometer (1,700 mile) train trip from Guangzhou to Lanzhou, through southern and central China, then turning west along the Yellow River. It was all daylight until the train entered more than 100 miles of tunnels on the final approach to Lanzhou.

The Pearl River Delta

The trip started on the MTR urban rail line from Hung Hom Station in Kowloon, Hong Kong (Figure 1). Hong Kong now has an urban area population of nearly 7.5 million, about a million more than Dallas-Fort Worth or Toronto. Figure 1 shows the International Finance Centre, which at 484 meters (1,588 feet) and 108 floors is the 10th tallest building in the world. The International Finance Center is located across Hong Kong Harbor, in Kowloon, on the mainland, rather than on Hong Kong Island, where the tallest buildings traditionally have been located.

The MTR trip ended at the Futian Border Crossing between Hong Kong and Shenzhen. Travelers use a weather protected walkway across the Shenzhen River. The Shenzhen urban area had a population of less than 100,000 in 1980, which has grown to 13 million, and is now the 26th largest in the world. It is about the population of Tehran or Istanbul. Figure 2 shows the Futian CBD (central business district), with the Ping An Finance Center, which is the 4th tallest building in the world, at 599 meters (1,965 feet) and 115 floors.

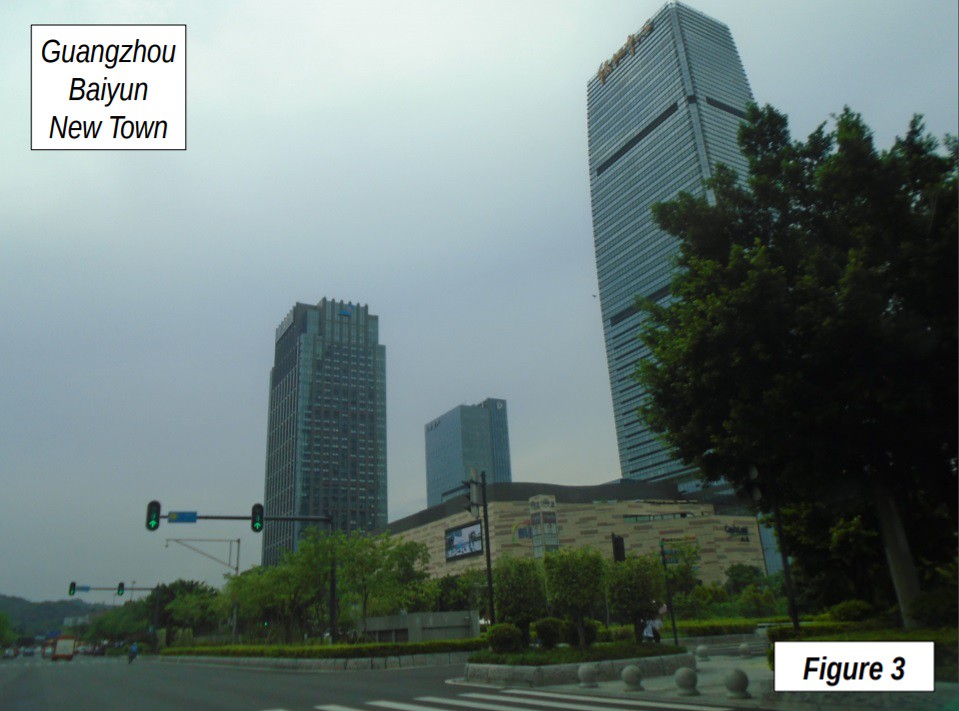

After visiting Shenzhen, the next leg of the trip was a quick, 55 minute ride from Futian Station to Guangzhou South Station. Guangzhou South is emerging as the key rail hub in the Pearl River Delta with travel times of one hour or less with service now or soon available from all cities, including Hong Kong and Macao. The top photograph is of the Zhujiang New Town, Gaungzhou’s new CBD, taken on a stormy night from Canton Tower (second tallest free-standing television tower in the world), at 604 meters or 1,982 feet). Zhujiang has been constructed in the last decade. It includes the 7th tallest building in the world, the CTF Finance Centre, at 530 meters, nearly as tall as New York’s World Trade Center. It also includes the 17th tallest, the International Finance Centre, at around the height of the Willis (former Sears) Tower in Chicago, just east across the central axis. Figure 4 is Baiyun New Town, the redeveloped former international airport. The new Baiyun International Airport is located about 24 kilometers (15 miles) north, but still within the urban area.

The New Fuxing Train

After a few days in Guangzhou I boarded train G72 for Lanzhou, which departed at 8:55 a.m. The trainset was the new “Fuxing” Series, (Figure 4) which has a 400 kilometers per hour (kph) or 249 miles per hour (mph) top operating speed, and will run at 350 mph (217 kph) on many trips throughout China starting in September. The top speed on this trip was approximately 310 kph (193 mph). There were only five intermediate stops, making the average trip segment nearly 450 kilometers (275 miles), and a very fast average speed of more than 255 kph, or nearly 160 miles mph. The Guangzhou to Xi’an segment, with only three intermediate stops was even faster, at 279 kph (173 mph). By comparison, a later high-speed, similar length rail trip from Lanzhou to Shanghai had 19 intermediate stops and averaged only 190 kph (115 mph).

Guangzhou to Zhengzhou

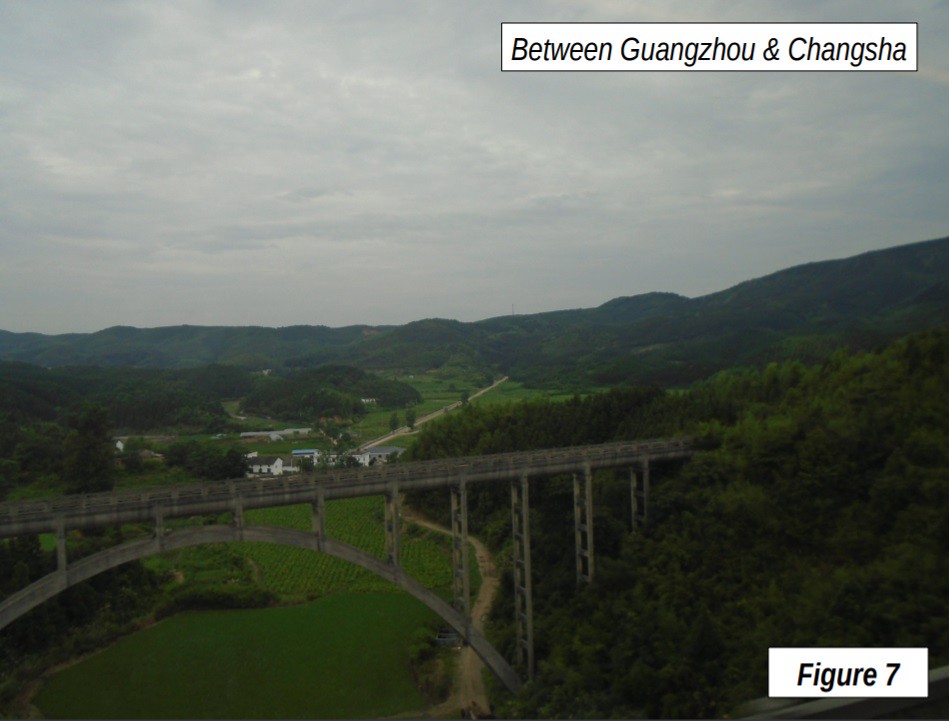

The first part of the trip was through the Guangzhou-Foshan urban area, the core of the Greater Bay Area, the largest continuous extent of urbanization in the world, with nearly 55 million people. But, it’s not long until the greenery of rural south China dominates the scenery. (Figures 5-8).

The first stop was Changsha (11:12 a.m.), the capital of Hunan province, with an urban area population of 4 million (about the size of Berlin, Sydney or Seattle). Changsha sits astride the Xiang River, a tributary of the Yangtze. Figure 9 shows development in the old core, with IFS Tower I in the distance in the new central business district along the river, approximately 3 kilometers (2 miles) to the west, The IFS Tower is the 11th tallest in the world, at 94 floors and 452 meters (1,483 feet). This equals the height of the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, the tallest in the world from 1998 to 2004. Changsha was to be the home of the world’s tallest building, a prefabricated structure to be built in 90 days that would have reached 220 floors. The project has now been cancelled due to environmental concerns.

Changsha has had particularly intense urban expansion and development for its size. Figure 10 is a major residential condominium construction project, which now has more than 100 towers, many over 30 floors. Xiangtan, birthplace of Chairman Mao Zedong borders on Changsha. Beyond Changsha, the country is a bit less hilly, but every bit as green (Figures 11 & 12).

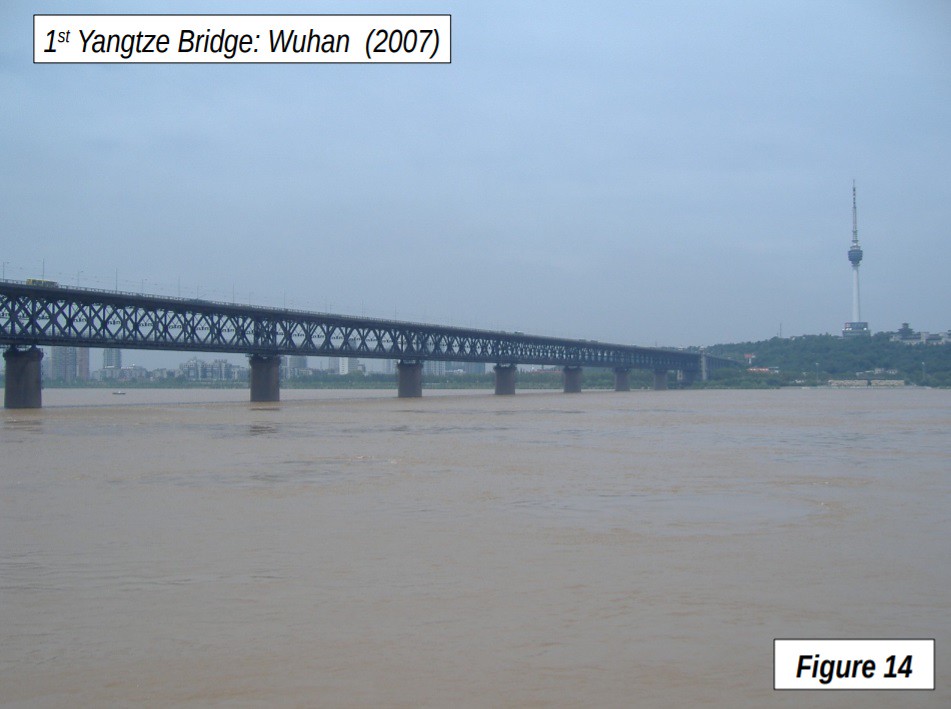

The next stop was Wuhan (12:33 p.m.), sometimes called the Chicago of China, due to its heavy industry. Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province and China’s 10th largest urban area, has slightly fewer residents than Chicago, which has 9 million. Wuhan was amalgamated in 1927 from the cities of Hankou, Wuchang and Hanyang. The city is nearly split in half by the Yangtze River which averages about 1.6 km. wide (1 mile). By comparison, the Hudson River adjacent to lower Manhattan in New York is about 1.3 km. wide. The CBD is shown in the distance in Figure 13, 14 km from Wuhan North Station (9 miles), on the other side of the Yangtze. It includes the new Wuhan Center Tower, which, when complete, will be 438 meters tall (1,437 feet), 88 floors and among the 20 tallest in the world.

The first bridge permanent crossing of the Yangtze was opened here in 1957 (Figure 14). Now, according to China Daily, there are more than 160 bridges and tunnels cross the Yangtze. As the train leaves Wuhan, the rural greenery starts again and dominates the scenery north of Wuhan (Figure 15).

Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan is the next stop, at 2:33 pm, and is just south of the Yellow River. Zhengzhou has an urban area population of 7 million, similar in size to the Essen (Rhine-Ruhr) urban area, Dallas-Fort Worth or Toronto. The G4 Expressway, which runs from Hong Kong to Beijing is shown in Figure 16, just south of Zhengzhou. The photograph also shows the Chinese expressway network “shield” similar to the US “interstate” highway shield. Zhengzhou’s “new” CBD (central business district) was labeled as a “ghost city” by the Daily Mail, a characterization I disputed as premature from visiting the site. Forbes writer Wade Shepard noted that this is a general tendency with respect to the new developments in China, noting that “We're are all too often too quick to criticize new cities and shower them with proclamations of doom, we are all too often too quick at the trigger.” (Figure 17) The wide arterial streets of Zhengzhou, typical of Chinese post 1980 development are shown in Figure 18.

Zhengzhou to Xi’an

At Zhengzhou, the train turns west, following the route toward Xi’an, generally to the south of the Yellow River and north of the Qinling Mountains. Figure 19 shows agricultural country between Zhengzhou and Luoyang, which served as an ancient capital of China. The Qinling Mountains, spectacular though not very lofty in this area, resemble the Alps in their contour (Figures 20-22). The rail line does not cross the Yellow River, which turns 90 degrees north toward Inner Mongolia, forming the Ordos Loop. The Yellow River rejoins the rail line at the end of the trip (Lanzhou).

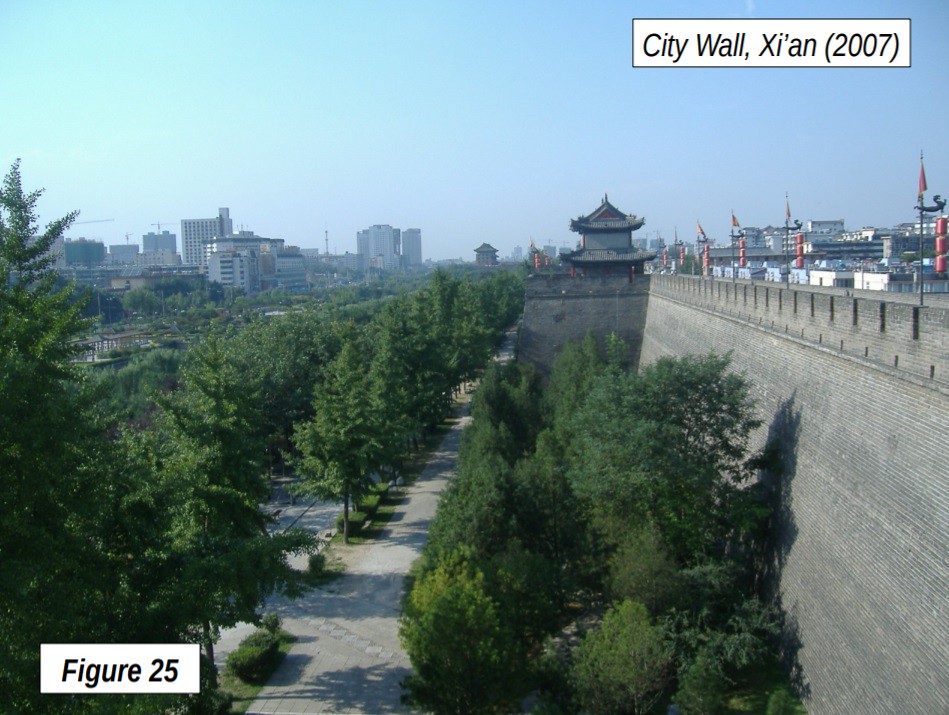

Xi’an, perhaps the most famous of China’s ancient capitals (then called Chang’an) is reached at 4:31 p.m. Xi’an has an urban area population of over 6 million, about the size of Miami or Philadelphia. The capital of the province of Shaanxi (Figures 23-24), Xi'an sits on the Wei River, a tributary of the Yellow. The city wall, which dates to the 14th century but has been rebuilt through the intervening centuries, is an important historical attraction (Figure 25). The museum of the terra cotta warriors is close by.

Xi’an to Lanzhou

The train slows down after Xi’an, where speeds are limited, at least for now, to 250 kph. Agricultural and mountainous country resumes after Xi’an (Figures 26-28). Tianshui, reached at 6:06 p.m., is by far the smallest urban area (400,000) with a stop (Figure 29). Shortly after this point the mountains begin to climb (Figures 30-33), a significant barrier, leading to the fact that much of the rest of the trip is in tunnels. At one point west of Tianshui, there was a station in a tunnel (not served by this train), which residents would have to reach by elevators and/or stairs.

The train arrived at the final stop, Lanzhou at 7:24 p.m. Lanzhou (Figures 34-35) is the capital of the province of Gansu, with an urban area population of 3 million (about the size of San Diego or Minneapolis-St. Paul). Lanzhou is also the home of one of China’s most famous dishes, Lanzhou noodles (this video shows how they are made in Lanzhou).

It was a very interesting trip, from the world’s largest collection of adjacent urban areas through the greenery of south and central China and then westward along the Yellow River, all with more than its share of the world’s tallest man-made structures. Anyone who wishes to see where cities are headed in the 21st Century needs to come to China.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photograph: Zhujiang CBD, Guangzhou, by author. All photographs by author.

Chinese cities

Chinese cities--both from your pictures and from my limited experience--seem remarkably ugly. The countryside, on the other hands, looks spectacular.

The article would be much easier to read if the pictures were embedded in the text.